New Delhi: Main Hoon Ek Paheli Bhi (I Too Am A Riddle), a 1934 poem written by Mahadevi Verma, best represents the slippery slope one encounters while trying to understand the poet who was one of the four pillars of Chhayavaad– the neo-romantic movement of Hindi literature.

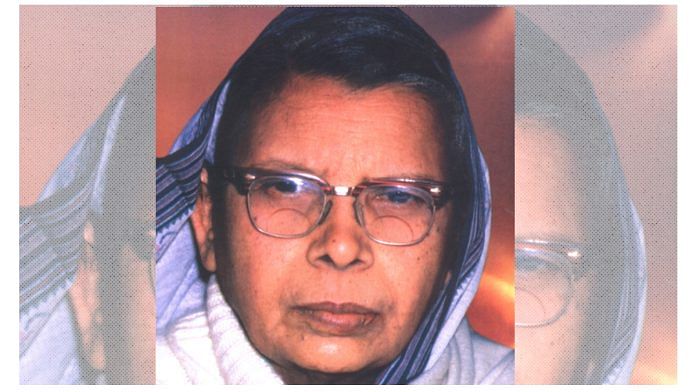

Author and veteran journalist Mrinal Pande remembers Verma as a dignified woman who wore only khadi saris and had her head covered at all times. She had an uncharacteristically “masculine” voice and was by no means “demure”.

Many compared Verma to 16th century Bhakti Saint and Hindu mystic poet Mirabai, and referred to her as “Modern Mira”.

Some have also called her a contemporary of French feminist writer Simone de Beauvoir, drawing parallels between her collection of 11 radical essays titled Shrinkhala Ki Kadiyan (Links In My Chain, 1942) and Beauvoir’s seminal text, The Second Sex (1949).

However, such comparisons do not begin to encompass the enormity and complexity of Verma’s life as a feminist poet, novelist, essayist, educator, editor and freedom fighter who wrote extensively on “the woman’s question”.

She refused to be married off

Mahadevi Verma was born in a progressive household, one that encouraged her to study at a time when women’s education was an anomaly. It is believed that her father prayed to Durga to be blessed with a girl, and soon the welcomed their daughter on 26 March, 1907 in Allahabad.

Verma’s father was an agnostic, Western-educated English school teacher and wanted Verma to be fluent in Urdu and Farsi. Her mother, a Hindu traditionalist from Jabalpur, was the one who instilled a love for Sanskrit and Hindi in her. She taught Verma the Panchatantra tales and introduced her to Mirabai’s poetry.

Verma was only nine years old when it was decided that she would be married off to Swarup Narain Verma, a boy from Bareilly. She was tutored at home and then sent to Crosthwaite Girls College in Allahabad, till she came of age.

The famous friendship between Verma and her inspiration, poet Subhadra Kumari Chauhan, began in Crosthwaite. The latter encouraged her to write in Khari Boli.

After graduating from college, Verma refused to fulfill her marital obligations and instead chose to live an ascetic life.

‘Don’t worry about men, just carry on writing’

Verma was the principal of Prayag Mahila Vidyapeeth, a girl’s school in Allahabad and became an active member of the freedom movement. She also served as an editor at Chand, a progressive magazine known for its dedication to social issues and its celebration of a hybridised and inclusive idea of the Hindi language.

Verma was often dismissed as a woman who only wrote about sorrow even though she was widely respected because of her proximity to Gandhi, Nehru and the poet Narela. Verma, however, was much too aware of the loneliness of a woman who lived a creative life and was unrelenting in her commitment to her craft.

Mrinal Pande told ThePrint about one of Verma’s visits to her mother Gaura Pant, the Padma Shri recipient writer whose literary name was ‘Shivani’. “Don’t worry about men, just carry on writing,” she said to Pant.

“Never become a legend, because then they will never read you,” she further warned.

Verma’s multi-layered personality

Pande recounted two particular incidents that describe Verma’s layered personality. Once, as part of a prize awarded to her in Indore, Verma was given 21,000 silver coins. Gandhi, who was part of the ceremony, went up to Verma and asked her to donate the entire amount, along with the silver katora (bowl) it came in, to the Swaraj fund. Verma agreed without any hesitation, but in turn, requested him to attend the kavi sammelan (poets’ conference) she was organizing. Gandhi claimed he had no understanding of poetry and refused, but Verma never forgave him and wrote about the incident years later.

Another time, during a lesson with her Buddhist guru, she realised he was hiding his face from her with a palm leaf. Shocked, she walked out and later said that someone who could not trust himself had nothing to teach her.

“She saw misogyny of all kinds, even from the greatest,” said Pande.

A feminist legacy yet to be discovered

Even though Verma was spiritual and believed in the Buddhist philosophy, she wrote about concrete issues of politics, social reform and women’s issues.

Anita Anatharam’s book Mahadevi Varma: Political Essays on Women, Culture, and Nation, points out that Verma’s essay Hindu Stri Ka Patnitva (The Wifehood of Hindu Women) suggested that marriage was akin to slavery. With no political or financial authority, she said, women were relegated to lives of being wives and mothers.

“If we can bear the harsh truth, we would have to accept it with humility: that society has given to woman the most debased means for building up her life. She must live, having been made a means for the exhibition and enjoyment of man’s wealth,” Verma writes.

In another essay, Ghar Aur Bahar (Home and The World), she writes, “As soon as [women] are married, the dreams of a happy home life become handcuffs and chains and grip their hands and feet in such a way that the flow of the life-force stops within them.”

Through poems like Cha, she explored themes of female sexuality, and with short stories like Bibia, she took readers into the world of women who experienced physical and mental abuse.

According to Pande, re-reading Shrinkhala Ki Kadiyahas opened her up to many radical ideas that are still relevant.

Mahadevi Verma died on 11 September, 1987 leaving behind a huge body of work that still requires critical feminist engagement.

Also read: Lala Amarnath, the shining light of early Indian cricket who transcended borders