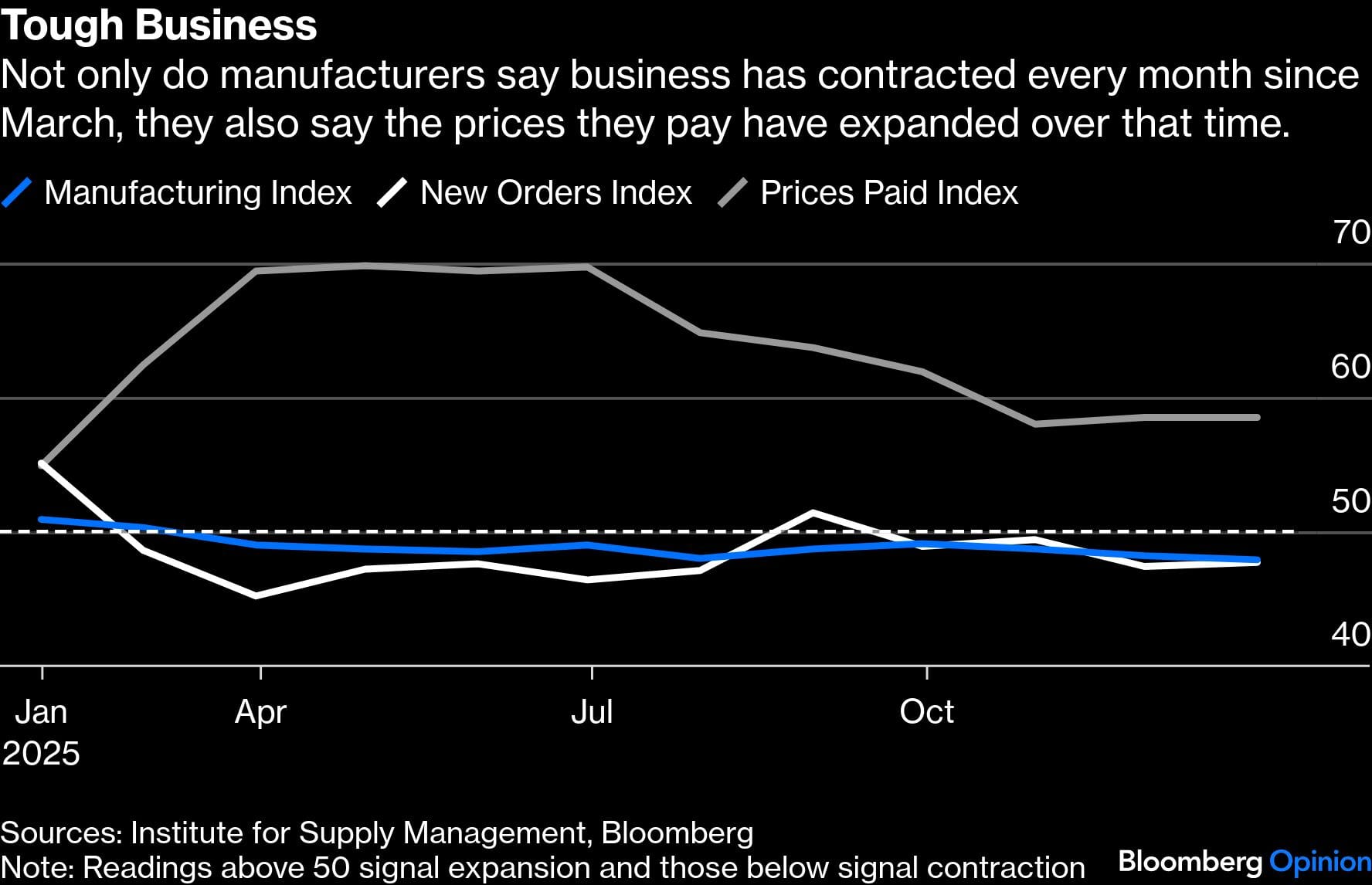

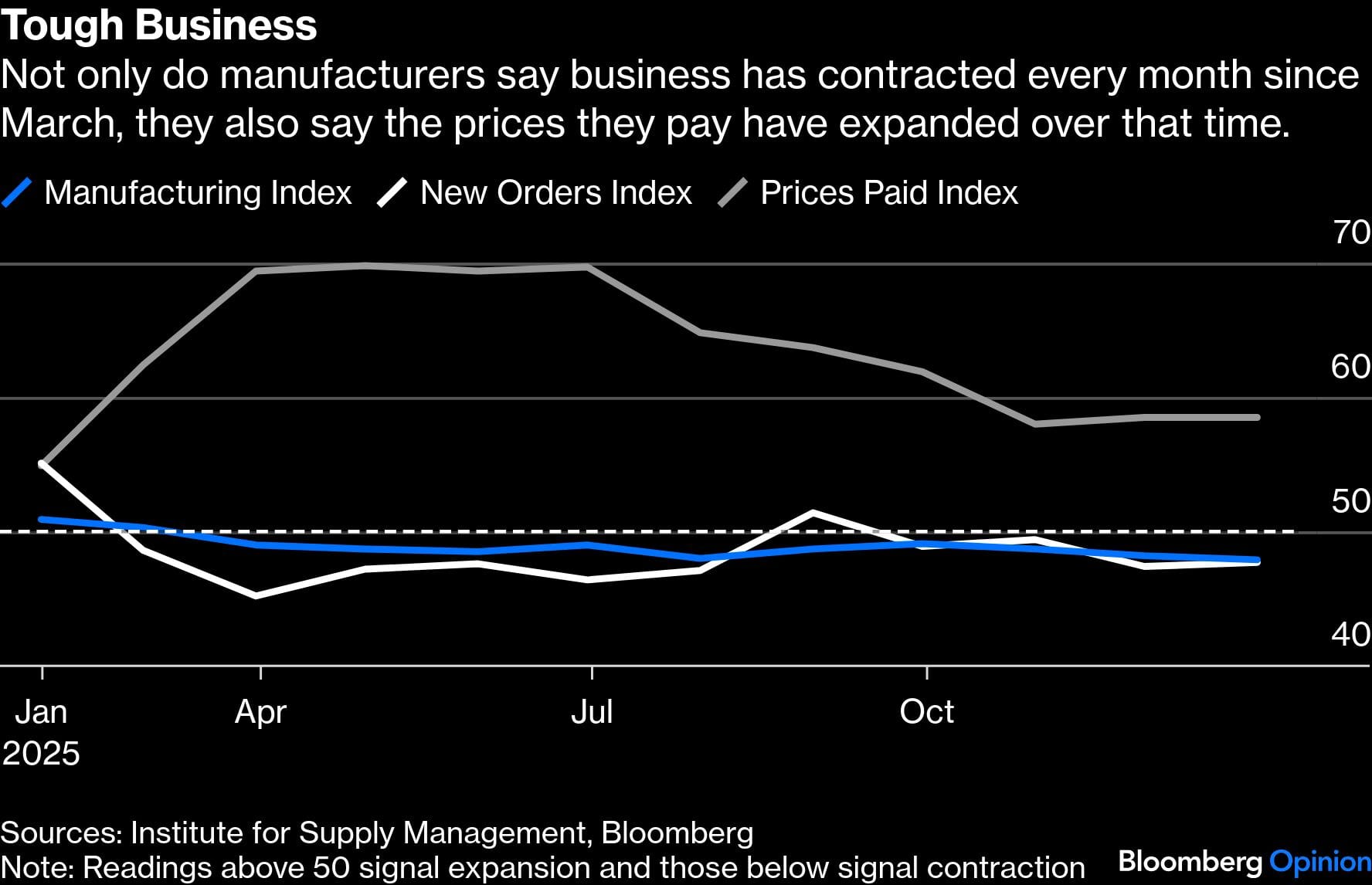

US manufacturing ended 2025 with a thud, capping a rough year for the sector. To recap, manufacturers shed 63,000 jobs, according to the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It wasn’t just labor that was hurting. The Institute for Supply Management’s manufacturing index clocked in at 47.9 for December, marking the 10th consecutive month of contraction as new orders were especially weak and costs at historically elevated levels.

Then there’s the Federal Reserve’s Beige Book of regional economic conditions and surveys from the regional Fed banks, which have repeatedly documented cases of manufacturers delaying hiring and investment amid weak market conditions, rising costs, shrinking profit margins and persistent uncertainty. As for the “hard” data, manufacturing capacity and output, while incomplete, sagged through the Fall.

Overall, the evidence reveals a sector that’s stagnant at best, and a long way from the manufacturing renaissance President Donald Trump promised when he took office for a second time a year ago. No wonder administration officials have pivoted from predicting a factory boom in 2025 to now saying it will happen in 2026 and beyond.

Call me skeptical.

Better tax, regulatory, and monetary policy should indeed provide a tailwind for manufacturing, but the sector will probably continue to struggle. If so, Trump’s tariffs will be a big reason why.

The most basic problem is that modern American manufacturing depends on international trade. As documented by the National Association of Manufacturers, 91% of manufacturers use imports to make things in America, and these inputs constitute around half of all US goods imported each year. Advanced industries such as semiconductors, aerospace and medical devices are particularly particularly reliant on complex global supply chains and cutting-edge components from around the world.

Manufacturers in the US export more than $1.6 trillion in goods each year, or about a quarter of their output, and are a major destination for billions of dollars in annual foreign direct investment. Producers involved in goods trade (imports and/or exports) are large and growing employers – home to around 80% of all US manufacturing workers.

In short, it’s a sector that’s still very large and increasingly very global – or at least it was.

Trump’s broad and indiscriminate tariffs confound domestic manufacturing operations in myriad ways. Most obviously, they increase production costs – even when firms buy American. Tariffs on steel, aluminum and copper drove prices in the US for these critical materials to significant premiums over global benchmarks. Tariffs on parts and equipment raise the same issues.

Buying local often isn’t an option. The National Association of Manufacturers estimates that firms running at full capacity could supply only 84% domestic producers’ input needs, meaning at least 16% must be imported. (The numbers are much higher for certain commodities such as aluminum that are primarily sourced from abroad.) The association’s calculation assumes that alternate inputs exist, but they routinely don’t. Roughly half of US goods imports in 2024 were between related parties, with especially high concentrations in transportation equipment, chemicals, computer and electronic products, and machinery.

The prevalence of these intra-firm transactions means that multinational producers in the US are often stuck paying hefty new taxes on components and equipment shipped from their own facilities abroad for further processing in America – an intricate and efficient global supply chain that can’t be rejiggered overnight (if at all).

Tariffs have ensured that domestic producers pay significantly more than their foreign competitors for the same inputs — a dynamic that makes US investments less attractive and American goods harder to sell both here and overseas (and ironically dampening tariff protection for downstream US manufacturers). Foreign retaliation against US exports, which was more muted than expected in 2025 but is still occurring, amplifies these headwinds.

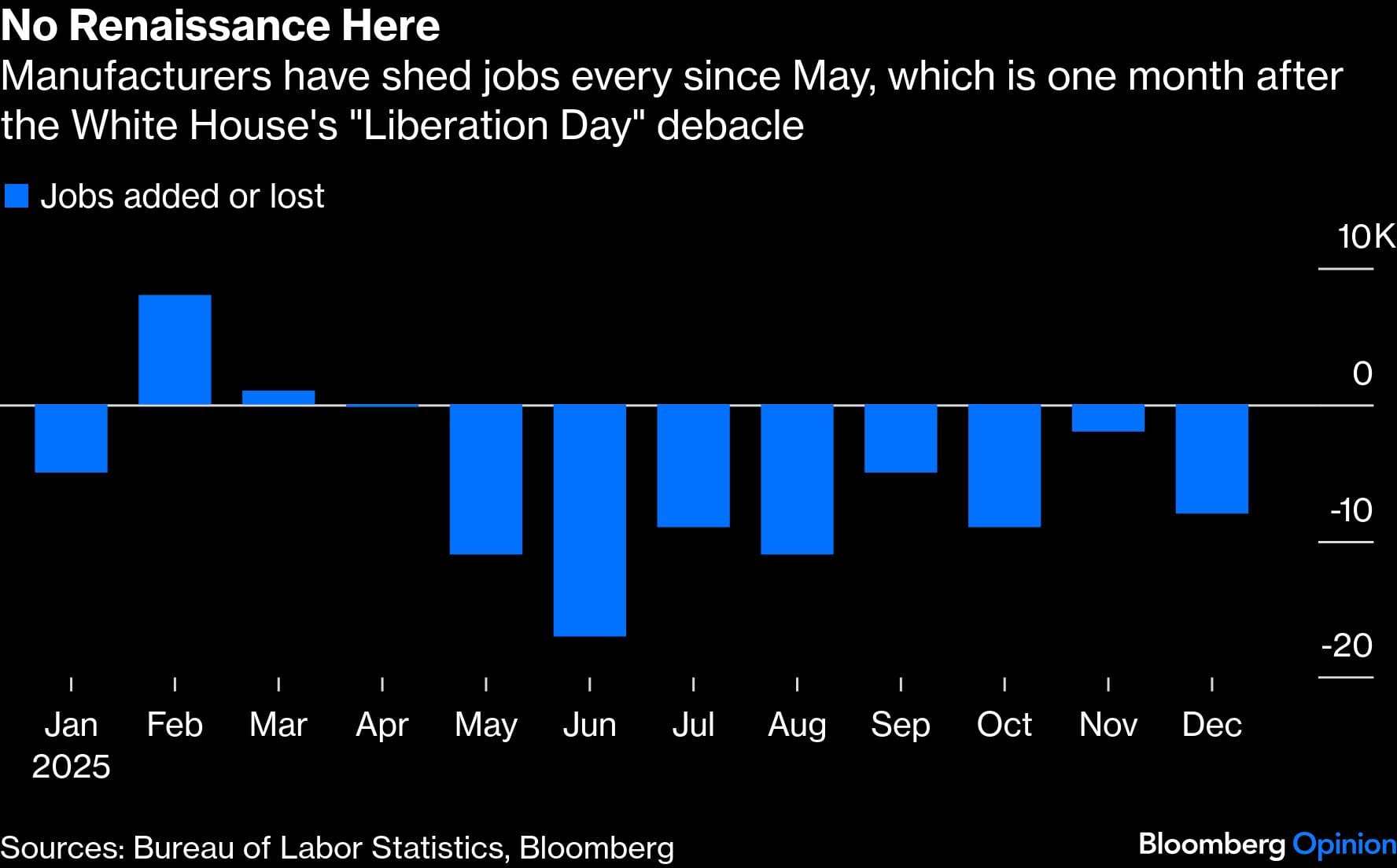

The second problem stems not from the level of tariff rates, but how they’ve been implemented. Manufacturers might be able to adjust to a permanent, uniform and one-time increase in tariffs, but what they face instead is an ever-changing mishmash of opaque and complicated import taxes enacted by executive fiat. Last year, the US tariff code was amended 50 times, a non-pandemic record and far above the pre-Trump standard. These changes, along with constant tariff threats, caused an unprecedented increase in trade policy uncertainty, which weighed on manufacturers’ hiring, capital expenditures, supply chain and sales plans even when tariffs weren’t actually implemented.

Complexity has imposed additional costs. By the end of last year, 20 different tariff measures applied to significant volumes of US imports, up from just three in 2017. These unilateral taxes vary by product and country, as well as by how they “stack” atop one another, with some imports facing multiple taxes and others only one. New rules also apply for certain metals content, trade deals, product exclusions, and other special factors.

Calculating the correct tariff on a single product has therefore gone from a relatively stable and straightforward process to one that even certified customs brokers can’t grasp, with big penalties for errors and huge costs, regardless. As Bloomberg News documented, tariff complexity has pushed US firms to scuttle major operational decisions until they have more clarity. The tariffs’ variability also amplifies their macroeconomic costs, and Federal Reserve economists economists estimate that domestic manufacturers will pay $39 billion to $71 billion annually to comply with the new regime, representing time and money they can’t spend on their businesses.

The harms to manufacturers are consistent with research on past tariff episodes and help to explain why the sector struggled in 2025 — and why things might not get much better this year. Recent forecasts also suggest caution, with manufacturers and supply chain professionals predicting continued headwinds due to the costs, uncertainty and complexity of tariffs. And the Supreme Court won’t save them. If it invalidates Trump’s “emergency” tariffs in the coming days, administration officials have promised to invoke alternate authorities to recreate them.

Global supply chains took years to develop. They’ll take even longer to reorganize and will do so at great cost if, that is, they don’t break altogether in the meantime.

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Scott Lincicome is an economist with the Cato Institute. He specializes in domestic policy and international trade.

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.

Also read: A new Indian foreign policy consensus is emerging. That India isn’t a great power yet