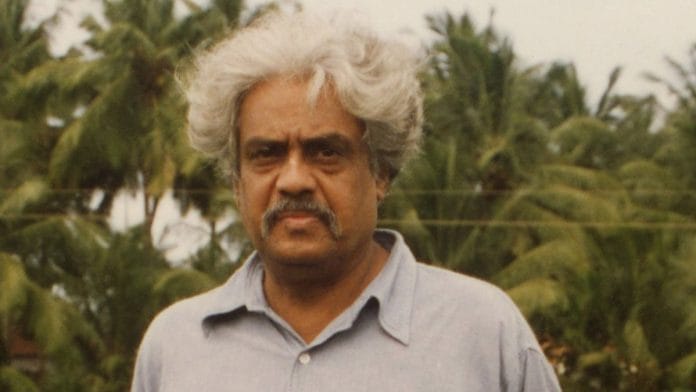

In 1940s Kerala, a young boy grew up surrounded by vast fields, where trees, flowers, and leaves of various shapes, sizes, and colours captivated his imagination. His childhood home may be a memory now but it lives in Achutan Ramachandran Nair’s paintings.

“Kerala of those times was not conducive to an artist like me,” he often said. “Malayali people appreciate verbal art. If you show them a painting, they’ll look at it for a while and then ask what it means. In Kerala, you either paint like Raja Ravi Varma or you’re not considered an artist.”

Ramachandran’s first encounter with art, as he recalled, was drawing a portrait of his 70-year-old domestic worker as a child. Unlike other family members, his mother encouraged his interest, bringing him clay to play with.

“I was more inspired by traditional murals than Ravi Varma,” he said in an interview in 2015. He considered Ravi Varma’s art to be more influenced by European portraiture.

Driven by passion and drawn to the works of Ramkinkar Baij, he made his way to Santiniketan, where Baij taught sculpting. Ramachandran arrived at Santiniketan at a time when it was not just an art school, but a way of life. He later said that this was the kind of art education he believed in. “Everyone does everything,” he said.

In an interview in 2021, he recalled that at Santiniketan they were taught various subjects—painting, theatre design, makeup, and sculpture. “They teach you how to live beautifully,” he said. “I joined Shantiniketan as a student and then continued as a researcher.”

Ramachandran’s body of work was informed by the political and social upheaval of the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s. Author and art historianRitika Kochhar described him as an indomitable force. “You can find Ramachandran in all his work.”

Move to Delhi and professional art

From designing his own house to crafting his workspace, Ramachandran always sought to mould his own space. He earned his master’s degree in Malayalam literature before moving to Kolkata in 1961 where he received a diploma in fine arts and crafts at Kala Bhavana, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan.

By the mid-1960s, Ramachandran had relocated to New Delhi, where he joined Jamia Millia Islamia University as a lecturer in art education. It was in Delhi that he was introduced to the professional art world. The 1960s saw an art market frequented by foreign buyers but geopolitical tensions, including the India-Pakistan war, led to a decline in foreign collectors, affecting the market, he recalled.

Ramachandran’s early works from this era reflected engagement with urban anxiety and socio-political unrest. Influenced by expressionism, his large canvases were filled with stark, powerful imagery—depictions of human suffering and dehumanisation.

A shift could be seen in his art in the 1980s after a visit to Rajasthan. There, he was introduced to the vibrant traditions of tribal communities, whose deep connection to nature and colour-rich aesthetics left a lasting impact on Ramachandran’s work. He moved away from the sombre themes of the 1960s toward art that celebrated life, mythology, and the natural world.

“Every year, Ramachandran would visit Udaipur and its villages,” R Siva Kumar, art historian and curator, wrote in The Indian Express.

Also read: Laxmikant Berde could never break out of the comedy mould. The audience kept him trapped

Beyond painting

Ramachandran didn’t limit himself to the canvas. His intricate bronze sculptures echoed the themes of his paintings. His ability to translate the dynamism of his canvases into three-dimensional forms was particularly evident in monumental works like the granite bas-relief sculpture at the Rajiv Gandhi Memorial in Sriperumbudur, Tamil Nadu. It was completed in 2003—stretching 125 feet in length and nearly 20 feet in height.

One of Ramachandran’s most ambitious works was Yayati, a reinterpretation of a Mahabharata tale, designed as the inner shrine of a Kerala temple. The installation featured 13 bronze sculptures surrounded on three sides by painted murals, covering an impressive 60 by 8 feet where he weaved mythology, history, and tradition into a contemporary visual language.

Beyond gallery spaces, Ramachandran made a significant mark in public and international art. He illustrated a children’s book published by Fukuinkan Shoten Publishers in Japan, with one of his books becoming part of the nursery school syllabus there. His works found homes in prestigious institutions worldwide, including the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi, the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, and galleries across the US, Japan, and Singapore.

In recognition of his contributions to art, Ramachandran was honoured with numerous accolades. In 2002, he was elected a fellow of the Lalit Kala Akademi, and in 2005, he was awarded the Padma Bhushan, India’s third-highest civilian honour. He died on 10 February 2024.

Art as political commentary

Though much of Ramachandran’s work featured expressionist watercolours, certain pieces—such as Kali Puja, inspired by the Naxal movement in Kolkata, and End of the Yadavas, which intertwined themes from the Mahabharata, the Polish gas chambers, and the devastation of the atomic bombings—were stark depictions of human violence.

Ramachandran attributed these dark themes to his early influences, including reading Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky and witnessing poverty living in Kolkata. Recalling a striking contrast, he described the living conditions of Tamil Nadu labourers in the city, saying, “I saw a man in a gutter drinking muddy water.” In comparison, he noted, life in Kerala seemed different. “Even beggars there are neatly dressed and wear clean shirts.”

“I was young and rebellious,” he recalled in an interview with Ella Dutta. “Coming from Kerala, from a background like mine,” he said he was uncomfortable looking at things that were “socially” incorrect, things that were “wrong towards other humans.”

In a 2015 interview, the artist himself reflected on his evolution, stating that while he started as an “angry young man” creating socially charged art, he later realised that art transcends social commentary. And this was reflected in his work.

“They [the viewer] already have enough miseries in their lives—I need not add to them. I don’t need to remind them of their suffering from morning till night. And ultimately, what I create is something I can sell,” he told Open Magazine.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)