Mangala Narlikar’s life was a quiet revolution—lived not in headlines, but in lecture halls, textbooks, and living rooms across India. A brilliant mathematician whose career spanned the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Cambridge, and Pune University, Narlikar balanced number theory and nursery rhymes, research papers, and roti-making.

“I can only describe myself as a part-time scientist, if a pure mathematician can be called a scientist at all,” she wrote in a personal essay, A Career in Mathematics.

She made full-time contributions: from publishing acclaimed books in English and Marathi to transforming the school curriculum in Maharashtra, and teaching underprivileged girls that numbers could be friends, not foes. In a generation when women’s aspirations were often softened to fit domestic frames, Narlikar refused to choose between intellect and caregiving. She wove both into a lifelong pursuit of clarity, compassion, and quiet impact.

At 29, after years devoted to domestic life, she returned to Mumbai from England with a chance to revive her academic path.

“She was deeply aware of the underrepresentation of women in science,” said Somak Raychaudhury, Vice Chancellor and Professor of Physics at Ashoka University. “At Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA), we ran extensive outreach programs across districts—especially on Saturdays—with thousands of students from classes 9 and 11, including many from girls’ schools. She played a key role in shaping those efforts. I knew her closely for decades and witnessed her unwavering commitment to education and young minds.”

Finding space for science at home

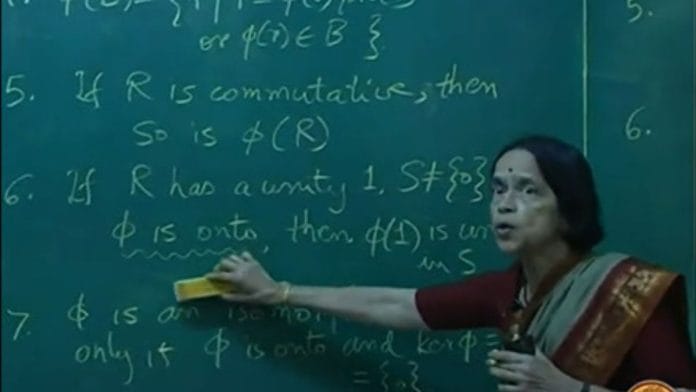

A gifted mathematician trained in number theory, algebra, topology, and analytic geometry, Mangala Narlikar built an extraordinary career while raising three daughters.

After completing her MA, she joined TIFR as a research associate. But almost immediately, societal norms reasserted themselves.

“Even while I was studying for the M.A., my family was pressing me to get married. Just after I was promoted, I got a good proposal and decided to accept it,” wrote Narlikar.

At 23, she married astrophysicist Jayant Narlikar and soon relocated to Cambridge, England, where he was working. There, she continued teaching undergraduate mathematics and attending lectures—but her research work came to a halt. Domestic responsibilities, social obligations, and two daughters quickly filled her days.

“My husband, a well-known astrophysicist, respected my wish to study mathematics although he too did not wish me to prioritise career over the family,” she wrote.

Returning to Mumbai in the early 1970s provided her with an unexpected break. The family moved into a house opposite TIFR, which allowed Narlikar to resume part-time academic work. She joined Prof. K. Ramachandra’s group in analytic number theory and earned her PhD in 1981.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Narlikar held guest lectureships at the University of Bombay and later taught at Savitribai Phule Pune University.

Her academic journey, though marked by part-time roles, was underscored by a determination to prove herself in a field where women were often underestimated.

Narlikar acknowledged that mathematics was a male-dominated field at the time, but she refused to accept the stereotype that girls were bad at math. She had consistently topped all her examinations, including in her final year at university.

Narlikar’s marriage to Jayant Narlikar was a true partnership built on shared values and mutual respect.

“Jayant and Mangala were so in sync that their support for each other was seamless,” said Raychaudhury. “Even when Jayant grew physically weak, she was always by his side—at lectures, in meetings—while managing the household, raising their children, and staying deeply committed to teaching. Her quiet strength was the foundation behind much of his work.”

Also read: Humble genius of IISc prof Madhavi Latha, who helped anchor world’s highest single-arch rail bridge

Math for everyone

If the first part of Narlikar’s life was about persistence, the second was about impact. In Pune, she focused on making mathematics less intimidating for the next generation.

She served as a part-time faculty member at Pune University and later as a textbook reformer and trustee at the Bhaskaracharya Pratishthan. Her work with Maharashtra’s Balbharati textbook board resulted in more accessible and engaging school curricula.

Narlikar began by tutoring the children of her domestic worker, eventually joining an NGO to teach math to girls in slum communities.

Realising her gift for making complex ideas simple and fun, she proposed changes to Maharashtra’s Balbharati (State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research) and soon became a key force in textbook reform. Appointed Chairperson of Balbharati in 2013, she introduced child-friendly features like visual aids, interactive problems, and even simplified number names in Marathi. Determined to keep learning accessible, she ensured her own books were priced at just Rs 10.

Mangala believed that math could and should be loved. But she recognised the barriers that made students fear it. Her later work centred on changing this dynamic.

She authored several books, including An Easy Access to Basic Mathematics and the award-winning Marathi title Gargi Ajun Jeevant Aahe. Her writing was rooted in clarity and empathy, aiming to reach those marginalised by elitist pedagogy.

Narlikar’s legacy took root not only in institutions but in her own home. All three of her daughters went on to pursue science and technology careers–one becoming a professor of biochemistry, the others researchers in computer science.

The mathematician died on 17 July 2023 after a long battle with cancer. Her life, often self-effacingly described as “part-time,” was anything but incomplete. She taught, wrote, raised daughters, supported her physicist husband, and touched generations of students.

“I missed being a full-time scientist. I did enjoy housekeeping, bringing up children and watching them grow, as well as sewing clothes for them, cooking, and travelling,” she wrote.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)