Rare earths are among the most critical raw materials on the planet, deeply embedded in the technologies that underpin modern life. Yet few people had even heard of them until the eruption of the US-China trade war thrust them into the limelight.

With obscure names like gadolinium and dysprosium, rare earths are used across sectors — from semiconductors and iPhones to MRI machines and cancer treatments. More recently, demand has been propelled by the green tech that’s helping to cut carbon emissions.

The world has long been reliant on China for rare earths — something the country has used to its advantage in responding to the trade war initiated by US President Donald Trump. China has leveraged its dominance of the supply chain to retaliate against American tariffs by restricting the export of rare earths.

Unwinding these limits has been a flashpoint in trade talks between the two superpowers. The tighter Chinese controls have also injected momentum into US efforts to source alternative supplies — both at home and from allies such as Australia.

What are rare earths?

The rare earths are a set of 17 metallic elements, grouped together because of their chemical similarities. Their optical, magnetic and electrical properties make them suitable for a wide variety of applications.

Terbium and yttrium, for example, enable the vibrant colors on smartphone and television screens, while the ability of cerium to facilitate chemical reactions means it’s commonly used in catalytic converters to clean up car exhaust fumes.

Neodymium and praseodymium have been harnessed to create permanent magnet motors. These can convert the electricity stored in a battery into motion — to rotate the wheels of an electric vehicle, for instance. They can also work in the opposite direction to turn motion into electricity, such as from the spinning of wind turbine blades.

Just how rare are rare earths?

Contrary to their name, rare earths are actually quite common in the Earth’s crust — cerium is more abundant than tin or lead. But the challenge is finding them in a high enough concentration in one place for mining to be cost-effective.

Extraction can be harmful to the environment as large amounts of water and energy are needed to separate rare earths from the rocks in which they reside. There’s also a risk that mining them will contaminate local soil and groundwater, as rare earths are often found together with radioactive elements like uranium and thorium.

Who are the top suppliers of rare earths?

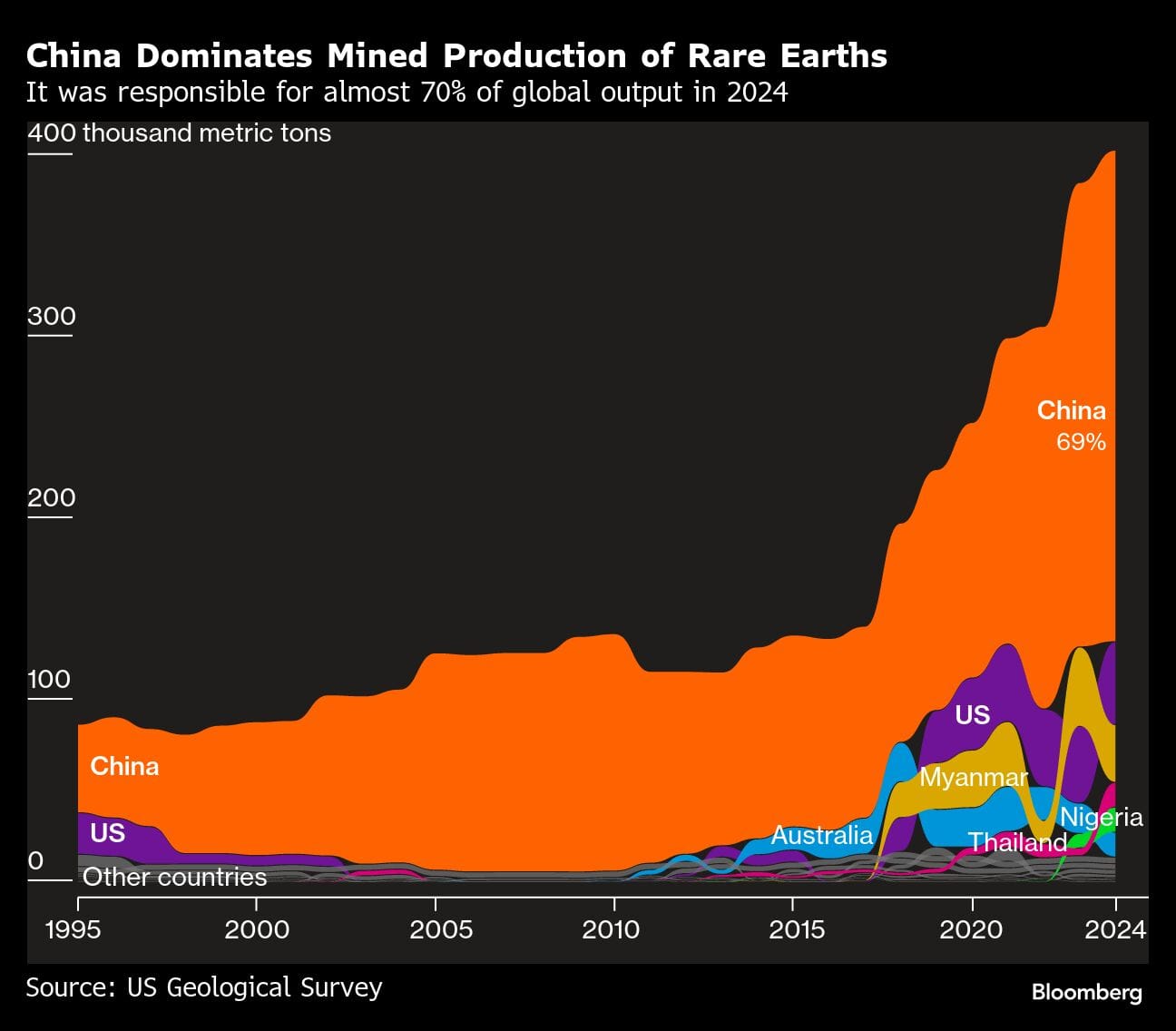

The US was the world’s top producer across the 1960s to 1980s, but it fell away as China began to scale up its efforts. Low-cost operations enabled the East Asian nation to flood the market with cheap rare earths and establish a near-monopoly over the global supply chain.

China is responsible for around 70% of the volumes dug up from mines. It produced 270,000 metric tons of rare earths in 2024, doubling its output over five years, according to data from the US Geological Survey. The US came a distant second with 45,000 tons.

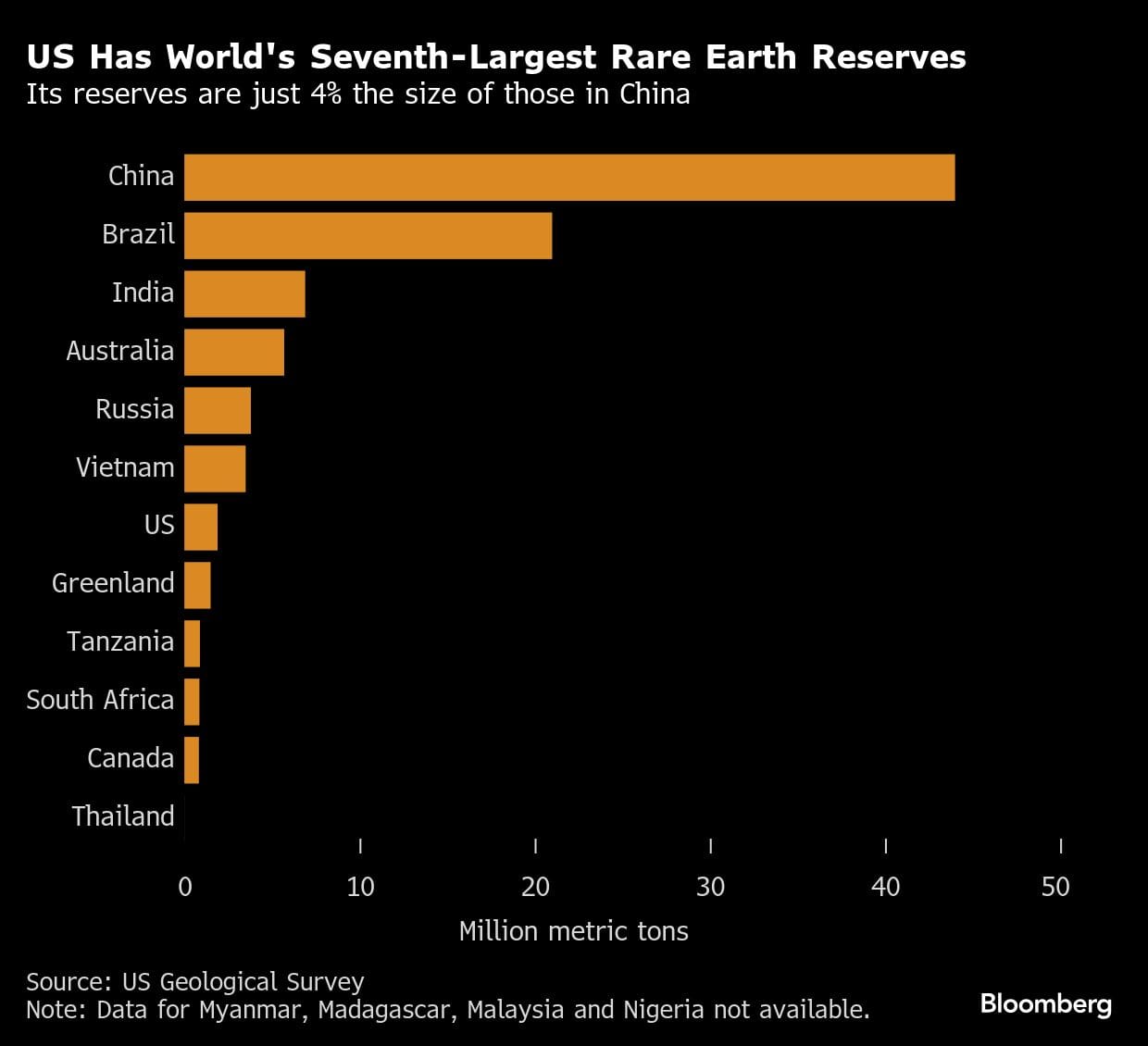

Underpinning China’s dominance is the fact that it’s home to almost half the world’s reserves of rare earths, which are deposits that can be economically extracted. Its 44 million tons of reserves are more than double those found in second-place Brazil.

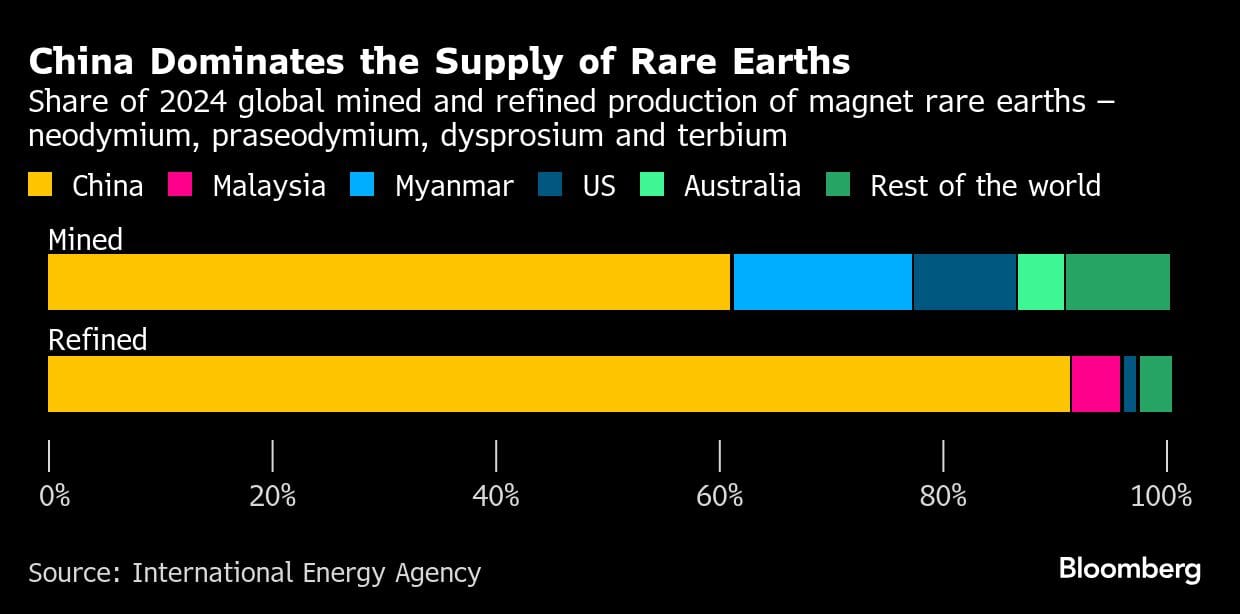

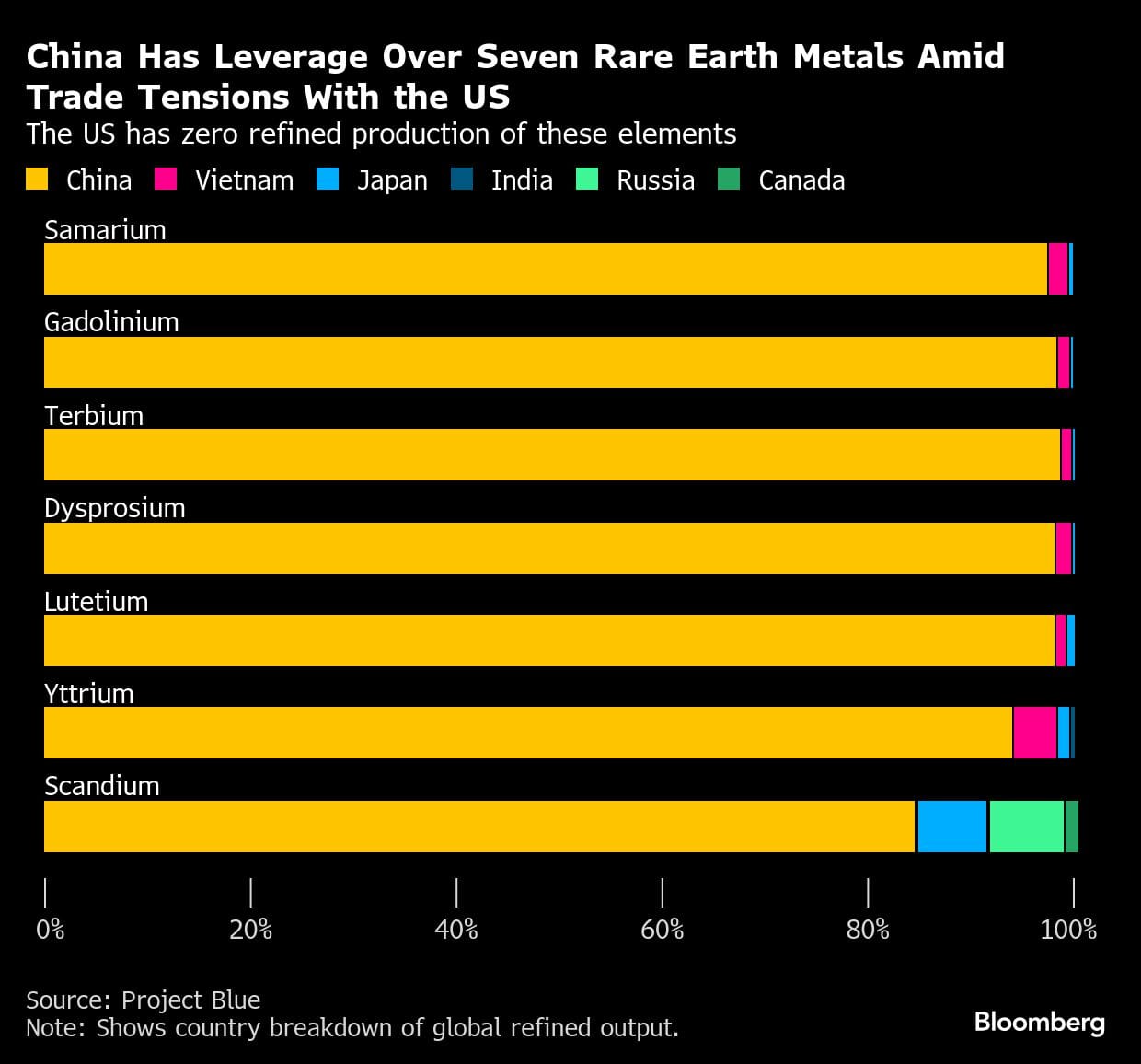

The US is just seventh in the pecking order, with about 1.9 million tons of reserves. It also has little capacity to refine them. In fact, the few countries that can mine rare earths often still need to send them to be refined in China.

How has China leveraged its control over rare earths?

China has long recognized its edge when its comes to rare earths. Leader Deng Xiaoping said back in 1992 that “the Middle East has oil, China has rare earths.”

Its sway over the market became apparent in 2010 when it blocked exports to Japan for two months after a flare-up of a maritime border dispute. That sparked a long road of Japan trying to reduce the dependence of its rare-earths supply on China, although it still only trimmed it from 80-90% to 60%, former Economic Security Minister Takayuki Kobayashi told Bloomberg News.

China’s central government has a firm grip over the country’s rare-earths production and exports. It’s been flexing its muscles in recent years as tensions ratcheted up with the US over access to semiconductors. In late 2023, China expanded its restrictions on the export of technologies used to process rare earths, bolstering its command over refining activities.

How has China used rare earths as a weapon in the trade war?

Going beyond tit-for-tat tariffs, China added seven rare earths and permanent magnets to its export control list in early April, meaning companies need to secure special licenses to send these materials overseas. This echoed similar restrictions it rolled out over the last two years on other critical minerals, such as gallium, germanium, graphite and antimony.

The curbs on rare-earth exports included some “heavy” rare earths, which are almost exclusively produced by China and typically more valuable. Lutetium, for example, serves as a catalyst to break down hydrocarbons in oil refineries.

China’s rare-earth constraints put pressure on US companies. Ford Motor Co. temporarily shuttered a factory in Chicago in May because it ran short of rare-earth magnets. The fallout extended to other parts of the world, too, including the European Union, where firms reported several production stoppages.

A resumption of rare-earth shipments was top of the Americans’ wish list during trade talks with China in June. The two sides reached a framework agreement and China said it would “review and approve eligible export applications for controlled items in accordance with the law.”

However, the Chinese Commerce Ministry unveiled new rare-earth restrictions in October, citing national security concerns. It said that companies overseas will have to obtain its approval to export some goods if at least 0.1% of their value comes from certain rare earths sourced from China. An export license will also be required for products made using Chinese technology related to rare-earth mining, smelting, recycling and magnet-making.

The measures are similar to those the US has used to block Chinese companies from accessing cutting-edge chips and the tools to produce them. China’s Commerce Ministry guided that export permits for military uses are unlikely to be approved, while those for some semiconductor and artificial intelligence applications will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis.

How is Trump trying to boost US production of rare earths?

The US relies on China for 70% of its rare-earth imports. It’s a dependency that leaves the American military-industrial complex vulnerable, as the F-35 fighter jet requires more than 900 pounds (408 kilograms) of rare earths, according to the US Department of Defense.

Trump wants to increase domestic supply of rare earths. In March, he signed an executive order invoking wartime emergency powers to expand American production and processing of critical minerals and rare earths. The aim is to provide more financing, loans and other investment support, and accelerate the permitting process for new projects.

The president then launched a probe into the US critical minerals supply chain in April, ordering Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick to determine whether the country’s reliance on imports poses a threat to national security and if tariffs need to be applied. The results of the investigation must be delivered within 270 days.

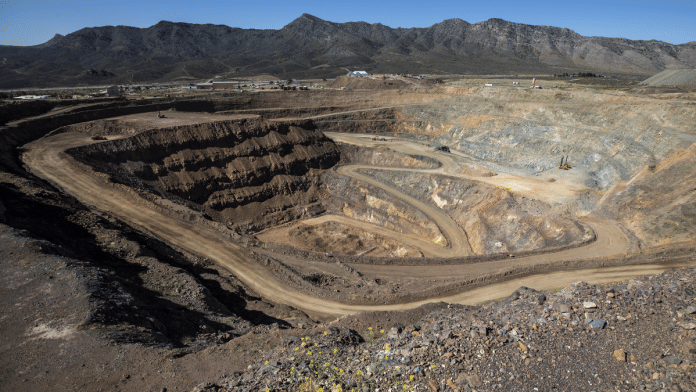

Import taxes wouldn’t translate to an immediate surge in US supply. There’s only one operational rare-earths mine in the country at present: MP Materials Corp.’s Mountain Pass mine, reopened in 2018, in California’s Mojave Desert. Getting other projects up and running would be a yearslong and expensive process. In the meantime, American businesses that need rare earths would likely pay more for their imports if new tariffs were introduced — assuming China allows these materials to be exported.

In July, the US Department of Defense agreed to a $400 million equity investment in MP Materials to create an industry champion. The government will become the company’s largest shareholder and the money will help fund a new manufacturing plant for rare-earth magnets. The DoD will provide a 10-year guarantee that all the facility’s products will be purchased.

Trump is looking beyond US shores for rare earths as well, having signed an agreement at the end of April to exploit Ukraine’s critical minerals. He’s pointed to the European country as a source of rare earths but it doesn’t have any major reserves that are internationally recognized as economically viable.

In October, the Trump administration agreed a landmark deal with Australia’s government to pump cash into the Australian critical minerals industry. The two countries will each spend more than $1 billion in the first phase of the pact, and Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said the deal could eventually extend to $8.5 billion worth of projects.

Australia is home to the world’s fourth-largest reserves of rare earths and has long sought to position itself as a viable alternative supplier to China. Still, many of its projects are years away from being operational.

(Reporting by Joe Deaux and Martin Ritchie. With assistance from Jacob Lorinc)

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.

Also Read: America gifted China its rare-earth monopoly — and India helped too