Before food influencers and celebrity chefs, there was Imtiaz Qureshi. As fast-food chains were opening up in India, he went the other way. He brought back copper vessels and dum pukht, the slow cooking technique of the Mughal courts. While restaurant-goers were happy binging on butter chicken, he made Awadhi biryani something to splurge on.

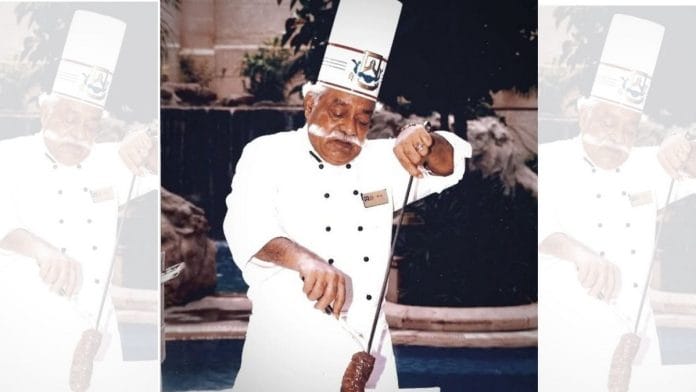

He started out cooking halwa-puri and boiling eggs for British soldiers and went on to win the Padma Shri for his contribution to Indian cuisine. As the ‘Grand Master Chef’ of ITC Hotels, he was synonymous with the restaurants Bukhara and Dum Pukht. He died on 16 February last year at 93, but to the many chefs and diners who looked up to him, he’s still ‘Ustad’.

“He was a larger-than-life figure and immensely proud of his cooking. He was his greatest ambassador. He was perhaps the first chef (from a catering business background) who acted like a superstar, who brought respect to the profession,” said journalist and food writer Vir Sanghvi, founder of the culinary platform Culinary Culture.

Qureshi showed his mettle from a young age. When he was an apprentice at a Lucknow catering service, he salvaged a grand feast ghazal queen Begum Akhtar was hosting. When the head chef failed to turn up, the teenager conjured up the meal exactly how Akhtar wanted it.

“For about 8-10 years, I worked hard, often for free. I’d spend entire days around tandoors, learning the craft. Whenever there was a party with biryani, I’d follow the caterers just to observe and learn,” he recalled in a 2020 TEDx Talk.

Over the years, his food would reach prime ministers and presidents—Jawaharlal Nehru, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and Zakir Husain to Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, to name a few. But the most lasting part of his legacy was bringing back dum pukht, a technique from royal kitchens that was slowly fading into obscurity.

“The dum pukht style of cooking gently coaxes out the maximum flavour from ingredients and spices. The result is a delicious cuisine which has now become deservedly mainstream with items going beyond traditional meat to vegetarian dishes too. Chef Ismail Qureshi needs to be lauded for reviving and championing this traditional technique, associated with Awadh,” said food historian Rana Safvi.

Also Read: Malayali artist A Ramachandran saw poverty for the first time in Kolkata. It changed his art

Nawabi roots to impressing Naoroji and Nehru

Food was in Imtiaz Qureshi’s blood. Born on 2 February 1931 in Lucknow, he came from a family of cooks who had served the nawabs. A burly young man with a passion for wrestling, he was always an artist with food.

He started his culinary journey with his uncle as a nine-year-old. By 12 or 13, he’d later claim, he was already impressing diners at the Parsi Club—including Dadabhai Naoroji—with his biryani.

When Qureshi was 16, his uncle was tasked with preparing food for 10,000 British soldiers—without electricity, cooking ranges, or modern equipment.

“Kaam toh ustad ka tha, par sambhalna hamara (it was the ustad’s work, but my job was to manage everything)” he recalled in a 2016 interview.

He briefly branched out into his own catering business, but his mother insisted he not compete with his uncle, he said in his TEDx Talk. Instead, he joined Krishna Caterers.

His experience with large-scale cooking proved useful when Krishna Caterers was given the job of feeding soldiers in Lucknow during the 1962 India-China war. But logistics wasn’t the only challenge—Hindu and Muslim soldiers refused to eat food prepared by cooks from the other community. Eventually Nehru himself visited the camp to broker an understanding. This became Qureshi’s first link to the Nehru family, and one that would change his trajectory.

That same year, he cooked one of his most famous meals at a dinner hosted by politician Chandra Bhanu Gupta, attended by Nehru and President Zakir Husain.

The catch was it had to be vegetarian.

“I worked all night and much of the next day to craft vegetarian dishes that tasted like non-vegetarian. So, there was lauki qalia instead of fish qalia, jackfruit musallam instead of murg musallam, lotus stem kebab in place of shammi kebab,” recounted Qureshi in 2014.

Nehru was so impressed that he hired Krishna Caterers for the opening of the Ashok Hotel in Delhi, setting Qureshi on a path that would change Indian fine dining.

ITC’s gamble & Awadhi revival

ITC Maurya’s Dal Bukhara is often credited to Imtiaz Qureshi, though this is hotly debated. But what is undisputed is what he did for Awadhi cuisine.

As Punjabi cooking became the face of North Indian food, kebabs were increasingly made in the tandoor. Qureshi, however, revived classic Awadhi cooking styles, including kakori kebabs, traditionally made over an open fire, and galouti kebabs, made on a tawa. It became such a rage that ITC Maurya opened Dum Pukht dedicated to it in 1987.

But his entry into the ITC conglomerate in 1979 was a stroke of pure luck.

The story goes that at a hotel in Aurangabad owned by PL Lamba of Kwality-Gaylord, a major trade conference was underway. Lamba brought in a young wedding caterer—Qureshi—to cook. Much like his previous brush with Nehru, Qureshi’s food impressed the guests. One of them happened to be Ajit Haksar, then head of ITC Hotels. He eventually tracked down Qureshi and hired him to showcase the best of Indian cooking at the Maurya.

“In the 80s and 90s, if you had saved up and were celebrating an occasion, you splurged on European or Chinese food. With Qureshi’s food, Indian food and restaurants became the choice for celebrations,” said Sanghvi.

Qureshi pushed back against convention from the start. He insisted on cooking in copper vessels, but the management refused to approve his request. He didn’t relent. After much back and forth, he finally bought vessels himself at Rs 20 per kg—and started what became a norm at the five-star hotel.

He also gave biryani an identity upgrade.

“Until he came along, biryani was a dish meant for masses of people. He made it a gourmet dish, cooked and served individually in sealed earthenware. He also changed the recipe of the classic Lucknow biryani, which they actually call pulao, by adding elements from Hyderabadi biryani. This is now copied by cheaper biryani places,” said Sanghvi.

Qureshi’s food became a talking point. He started featuring in ads for the restaurants operated by the ITC group. Even Taj Hotels tried to bring him on board, but he had already pledged loyalty to ITC.

“I created the menu for Bukhara in one night while running a 104 degree fever. Till date, the menu remains unchanged,” Qureshi told Mid-Day after being awarded the Padma Shri in 2016.

Also Read: Karnataka’s first woman engineer didn’t let anything thwart her PhD dream—even WW2

‘People will remember this’

Qureshi’s food turned ITC restaurants into destinations and young chefs saw him as the gold standard.

“As a Lucknow boy with dreams of becoming a chef, the folklore of Imtiaz Qureshi is something I grew up with,” wrote celebrity chef and actor Ranveer Brar in an Instagram post after Qureshi’s death last year. “It was around 1999 when I was working as a trainee chef at the Taj in Delhi. I remember once taking the Rs 3612/- I had earned for the month to ITC Maurya next door and trying out the Galouti Kebab.”

Qureshi’s fame made other chefs from his family sought after, not just in India but around the world. He mentored many from the younger generation, sharpening their skills and helping them spread the magic of Awadhi cooking. His eldest son, Ishtiyaque Qureshi, now runs Kakori House, a restaurant that honours the legacy of both his father and the Qureshi family.

“We look at Chef Qureshi as an idol who didn’t go through any culinary institution, and in spite of that, he revolutionised Indian cuisine. Even after 30-odd years, the menu of Bukhara has not changed,” said Nishant Choubey, consulting chef at Michelin Plated Indus Bangkok and co-founder of Street Storyss Bangalore.

In his 2020 TEDx Talk, Qureshi spoke proudly about his career, recalling his work across every aspect of cooking, from biryani to bakra musallam to the sweet dish zarda.

“While new trends come and go, we preserved the old, traditional dishes,” he said in Hindi. “I believe that in the times to come, people will remember this, and they will feel great joy in recalling it.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)