New Delhi: A year ago, a wave of mass protests swept Bangladesh against 15 years of Awami League rule under Sheikh Hasina. During the five-week agitation, at least 1,400 people were killed, many by security forces, and thousands more injured, according to a United Nations report. On 5 August 2024, Hasina resigned as large crowds of demonstrators surrounded her residence. She fled the country for India the same day.

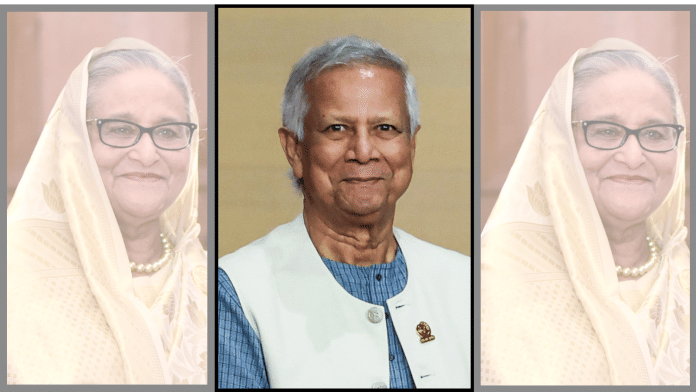

Three days later, Muhammad Yunus was appointed to lead an interim government. His promises were ambitious—restore democratic institutions, reform the security sector and end the era of repression.

His government quickly banned the Awami League, began investigating atrocities committed under the Hasina administration, and pledged a future with where human rights would be respected.

Yet, a year on, the country remains deeply unsettled, and while some of the worst abuses have ceased, rights activists say the new government is falling short of its bold agenda.

“There is no comparison between Hasina’s rule and now,” Meenakshi Ganguly, deputy director, Asia Division, Human Rights Watch (HRW), told ThePrint. “During Hasina’s rule, people were disappearing and were executed extrajudicially in a way that was unprecedented.”

“That level of brutality isn’t happening anymore but progress is stalling,” she said. “Dr Yunus came in with a bold human rights agenda to restore democracy. That agenda is now stuck, bogged down by immense political pressure.”

In a report last week, the rights body noted that “the interim Bangladesh government of Muhammad Yunus is falling short in implementing its challenging human rights agenda”.

Odhikar, a leading human rights organisation in Bangladesh, also indicted the interim government.

It noted in a report that between 9 August 2024, and June this year, 29 incidents of mob violence, 61 deaths in jail and 6,390 incidents of political violence had come to the fore in the nation. The political violence saw individuals injured, assaulted, attacked, threatened or sued.

Ganguly acknowledged limited improvement in abuses since the transitional government led by Yunus took charge. “Yes, there have been attempts (towards improvement). The most egregious abuses, enforced disappearances, state killings and politically motivated executions have stopped. But the structural issues remain unresolved,” she said.

Other experts too asserted that deeper structures of repression and impunity remain largely intact.

“In raw numbers, violations have decreased since 5 August (2024),” Rezaur Rahman Lenin, a prominent human rights activist, told ThePrint. “But that doesn’t tell the whole story. What matters is the nature and context of violations—and in that sense, little has changed.”

Lenin, who has long tracked state repression and judicial dysfunction in Bangladesh, said the country continues to witness rampant political violence, mob lynchings and abuses by security forces.

He was rather of the view that law and order had worsened. “Mob violence has claimed more than 100 lives since the interim government took charge. Reports of extrajudicial killings and police abuse continue, while artistic and academic expression face ongoing constraints. Rather than improving, the rule of law appears to be deteriorating.”

Also Read: On Dhaka’s streets, palpable anger toward India for ‘sheltering’ Hasina, acting ‘superior’

Grim statistics under interim govt

According to HRW, between August and September 2024, police filed criminal cases against 92,486 people, many for murder. Nearly 400 former Awami League ministers and officials were named in more than 1,170 cases.

One prominent detainee is former North Dhaka mayor Mohammad Atiqul Islam, who has been held since October in connection with at least 68 separate cases of murder or attempted murder during the 2024 protests. Records show that 36 of those incidents occurred while he was outside Bangladesh. As with most high-profile cases, formal charges are yet to be filed, the rights body noted.

“This tactic—filing an FIR naming hundreds of people, many unnamed—was a hallmark of Hasina’s abuse. That process has continued,” Ganguly said.

While the Yunus administration claims it is dismantling the previous regime’s processes, critics believe it is replicating its political bias.

In February, the government launched ‘Operation Devil Hunt’, a sweeping campaign that led to over 8,600 arrests. Many of those detained were said to be Awami League supporters. Many others were arrested under the Special Powers Act, a draconian law allowing preventive detention.

On 16 July, 2025, in the town of Gopalganj, Hasina’s political stronghold, and the birthplace of Bangladesh’s founding father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, five persons were killed in violence between Awami League supporters and security forces following a student-led rally.

Ten murder cases were filed against more than 8,400 unnamed suspects. The government denied orchestrating mass arrests, but rights groups say otherwise.

Another report, by Ain o Salish Kendra, a human rights organisation in Bangladesh, said that from January to June this year, Bangladesh witnessed 270 instances of political violence, resulting in 2,770 injuries and 65 deaths. Awami League supporters were the most affected group, involved in 25 incidents, with 339 injured and six killed.

“We’re deeply concerned about the sweeping allegations against Awami League supporters, many of whom are being accused of murder during the protests without credible evidence. In most cases, bail is denied. This signals that the police have not reformed their old patterns of politically motivated abuse,” Ganguly told ThePrint.

Odhikar noted that despite promises of accountability, torture and custodial deaths remain prevalent, and that 61 people have died in custody since the interim government took charge.

One controversial death was of Sheikh Jewel, a Bangladesh Nationalist Party activist, who died while in police custody in Muradnagar, Comilla, in June. The police claimed he had a heart attack but his wife, Shilpi Begum, alleged that he was tortured to death. An inquest found injuries on his body.

Odhikar reported another controversial case of April this year, in Barisal, where two teenage cousins were shot at during an anti-narcotics operation by a joint force of security agencies. One, Siam Molla, died on the spot. The Rapid Action Battalion filed a case regarding the incident but documented the boys’ age as adults. Birth certificates later confirmed they were both 17. Local protests followed, demanding justice and a transparent investigation.

Govt efforts & resistance

The interim government did make some institutional gestures towards justice in the past year.

In August 2024, it ratified the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance and formed a commission to investigate enforced disappearances during Hasina’s rule. The commission has received more than 1,800 complaints and completed two interim reports.

HRW said the probe commissioners have collected significant evidence against the previous government but said security forces have limited their cooperation, and are resisting efforts to hold the alleged abusers accountable, many of whom are still security agency members.

Few in the security services have been prosecuted. BBC reported that only 60 police officers had been arrested for their role in the deadly violence in July and August last year.

While the new commissions are working to modernise laws in Bangladesh, the government has met with resistance from conservative groups, HRW noted.

In May, 20,000 supporters of the Islamist group Hefazat-e-Islam marched in Dhaka, denouncing proposed reforms aimed at gender equality.

The Women’s Affairs Reform Commission, formed by Yunus’s administration, had recommended landmark changes: criminalising marital rape, equal inheritance rights, equal parental rights, and a gender-based violence-free society.

Hefazat protesters shouted “men and women can never be equal”, and demanded the commission be dissolved.

“This is one of the issues we are deeply concerned about. We’re seeing a rise in extremist voices who do not believe in LGBT rights, who do not believe in women’s rights,” Ganguly said.

She added that “rising anti-Muslim rhetoric in neighbouring India may be fuelling retaliatory extremism in Bangladesh, particularly against Hindus and LGBTQ individuals”.

Last month, mobs damaged at least 14 homes belonging to Hindu families in Rangpur. Abuses in the Chittagong Hill Tracts against minority communities also persist.

Similarly, even the press is under pressure. In the past year, at least 196 journalists have reported harassment from political groups or non-state actors.

Eleven reform commissions, focused on everything from the judiciary to police reform to electoral transparency, have submitted recommendations. But few have been implemented. Political consensus remains elusive, and the window for lasting reform may be closing.

The interim government has invited the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to support its reforms. A special expert on extrajudicial executions visited the nation in recent months to assist with forensic investigations related to disappearances.

But Yunus has resisted allowing the UN Human Rights Council to set up a formal monitoring mechanism, Ganguly said.

Despite all this, Ganguly has hope. She insists that the international community should not turn away and the promise of a new Bangladesh is still alive, if precarious.

“There’s a justified anger towards the Awami League for its years of authoritarianism and partisanship, but that anger is now driving vengeance, not justice. If Bangladesh wants to heal and rebuild as a democracy, it must move beyond retribution and towards inclusion,” she told ThePrint.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)