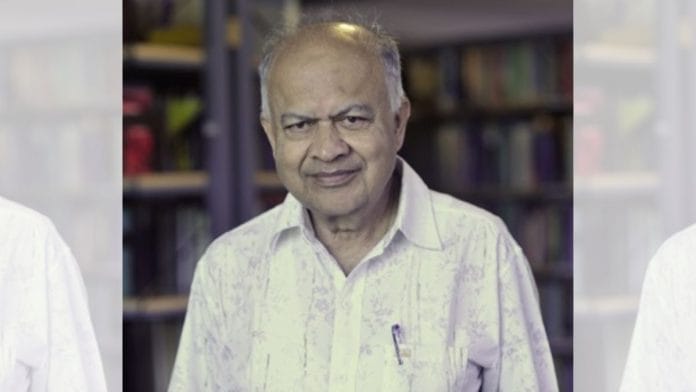

Astrophysicist Dr Jayant Narlikar was a rare scientist who was known for his efforts to make science accessible, bringing the wonders of the cosmos closer to the public. He founded the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics in Pune, where he planted a sapling descended from the apple tree under which Newton is said to have discovered gravity—placing it beside a statue of the scientist in the institute’s garden. Dr Narlikar passed away Tuesday.

In a 2015 episode of Walk the Talk with Shekhar Gupta, Narlikar spoke of his Narlikar-Hoyle theory, the importance of curiosity in keeping a scientist young, described the Padma Bhushan he received in 1965 as “a pat on the back from the nation”, and shared his frank views on astrology.

Here is a transcript of the interview, edited for clarity.

Shekhar Gupta: Hello and welcome to Walk The Talk. I am Shekhar Gupta at Pune University’s IUCAA, The Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics. I stand here in this garden with all these great icons of science, particularly astronomy and astrophysics around the world.

There is Galileo, there is Aryabhata, Einstein and Newton to my left. And among these icons of many centuries, a living icon, who I have the privilege of having as my guest today, Professor Jayant Narlikar. Welcome to WalkTheTalk.

It is such a privilege, I feel honoured.

Jayant Narlikar: Welcome to IUCAA.

In fact, I feel honoured that you considered it worth your while to talk to somebody who, you know, knows nothing about science.

Oh well, it’s a pleasure talking to you on any topic.

Thank you, sir. So, you built this garden, you built this institution.

Well, I should confess that I had good help in all departments when this centre was being built. So, I was really fortunate. So, I won’t take the credit myself, but like to share it with so many others.

Right. But you know, good academics also have to be institution builders, which I find with academics of your generation. Professor C.N.R. Rao has built a great lab in Bangalore. You built a great lab here.

Yes, this was motivated by Professor Yash Pal, who was the chairman of University Grants Commission, and he felt that in the field of astronomy and astrophysics, universities have very few facilities. So, he needed a centralised facility which would help all the university academics. That is how IUCAA came about.

So, sir, what is astronomy and astrophysics? Let’s start there. I know that you give lectures all over the world simplifying science.

Well, let me say that astronomy is one of the oldest.

Because science is too important to be left to scientists.

That’s true. I agree. We do get a lot of inspiration from outside science. Now, the science of astronomy came from looking at the sky. And you see heavenly bodies, stars and if you can imagine, you can see galaxies. But now with telescopes you can see them much more clearly. So, you have these observational inputs and you would like to know what it is all about. So, the observations you collect form the subject of astronomy. And when you try to understand what is going on, why is the sun shining, why are stars red, white, blue…

Or why is the sky blue?

Or the sky is blue. So, there is physics behind it. So, that takes us to astrophysics. Then, subsequently, people began to discover organic and inorganic molecules in space. And that brought about astrochemistry.

And now the intriguing possibility is life in existence outside the Earth. And that takes us to astrobiology.

So, these are younger sciences. The oldest is astronomy, then astrophysics. So, these are the major thrust areas. But astrochemistry and astrobiology are coming up.

But a scientist, as long as a scientist remains curious, a scientist is always young.

Yes. That’s true. Scientists should always be curious, and you said about youth. I think a scientist is young so long as he is curious.

So, you are as young today at 76, as you were at 26, when you became India’s youngest ever Padma Bhushan winner.

Possibly.

At 26 in the 1960s, you know, it was some achievement. Because at that point people could see scientific talent. Perhaps in a manner that our system doesn’t see now.

Maybe. I always feel that that was a pat on my back from a nation which was expecting more from me.

So you continued to do more and you built an institute.

That was always my feeling.

And I believe when you founded this institution, you brought Isaac Newton in, with the apple.

That’s right. I used to talk about this institution abroad also. Once I was talking in Australia, and I made my usual joke that Newton is sitting under a banyan tree, and he’s wondering how the apple fell out of the banyan tree.

So, that is astrobiology and astrochemistry.

In fact, that is a more difficult problem than the law of gravitation. So, when I said this, of course, there was laughter and so on. Then one Australian scientist told me afterwards, why don’t I get an apple tree planted behind Newton and why don’t I get the descendant of the original apple tree which was in Newton’s garden. I didn’t know it was available, and he told me the chapter and verse where to get it.

Eventually I succeeded and there was one here (points to his right), and one behind Einstein.

So, apple trees in Pune.

Yes. People said apples won’t survive in Pune. You have to be in a mountain climate and so on. But I said let us try. And it did work. For about 14-15 years, we had this. We got apples out of the tree. So, I would say that it was a worthwhile exercise. Unfortunately, the tree died because of some illness.

But I believe you used to get fruits also from that tree.

Yes, we got the fruit and I cut the fruit and left it for my graduate students to share. It’s like Prasad (laughs).

Prasad from Newton.

But I told them simply eating the apple won’t make you an astrophysicist. You have to work hard yourself.

Sir, we go from Newton to Galileo. Because science doesn’t always reward you. To have a scientific temper you also have to pay a price.

Yes, that’s true. Now about Galileo. Another scientist who visited us said that Galileo is a typical, what we call… in a state of asking for money.

I see.

Astronomers are always short of money. So, he said that. It is a very good description.

But sir, over the centuries, scientists who come up with a new idea face resistance.

That’s right.

From the establishment…

Galileo brought in the telescope for the first time. And people would not believe what they saw through the telescope, because it went against their beliefs. So, they said this is all maya jaal (illusion).

But, sir, things are changing. The Pope accepts evolution now.

Yes. The Pope now accepts what Galileo was saying. He had a committee appointed to look into Galileo’s treatment. And then they exonerated him. And said that he was correct in whatever he said.

As Christ would have said, they didn’t know what they were doing.

Yes (laughs).

So, Sir, I bet you have been introduced as an astrologer all over the country. Because in India there is a great confusion. Astronomy, astrophysics. Astrology is simple. You just have to be Panditji.

Probably I would have earned more money.

And frankly more fame.

Possibly.

And politicians would have been hanging outside your house.

But my efforts all the time are to show what is science and what is not science, and, in that sense, we did conduct experiments to show that astrological prediction is of no value. We showed one particular example, if you would like to hear.

Sir.

We had 100 samples of birth charts, or kundalis, of very bright students, and 100 from (students with mental or intellectual disabilities). We mixed them up and asked astrologers to tell us which are which, and they completely failed.

Now you are taking pangas with astrologers. You don’t know what they will do. They can even shift planetary configurations, which you cannot do.

Yes. They might (laughs).

Sir, has your centre been confused for (one that teaches) astrology?

Well, as you might have heard, in our very first year, in the Pune telephone directory our name appeared as ‘Astrology and Astrophysics’. And I said, how did this happen? We had filled out all the forms with astronomy there. So, somebody in the telephone office department may have thought these people may have made a mistake. And he corrected it. So, this is happening, but hopefully we will bring some more light into this whole area of darkness.

But sir, how did we get so confused and when? Because we had a history of scientific research. We had a history of scientific curiosity. We have Aryabhata here, so far back. He imagined what Galileo imagined later. Where did we lose it? When did in the Indian mindset, when did astronomy become astrology?

I think astrology and astronomy came, more or less, together. But whatever historical documentation we have, the planetary astrology, you know ‘Mangal is doing this damage to you’, or ‘Saturn is bad’—all these ideas came from the Greeks.

Oh, I see.

And you find there is hardly any description in the Vedas about astrology. It came later.

It’s a borrowed science.

It’s a borrowed science. It’s what I would call imported superstition.

How would you describe yourself? As a rationalist or a scientist, or both?

Well, I would say I am a scientist trying to reason rationally as far as possible.

And what does it take to succeed? Because you know that it’s tough to teach science to non-science walas. And I know that you’ve been giving lectures, I read some of them on simplifying science…

Yes, I have also written textbooks in popular science languages. So, that helps in making your own mind clear when you explain to somebody else. So, I find that exercise very useful, popularising science. I wish more of my colleagues would undertake that.

I think your example you use is, why is the sky blue? And why do we use red to stop traffic?

You know, I remember seeing a speech by C.V. Raman on why the sky is blue. And I read that and I thought he had done such a good job explaining. He was carried away by enthusiasm. So, I said if a great person like C.V. Raman does this, why not some of us could follow him?

So, please tell us, sir, why is the sky blue? And why do we prefer the colour red to stop traffic?

Well, both are linked. So, when sunlight comes out of the sun, supposing there was nothing in the sky, then what would happen is that light would come to us and we would see the sun shining in that direction. In all other directions, the sky would be dark. This is what the astronauts see, when they go above the Earth’s atmosphere. Now because of the atmosphere, the light gets scattered and the blue color gets scattered most, spread most, and red is least scattered. So, what you see, therefore, is a sky which is dominated by blue color. Now you can ask what happens? Why do we have red light? The red light, which is a danger signal, should be seen from as far as possible. And since red colour is not scattered, or least scattered, it will come undisturbed to you. That is the reason.

And the blue sky gives the sea its blue color.

Yes, because it reflects. Because it spreads the blue colour.

Such a simple explanation.

Yeah, well, once you know the answer, you can appreciate the reason.

Sir, because you can simplify anything, please simplify the basic riddle of your life, which is Big Bang theory versus your own Narlikar-Hoyle theory of what we now call ‘quasi steady state cosmology’.

What is the difference, first of all, between these two theories? So, if you take the Big Bang theory…

Which is generally believed these days by a larger number of people.

Yes, most people believe in the Big Bang. And the idea is that the universe started with a big explosion. And after that explosion, matter, which was created in that explosion, condensed into galaxies and stars and so on. That is the whole history given. It is supposed to have happened in something like 14 billion years. Now, I find, as did my mentor Fred Hoyle, that this requires a lot of…

He (Hoyle) was a legend, you are a legend. I think the two of you were a hyphenated legend.

Kind of you to put me in the same basket as him, but he was great. So, in this particular situation, you can ask questions. Why did the Big Bang take place? What happened at that time? Now, science fails to understand or answer these questions. So, you are told that don’t ask these questions. These are beyond science. You can ask what happened to the universe afterwards. I found that not very scientific.

Because there is no end to a quest in science. It’s not a scripture.

That’s right. So, what I did, or what many of our, I mean, opponents of the Big Bang did, was to say that we don’t like the Big Bang….

Big Bang almost sounds like a theory of creation, as if God or some almighty power…

Yes. That’s why many people like it.

And that’s why many people question it.

Yes, so we said that instead, why not have a universe which had no beginning. It has been there all the time, but it will be oscillating. It is expanding, contracting, expanding, contracting. So that kind of universe has many advantages. Many of these things that we don’t understand in the Big Bang context. One can find their solution to them in the quasi-steady-state version. So, we feel that this alternative to Big Bang deserves to be considered more. And we are trying hard to get it.

And you are still at it.

We are still at it.

But is your tribe growing or is it shrinking?

Well, unfortunately, it is shrinking. And age, of course, takes many of them out. So, like Fred Hoyle, Geoffrey Burbidge, Chip Arp, these were great names. Now, they are no longer on the scene.

But you are there and you are training wonderful scholars.

That may be partly true, but it has, I too have a finite lifetime ahead of me.

Not everything is finite. In fact, if you see the symbol of your lab, which you wear on your chest. It tells us that nothing is finite.

Everything is without a beginning and without an end.

So, this represents cosmology.

Yes, in a certain sense.

And you had this kurta specially stitched?

No, the kurta was there. My wife put this thing.

She’s a mathematics professor.

Yes, that’s right.

You are a family of academicians, I can see.

Yes, we like to think of ourselves as that (laughs).

Where is the joy of teaching and curiosity now? Do you see it declining in India? Do you see science flourishing right now, or stagnating or declining in India?

Well, I am not very happy at the way science is progressing. The support for science from the government has to be at a certain level and what you call the gross developed product, a certain percentage. We have been saying it should be at least 2 percent, and it is less than 1 percent.

Yes, and also, I think there’s a confusion between science and technology or science and engineering.

Yes. Simply supporting technology or buying technology from outside and yes, putting it here doesn’t make you science-friendly. You need to have your own science lab, your own discoveries.

And much of it will have to happen in public, publicly-funded.

Yes. Well, even private funding should be encouraged, because I feel putting everything on the government shoulder is also not quite right.

That’s true. But then again, if you look at this garden, we’ve now traveled from Newton to Galileo to Aryabhata to Einstein—in a way, all products of sort of publicly funded research systems and universities.

One can say, but about Aryabhata one doesn’t know. But Aryabhata was a good teacher and he was respected as such.

Sir, you are a wonderful teacher, too. Many generations of students have respected you. You’ve also taught me at least about the blue colour of the sky and red colour of the traffic light.

I would say that there are so many questions, that sometimes when I give public lectures, at the end of the lecture people come and as me, please sign your autograph. So, I say I won’t give my autograph here. If you write to me and send me a question, I will reply and then my signature will be there. So out of 10, one person might persist. So, all these things led to a small book, which Marathi Vidnyan Parishad brought out. It says science through postcards.

Oh, I see.

So, these postcards I received from these kids.

Curious kids…

And I replied by postcard. So that was called science through postcard and that has come out as booklet.

What a wonderful story. Sir, I can see your face really lights up when you talk about questions, curiosity, things not yet found. And that’s what keeps a scientist going. I think that these are the challenges which make life worthwhile. And that’s what makes an institution like this infinite.

Yes, yes.

Just like your science.

Yes.

It’s been so wonderful having this conversation with you. I mean, I would have would not have made a good astrophysicist because I’m so bad at math, but just to spend some time with you is a privilege.

Well, it’s a pleasure talking to you.

Also read: Indian astrophysics giant Jayant Vishnu Narlikar reshaped our relationship with the sky