New Delhi: “He never left you with a feeling of awe. Awe creates distance. He leaves you with a feeling of a friend touching you, a beloved touching you,” says Mahesh Bhatt, in the 2016 documentary film Kagaz Ki Kashti, by Brahmanand S. Siingh that explores the journey of Jagjit Singh from a young boy in Punjab to an internationally acclaimed musician.

Singh’s instantly recognisable deep voice, the tune of Tum Itna Jo Muskura Rahe Ho, and his simple kurta-clad, bespectacled persona are forever etched in the memories of millions, irrespective of what generation, religion, region or class they belonged to.

From Punjab to Mumbai to the world

Singh was an immensely revered musician. Receiving the Padma Bhushan in 2003, and being honoured with a commemorative stamp after his death in 2011 by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh is a testament to that. But his journey to that point is peppered with various instances that strengthened him as an artist.

Having grown up in Sri Ganganagar in the Punjab-Haryana border, singing kirtans, he developed a spiritual connection with music at a young age. His father was a PWD engineer who had always harboured a love for music, and to nurture his youngest son’s talent he found him a music teacher — Ustaad Jamal Khan.

Singh carried this training and passion to college — he began to perform in college festivals while at Punjab University and soon became his college’s pride. He even enjoyed the benefit of his fee being waived. In Kaagaz Ki Kashti, he recounts one particular performance through which he got his first “taste of success” — an overwhelmingly long applause along with a cumulative amount of Rs 125 from the audience, all the way back in 1956.

His father was keen on him becoming an IAS officer, but he insisted on doing what he loved and set off to Bombay by himself in 1965. Conscious of being dismissed as a Sardar who could only sing Punjabi songs, he cut his hair and shaved his beard — a highly unorthodox move at the time.

Bombay for him represented years of struggle, even though he did occasional gigs, jingles, radio and TV commercials, including a notable one for Dalda ghee. At one point, he even had a stint as a party singer for the film industry, mingling with the likes of Rajesh Khanna.

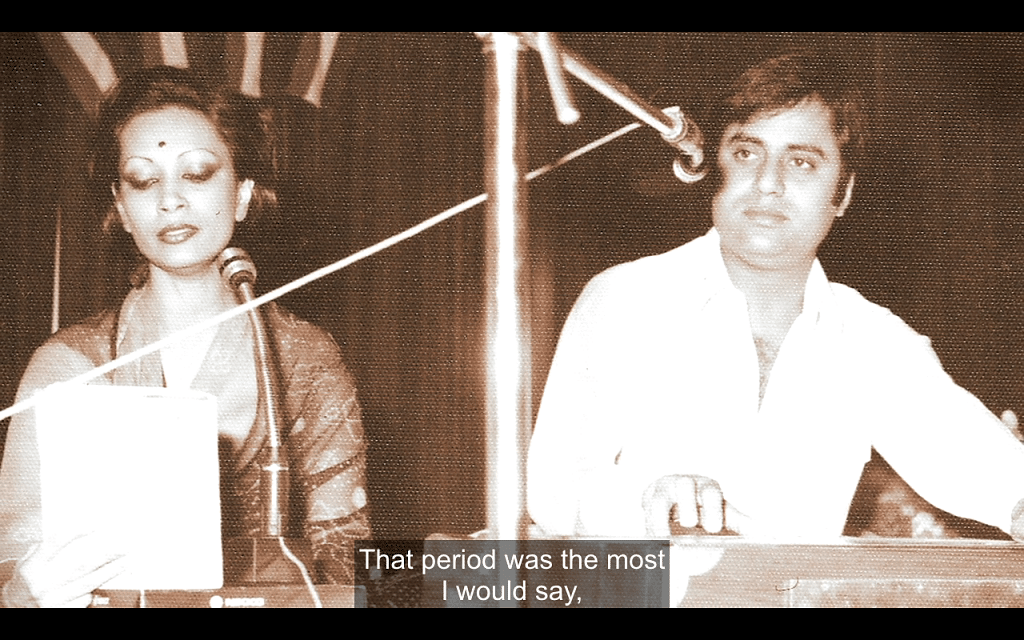

He eventually met singer Chitra Dutta, who first became his musical collaborator and then his wife. Audiences doted on the duo who had polar opposites characteristics — his heavy bass voice in contrast to her trill tone, his gregarious personality versus her quiet demeanour, his Punjabi charm complementing her classic Bengali beauty.

Together they built a family, a musical community, recorded several successful albums, and extensively toured the world — from East Africa to the West Indies, from Canada to New York. When they performed at the Royal Albert Hall, London, in 1982 it was the go-to event for the South Asian communities living there.

Once Singh established himself as an unparalleled performer and recording artist, he finally made his foray into Bollywood with Mahesh Bhatt’s Arth (1982), his melancholic verse suiting perfectly the complex extramarital relationship drama starring Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil and Kulbhushan Kharbanda.

In 1990, Jagjit Singh and his wife suffered a tragedy when they lost their son in a bike accident. Chitra gave up singing and retreated from the public eye and many felt Singh, who did return to singing after a year, was never the same. But he became a philanthropist, supporting multiple organisations such as CRY and Save The Children. He continued to perform while exploring devotional music, and channelled his sorrow into intensely emotional verses that are heartbreaking, even today.

He continued to work in Hindi films right until the early 2000s. Some of his notable movie songs include Tum Ko Dekha To Yeh Khayal Aaya (Saath Saath, 1982), Chitthi Na Koi Sandesh (Dushman, 1998), Hoshwalon Ko Khabar Kya (Sarfarosh, 1999) and Badi Nazuk Hai (Joggers Park, 2003).

Revolutionising ghazals

With the words, “Toh, doston” (So, friends), Singh started each of his live performances by putting his audience members at ease before enthralling them with his enchanting voice and soulful lyrics. As a ghazal musician, his project was first and foremost to make the dying art form accessible to all. He shunned the traditional hierarchy of Ustads and Gurus in classical music, and always donned the persona of a relatable human being, regardless of how famous he eventually became. He was hugely responsible for mainstreaming ghazals post the 1980s, as the genre had earlier been relegated to narrow audiences who followed the work of old stalwarts like Begum Akhtar and Mehdi Hassan.

During an episode of Aap Ki Adalat, host Rajat Sharma tried to provoke Singh saying that if Begum Akhtar were alive she would be aghast at his music, alleging that he had compromised the “purity” of ghazal music. “Thank god, she’s not here,” Singh joked in return, explaining that he had not disturbed the purity of ghazals as an Urdu poetry format but had changed how it was sung. Unafraid to experiment with musical arrangements like adding choruses and western instruments such as the guitar and violin, and the harmonium (an offshoot of the accordion), he argued that it was all music that made the same swar (notes) as Indian instruments at the end of the day.

Also read: Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew, the freedom fighter who is hailed as the hero of Jallianwala Bagh