Former Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh passed away on 26 December, 2024, at the age of 92. The Congress veteran, and acclaimed economist, was regarded as the architect of India’s economic reforms in 1991.

In 2004, Shekhar Gupta, Editor-in-Chief of ThePrint, interviewed Dr Singh on NDTV’s Walk The Talk, discussing his time at the Delhi School of Economics, the devaluation of the Indian rupee in 1991, his experiences as the country’s finance minister, and ‘converting good economics into good politics’.

Here is a transcript of of the interview, edited for clarity.

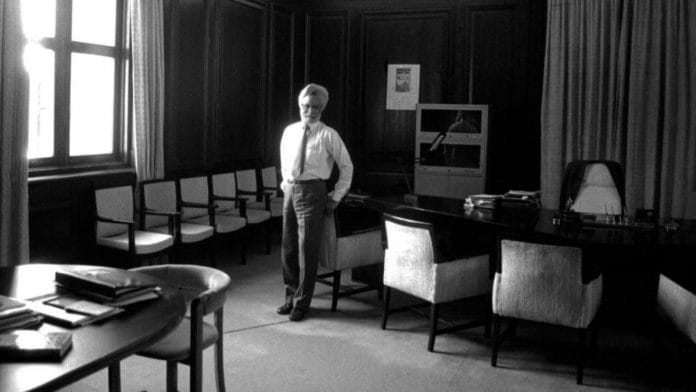

Shekhar Gupta: It’s a very nostalgic setting for my guest today. Dr Manmohan Singh, welcome to Walk the Talk. It’s interesting to have you here, in Delhi School of Economics, where you taught for 3 years. And I think a whole lot of people you taught here have gone on to run India’s economic policy, corporations, so much.

Manmohan Singh: Well, I have very fond memories of having been a teacher in Delhi School of Economics. I think some of the most valuable friendships of my life were made during this period. Professor A.K. Sen, Professor Sukumar Chakraborty, Professor Jagdish Bhagwati, and a whole generation of younger economists who have since then made phenomenal contributions to the…

In fact, you have brought many of them into the policy structure, many of them have then run India’s economy.

Well, yes, I think Bimal Jalan was one of the persons I picked for the Ministry of Finance when I became chief economic adviser. Montek Ahluwalia was another distinguished economist who I brought to the government. Rakesh Mohan is yet another distinguished person whom I brought (to the finance ministry), who is now deputy governor of RBI.

And even among the IAS, I think I picked up a large number of talented young people to work for me when I was minister of finance.

Dr Singh, tell me something. You taught economics here between 1969 and 1971. Before that, in Punjab University, and at Oxford, and later lecturing on commerce and trade. It was very different from the economics you practiced when you became finance minister.

Well, times have changed. In the ’50s and ’60s, there were very few people in the world, including people in the West, who differed from what India was trying to do. Those were the days of Rostow’s takeoff into self-sustained growth. But all that you needed for an economy to take off was a large dose of public investment and, thereafter, the economy will look after itself. We had, I think in the late ’50s, an MIT project. The MIT people were closely involved in the planning of economic policy in India. And there was no difference between our planning commission and the advice that came from distinguished economists of the MIT, I think.

That was sort of east coast academic advice because the US economy was taking a different direction.

Well, I think, obviously nobody would say that India’s problems are the same as the problems of the United States. I think that was the period when most people believed that in developing countries, because of the lack of adequate development of entrepreneurial skills, private sector limitation, the public sector had to be the lead sector.

Sir, when did you realize that this had changed? That maybe some of what had been taught to you or some of what you had taught was either a myth or that times had left it behind.

No, it was not a myth. I think what India did in the ’50s and early ’60s laid the foundation of what has happened to India since then. If Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru had not invested in modern temples of India, the massive irrigation project, the public sector investment in steel, the institutions of higher learning, the department of atomic energy, space programme, India would not be able to reap the benefit of globalisation which we are now able to claim in the changed environment of the ’90s.

Sir, take me back to 1991, the summer of 1991. What exactly happened when you were actually in the hot seat.

Well, I had no indications that I would be called upon to become the finance minister. I had come back from the South Commission and India was then in crisis. Mr Chandra Shekhar was the prime minister. He asked me to help him as an adviser to the prime minister. I saw at that time that India was in the midst of a deep crisis and I started thinking what to do about it.

In my convocation address at the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore, long before I became finance minister, I set out the elements of a stabilisation-cum-structural adjustment programme which I thought India needed. But I had, at that time, no indication.

Sir, when did you realise that Indian economic thinking or the whole idea in the way India’s economy was managed now had to make such a big turnaround? I won’t say about turn, but such a big change.

Well, I was convinced by the early ’70s when I became chief economic adviser. I think the first paper that I did for Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was what to do with the victory. At that time I said that we had gone too far in imposing an unrealistic control structure.

That liberalisation of the private sector, liberalisation of the economy was required.

Also read: When Indian economy was liberalised—Manmohan Singh’s 1991 Budget speech

So, you first recommended the end of license quota Raj in the early ’70s?

Yes, early ’70s. In fact, the paper that I wrote was in 1972.

But you got the chance of putting that into effect 20 years later.

Well, I was a civil servant. I was chief economic adviser, I was also secretary of economic affairs. Then I became member secretary of the planning commission and people don’t remember, I was one of the persons who took part in the formulation of both the sixth and the seventh (five-year) plan.

These were the only plans where the growth targets were more than fully implemented.

But sir, in 1991, when you took over…just describe the crisis to me when you became finance minister. How bad were things at that point? I believe we had foreign exchange for not even for a week’s imports.

India’s foreign exchange reserves had been exhausted. People who had lent money to Indian banking system, they wanted their money back. And if we had gone that way, we would have to impose such drastic import control that there would have been unimaginable increase in unemployment. A sharp increase in inflation was already evident. When we came to office, prices were rising at a rate of about 20 percent per annum. And our system does not tolerate high doses of inflation.

And India would have gone into anarchy at that point.

Yes, exactly. I think what we faced was a complete breakdown of the economic system of India. The type of things which happened in the Soviet Union, for example, or eastern European countries.

How close were we to that?

We were very close to that.

A few days? A few weeks?

I think, a few weeks. As I said, our foreign exchange reserves were no more than $1 billion, that is two weeks’ imports. Non-resident Indians who had kept money in our country were withdrawing their money. The Indian banking system had borrowed some short-term money from the international banking system.

Those bankers wanted their money back. The aid donors were not willing to give aid to India. Yashwant Sinha, when he was finance minister, he went abroad to Washington, to Tokyo. But I think he drew a complete blank.

So, nobody was willing to help?

Nobody was willing to help India.

So, was that the shock treatment we needed to start changing?

Well, maybe. We are a democracy, but we are also an undisciplined democracy. A crisis concentrates the mind probably at nothing else. But when I became finance minister, in the very first week I said, India is in the midst of a deep crisis, we are going to convert this crisis into an opportunity.

So, was this crisis almost as serious as maybe the 1962 war against China, when the country could have collapsed?

Well, the country’s economy would certainly have collapsed, and the politics then could not also be saved.

But would you say that this was the greatest period of the greatest crisis in Independent India’s economic history? Or do you see any other moment that was comparable?

Well, I think we had a crisis of the foreign exchange in 1957-58. We had, I think, the 1962 events that you mentioned. But in terms of, I think, the consequences for managing the Indian economy, the 1991 crisis was probably the most severe.

Dr Singh, tell me a few things you did at that point. Because your government had just come in, you had to get your vote of confidence, you didn’t have a full majority. So, what were the sort of emergency measures you took? Was it like the equivalent of pumping steroids and oxygen into a patient?

Well, the first thing that I came to realise was that India’s exchange rate had to be changed.

It was too high?

Well, I think the rupee was at an unrealistic level. We had to change the exchange rate, we had to depreciate the rupee. But changing the exchange rate in India has always been a political problem. And here was a government, which was a minority government. Here was a government which had yet to win a vote of confidence. I went to the prime minister and I said, we cannot wait till we get the vote of confidence.

Because in India, the popular mind will link the value of the rupee with national pride.

That’s exactly it. So, I think the first thing that we did was to adjust the exchange value of the rupee in two doses. Now, I had to do that because there were difficulties in going for the straightforward way.

What was the straightforward way?

The straightforward way was devaluation, but I think the cabinet was not prepared. There was opposition from the President. He said, well, you have a government which has yet to win a vote of confidence.

This was Mr (R.) Venkatraman?

Yes. So, we found a way out. I instructed the Reserve Bank to announce a new intervention rate. After a few days, I asked them to repeat it. And the result is, we brought about a devaluation, a depreciation of the Indian rupee.

Without announcing a devaluation.

About 25 percent. The world got the message that here was a government which, despite being a minority government, was able to take the toughest decision.

And, if you remember, that the decision to adjust the exchange rate in the 1960s, I think the decision could not be taken over a period of three years.

Also read: Manmohan Singh on Modi — ‘1st PM to lower dignity of PMO, made vicious hate speeches’

This is the early ’60s? Until (PM) Morarji Desai came, I think.

No, I think the World Bank had proposed a depreciation of the Indian rupee in 1962. Ultimately, it was done in 1966. In between, there were tensions within the government. The government was not able to take decisions. But within 10 days of the Narasimha Rao government, we took some of the most difficult decisions. Take, for example, the adjustment of the industrial licensing policy. We abolished the License and permit Raj within one month of our government. And I was able to report in my first budget speech that India had now a different…

Now, was it a signal you were giving to Indian businessmen or to international lenders and institutions?

Both to Indian businessmen and to international creditors. I think we wanted a regime which would value enterprise, which would value risk-taking. And we wanted to create an environment in which even the foreign investors would have confidence that India now welcomes foreign investors.

Tell me something about your exchanges with Mr Narasimha Rao. Did he understand the need for the change in economics? Because both of you were brought up in a socialist milieu. Him more than you.

Well, Mr Narasimha Rao was most supportive. Without his active backing, I could not have done anything.

But he knew the risks.

Well, he knew the risks and he told me that if the thing succeeds, we will all claim credit. If the things don’t work, well, you will be sacrificed. And I was prepared for that.

So, you were marked out as a likely scapegoat.

Yes, I think I realised that right from the beginning.

Were there moments when you had doubts? When you thought this can go wrong or this is going wrong?

Well, I had some doubts when I presented the first budget. We had, I think, cut subsidies very sharply. In fact, in my very first budget, in the history of India, this has never been done. We adjusted, we reduced the fiscal deficit of the central government by a full 2 percentage points of the GDP. This has never happened before.

And that brings its own pain.

And therefore, we adjusted food subsidies, we adjusted fertiliser subsidies. But then there was pressure from Parliament and the government developed cold feet. And at that stage, I protested. I gave my resignation to the Prime Minister. I said, if you are going to go this way, then I am not able to, I think…

So, either follow your conviction and the path of reason or forget it.

But I must say that Mr Narasimha Rao backed me to the hilt, I think, in the first two years of our government.

Sir, there are those who say that this was like Dr Manmohan Singh’s re-education. He learnt and taught something else all his life. He was a socialist. And then when crisis came, he made a complete turnaround.

Well, let me say, I have always been a socialist in the sense that I regard a quest for equity, a quest for social equality as fundamental to running a modern economy and modern society. If by socialism you mean a passion for equity, a passion for equality, I am a socialist even then. But I have never been a socialist in the sense, in the doctrinaire sense of the term, that all things must be done by the government.

So, are you a socialist now or not?

I am a socialist in the sense that I worry about growing inequalities. I worry about the fact that millions of our children coming from poorer families are outside the school system. That millions of our families do not have access to safe drinking water.

So Dr Singh, what is it that this government is doing by the way of reform that you disagree with?

Well first of all, I do not agree with the way this government is handling the problems of the public sector. This is a government which, for its ideological reasons, wants to dismantle the public sector. Our view is, public sector should be allowed to grow if it can compete on an equal footing with private sector. Profit making public sector units, if they can compete, should be given every opportunity.

But shouldn’t they just become private? I mean, what’s the harm? Why shouldn’t the government run companies?

Because there is a distinction between private profit and public profit. When public sector companies make profit, those profits become, I think, assets for the Nation to expand further investments. Where are resources for education, for health going to come from?

Sir, what else do you disagree with?

Well, the other thing you say, although this government talks of deregulation but it is a case by case deregulation. There is no consistent hand moving with this…

Sometimes when your government was there, it was called ‘suitcase by suitcase’.

Well suitcase by suitcase, people ended up with the BJP.

Well that’s how politics is, isn’t it?

But, I will say if you ask me what’s the difference in our approach, our approach to deregulation is a principled approach. We would like a rule-based system, rule of law rather than a deal-based system.

Is that what you will do, if you come to power?

Yes, of course!

Are we going to see much more institutionalised reform, deregulation, privatisation?

Exactly, exactly.

You are still committed to all that?

Yes, of course we are.

Congress party is not making an about turn yet again on economics?

No, no.

Just because BJP took credit for reform…

No, the BJP never believed in reform. In 1996 and 1998, they came with the slogan that India is to be built by Indians. Their charge against us was that we were selling India to foreigners. Now, you look at it. I think the other day the finance minister announced private sector banking up to 74 percent of foreign equity. Now this is not what the BJP fought its election on. It fought its election on so-called Swadeshi. Now it is doing something which is totally different.

That’s what politics is. You say one thing but do quite another, isn’t it?

But I think you can’t carry this process beyond a certain point. You must, I think, carry conviction with the people that you are sincere, that you have thought through the problems of this country.

Otherwise, social and economic change in a country of India’s complexity, of India’s diversity, cannot be carried forward in a meaningful way.

Is there anything this government is doing that you not only agree with but you endorse? It may be peace with Pakistan or China. It may be economic reform.

First of all, as far as peace with Pakistan is concerned, our party has had a structured approach. We have always been in favour of talks with Pakistan. Even at the height of the Kargil war, we were in favour of talks with Pakistan.

Whereas, what is the consistency of this policy? The prime minister one day talks of our power. The other day, he mobilises a million people, then suddenly there’s a change and he goes to Jammu and Kashmir, he says ‘insaniyat’. There has been no consistent hand as far as this government is concerned.

Sir, what is it that this government has done that you endorse? Tell me one or two things.

Well, I think one thing I would say, for example, the National Road Programme…

The National Highway Programme…

Also, I would say the fact that although they came to power under the slogan of Swadeshi, I think they have, over a period of time, not dismantled the reform structure that we had set up.

And on that you seek consistency if there is a change of government in the next election?

How can we be sure? How does one know tomorrow the RSS, for example, would allow the government…

Well, that is what you are saying. If NDA comes back to power, RSS may block it. But if you come to power, you will not reverse it.

We will not reverse it. When I became finance minister, I said, we are going to produce a model of adjustment and structural change with a human face. And I said, we will show to the world that there is a humane way of dealing with problems.

So, if your party or your coalition was to come to power, are you promising us even better and even faster reforms?

Of course. Reforms which will address the problems of poverty. Reforms which will address the problems of our farmers. Reforms which will address the problems of our working classes.

Right. So, what is it that will change in the current scheme of things, if you come to power? Are you going to stop privatisation of the public sector?

We will not stop privatisation of loss-making public sector units. But public sector units which are doing well, which can compete against the private sector, both domestic and foreign, we will give them all opportunities to expand. But that doesn’t mean that these public sector enterprises cannot disinvest. If they want to raise money in the capital market, we allow them to do so.

But the government will not give up control. And the same would apply to nationalised banks also…

Well, we are against a system where the banking system will be entirely in the private sector. The Congress government nationalised the banking system. We would like the Indian banking system to remain 51 percent in the hands of the Indian government.

Sir, we talked about the change that you saw, from socialist economics to economics of the ’90s and then onwards, and what you’re talking about now. But tell me also about the re-education of Dr Manmohan Singh in politics. From academia to politics. I’m sorry to be asking this in the library of Delhi School of Economics, but…

No, no, when I came to politics, I thought, this is an opportunity for me to convert good economics into good politics. That has been my effort. But I have come to realise that politics, after all, is the art of the possible. And sometimes you have, therefore, to make compromises. Also, I came to politics with the belief that we must have a long-term vision, that we must look at India’s problem from a long-term perspective. But I have come to realise in politics, a week is sometimes too long a period of time.

And economics works in five-year plans and so on. But, sir, it’s always said that good economics doesn’t make for good politics. Do you think it still is true, or do you think it should continue to be true?

No, no, ref We have to create more wealth, we have to distribute that wealth equitably.

Also read: Marxism is a creative science—what CPIM’s Sitaram Yechury said on communism, coalition politics

Tell me something. You’ve worked with many leaders in India, leaders of the Congress party. As a party man, as well as a civil servant, as an economic adviser, how do you compare Sonia Gandhi with Narasimha Rao and Rajiv or Mrs Gandhi before that?

Well, of course, Mrs Indira Gandhi was the most stubborn personality. I think I have worked very closely with Mrs Gandhi. I’ve worked very closely with Rajivji. I’ve worked very closely with Narasimha Raoji. Now, each one of them, I think, were men and women of exceptional ability, character and convictions. And they have served India with great distinction. Soniaji, I think, she’s new to politics, but in the last five-six years that she has been the leader of our party, she has given the party a lead which has helped to unify our people.

What is a brief from her to you? What are you to achieve for the Congress Party and for her in this campaign and beyond?

A progressive, expanding economy and socially just politics.

Because we somehow don’t identify you with the din and dust of elections. Are you going to campaign?

Well, I should campaign. I’m a member of the Congress party, and I will be campaigning.

And are you going to contest?

Well, that I have not made up my mind.

But, you know, Pramod Mahajan has an interesting term—a ‘winnable candidate’. In some sense, you’re not a winnable candidate, because you did so much for the middle class in India, and yet South Delhi defeated you. The middle class is so ungrateful.

Well I have no…I think regrets and I am not putting the blame on the middle class. Maybe, there was some defect in me.

But are you game, if you are asked to contest again? Or do you think that is not for you?

Well, I have not made up my mind.

But you’re going to campaign from the front?

Well, of course, of course I should.

But, you know, that is the difference between a politician and an academic. There must be areas where you disagree with your party.

Well, I think when you are a member of a party, you have to abide with the party discipline. But I think that also means that there are areas where sometimes you have to accept the party decision, even when you feel that’s not the right decision.

Right. But at the same time, you think that you will have sufficient sort of moral and intellectual strength to keep the party in the right direction, whether it wins the election or not, in terms of having a sensible view on economic reform and…

I think there is no doubt about it. The Congress party, under Mrs Sonia Gandhi, in the last five years, has stood by the reform. There are important reform programmes, like, let us say, opening up the insurance system. It would not have been possible but for the support of the Congress party. The new electricity bill, which is a reform-oriented bill, would not have been passed but for the support of the Congress party.

The Congress party’s record is that when reforms are in the interest of our nation, we have backed that reform.

So whether the Congress wins or loses, nobody should see any threat to the larger reform process in India. You think that has come to stay?

Of course.

As a citizen, investor, taxpayer, I should have no insecurities?

Let me say that we are the original reformers, we are better reformers, and our commitment to reforms with the human face, to work towards a new India, free from the fear of war, want and exploitation, there should be no doubt about our total commitment to that goal.

Sir, on that note, I wish you all the very best in the coming campaign and I hope our politics sees the kind of reform that our economy has seen over the past decade.

Thank you very much.

For that to happen, you have to be around in front.

Thank you so much.

Also read: Why Manmohan Singh was late to his swearing-in ceremony in 1991