Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Mumbai ka King Kaun? Bhiku Mhatre!!!

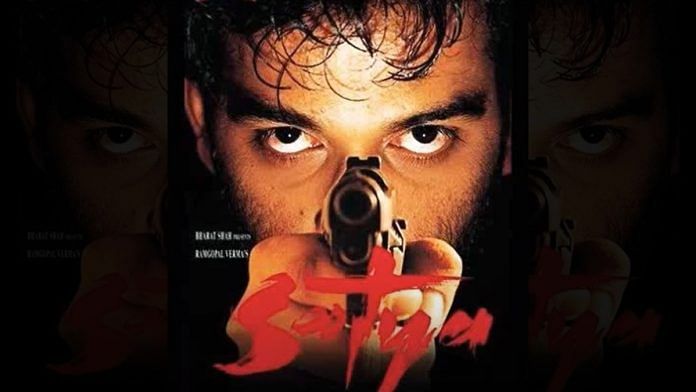

This is a dialogue that defines the power of the movie Satya, a directorial venture of Ram Gopal Verma which hit the screens in 1998. At a time, when Bollywood movies were exploring the urban class and its lavish lifestyle, Satya did come as a shocker. Cutting across the rising gore and violence in Mumbai city, this movie reflected the ground realities.

Mumbai, known as the “city of dreams,” where people from all over the country come to fulfill their aspirations and try to climb the social ladder but the saturation, lack of resources and rampant inequalities shatter the dream of many. These people are pushed to the peripheries of the society and are forced to grind under the garb of false hopes. A documentary recently released by OTTplay “Satya: Ab Tak Pachchees,” celebrating the legacy of this pathbreaking film mentions that this film for the most part was unscripted and attempted to encash the calibre of the actors as well as the milieu that it was set in.

Satya, portrayed by J. D. Chakravarthy, lacks a backstory, arriving in Bombay for a job and thrust into violence. The film’s writers, Saurabh Shukla and Anurag Kashyap, chose this unconventional approach, breaking away from traditional filmmaking templates.

“Satya” serves as a societal mirror amidst Bombay’s modern glamour, revealing a shadowy world where crime, politics, and economy intersect amid aspirations, poverty, and love, casting a dark cloud over the city’s landscape.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Bombay experienced upheavals and uncertainties, including gang rivalry, textile mill strikes, and communal disharmony. Alluding to the notion of ‘Chronotope’ proposed by Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin, the movie “Satya” uses film space to create an archive of incidents, allowing people to relate to the city’s fragility and polarization.

People participated in what is called a ‘memory citizenship’ by American literary scholar Michael Rothberg. The uprising crime rates of the city, the shattering dreams of the urban poor, and the hints of wreckage in the social fabric of the country were lived realities of people and Satya’s documentation only accentuated the visualization of these memories. The claustrophobia of the dingy cells in the chawls, the grit and grime, the blood splatters, and the raw language of the city dwellers are all depicted without any censorship.

Gerard Hooper, the cinematographer of the movie notes that the city in itself is a character. The use of handheld cameras and frequent use of jerks alongside shaking shots impart a sense of tension and trauma inside the viewer.

Abandoned factories and the drab alleyways get the pride of place and most of the action happens on the streets. Professor of Cinema Studies Ranjani Mazumdar notes “The street evokes a sense of power when gangs control it.” The constant movements impart freedom to claim the roads that they are forced to occupy.

The politics of representation of the marginalized as against the socially approved apparatuses such as police and law, raise questions about the distinction between right and wrong.

Hannah Arendt’s “Banality of Evil” concept finds resonance in Satya, where evil becomes mundane, desensitizing people to its horrors. Satya’s abrupt intrusion and the ensuing police violence in Vidya’s home serve as a stark wake-up call, symbolizing how crime infiltrates and disrupts the peaceful world, with blood as a chilling reminder.

Satya depicts this coaction by structurally decoding examples from real life. Dawood Ibrahim’s funding for various Bollywood movies and the murder of renowned film and music producer Gulshan Kumar find overt references in the movie. Thus, raising questions on the political economy of celluloid depictions.

Another essential tenet of the movie is the efforts to break away from the stereotypical images of the underworld. Ganjis and baniyans replace the big black coats, and cigarettes and local tharra (alcohol) replace the smoking pipes. The gangsters are humanized in a way that allows the viewers not to sympathize but to understand the lifestyle of these so-called “kings” which is twice removed from the luxurious amenities that one would think, they have.

One of the significant scenes is where Bhiku is talking to his team member on the phone about killing someone and at the same time his wife and children pass over in the background running after each other.

The song’s lyrics, “Goli maar bheje me, bheja shor karta hai, bheje ki sunega toh marega Kalu,” symbolize the gangster’s need for swift action over contemplation. Professor Mazumdar highlights how the city’s aspirational values influence characters like Bhiku Mhatre’s quest for power and Satya and Vidya’s pursuit of freedom and love. This reflects the inner turmoil of gangsters in a socio-political environment that hinders redemption.

As Satya celebrates 25 years of its release, the movie stays relevant even today. The avant-garde filmmaking style and the impactful narrative make it a cult classic. A film that archives the journey of the urban city from the ‘other’ side.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.