New Delhi: From the high defiles over the railway line, death had watched patiently, knowing its time would come. Early in October 1879, led by Lieutenant-Colonel James Gavin Lindsay, British engineers had begun to punch a railway line that was meant to link the plains of Sindh to Kandahar to sustain the northward push of the empire.

The first 214 kilometres had been completed by the New Year at an incredible rate of almost two kilometres a day. Then, at the town of Sibi—then just a cluster of squalid huts—the engineers paused to mass the materials needed to finally punch through the mountains towards Quetta.

Labourers now had to surmount the first of a series of tunnelling challenges that faced what had been named the Kandahar State Railway. The workers, mainly ethnic Pashtuns from Peshawar, used dynamite to blast their way through the rock, and then propped up the passages with Deodar and teak logs.

Then, in the summer of 1880, news came in of the annihilation of British forces at Maiwand. There was nowhere for the train-line to go. The construction party and its engineers began their long retreat to the plains. A single convoy of workers, though, was left exposed in the Kuchai defile. The Marri tribesmen, who had been waiting on the mountains above, now seized their opportunity to loot the workers’ equipment and money. Forty-two men were killed.

Hi, and welcome to this episode of ThePrint Explorer. Earlier this week, as you know, terrorists of the Balochistan Liberation Army’s Majeed Brigade hijacked the Jaffar Express, which makes the 34-hour journey from Quetta to Peshawar. There are still only hazy accounts of exactly what happened, and in one of the strange twists of history, the place where all this happened isn’t far from the site of that murderous attack in 1880.

There’s been a ton of excellent journalism and analysis in ThePrint on the BLA and the conflict in Balochistan. But today, I want to talk about the history of that railway line and why it matters.

The BLA has shown with this attack that it understands geopolitics and strategy. The Peshawar-Quetta railway line is a critical asset for Pakistani military logistics—as it was for the British before them—providing a reliable way to haul supplies and move personnel through the gorges and defiles of the Toba Kakar range over the Bolan Pass.

There is also a highway, sure, but—as imperial Britain understood—trains are efficient, fast and reliable. The real message the BLA has sent isn’t that it can kill people, but that it can choke Pakistan’s military presence north of the Bolan pass, and weaken its hold on the border with Afghanistan.

For India, there are lots of lessons to be learned from this story. The most important one, of course, is about the railway line to Kashmir, an engineering marvel that is nearing completion. The railway line will ease Indian military logistics, but also offers terrorists a target to hit.

Elsewhere in the country, too, terrorists have targeted trains. There were massacres on trains in Punjab back during the insurgency and Maoists have regularly tried to disrupt rail traffic.

These lessons, I’ll come back to later, but to understand them, we’ll have to first engage with the incredible story of the unfinished Kandahar railway itself.

Also Read: Why Trump’s bid to end China’s rare earth mineral monopoly may trigger a geopolitical headache

The rail to nowhere

A civil engineer who worked on that Kandahar railway line wrote…and forgive me for this long passage, but it bears listening to, I think:

“The line does not wind its way through smiling valleys to the breezy heights above, and then after a rush through an Alpine region, break out with mile upon mile of verdant plain, like the railways which lead from France and Germany to Northern Italy. On the contrary, it traverses a region of arid rock without a tree or bush, and with scarcely a blade of grass—a country on which nature has poured out all the climatic curses at its command.

In summer the lowlands are literally the hottest corner of the earth’s surface, the thermometer registering 124 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade, while cholera rages, although there is neither swamp nor jungle to provide it a lurking place. In winter the upper passes are filled with snow, and the temperature falls to 18 degrees below zero, rendering outdoor labour an impossibility.

The few inhabitants that the region possesses are thieves by nature and cut-throats by profession, and regard a stranger like a gamekeeper does a hawk—something to be bagged at all costs. Food there is none, and water is often absent for miles; timber and fuel are unknown, and, in a word, desolation writ large is graven on the face of the land.”

Why would someone build a railway line through such a place?

Following the Great Rebellion of 1857, Imperial Britain’s attentions were firmly focussed on internal security, particularly in the Gangetic plains, not expansion towards the North West. There were some strategists though, who called for the reversal of this policy, fearing a southward push by the Russian empire.

Egged on by the Viceroy Robert Lytton, Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli pushed for what was called a “Forward Policy”. In 1878, Lytton submitted an ultimatum to the Afghan emir Sher Ali, demanding that Russia be stopped from having a mission in Kabul.

There was, predictably, war. The war eventually ended in a British victory, when its defeat at Maiwand was reversed by a triumph in Kandahar. Lytton, however, came to understand the pointlessness—and gargantuan expense—of maintaining a permanent presence in Afghanistan. He chose to subcontract the responsibility to a new emir Abdul Rahman.

Liberal politicians, who ruled from 1880 to 1885, withdrew forces from Kandahar and garrisoned them in Pishin and Sibi. The Frontier Province, as it was known, was headquartered in Quetta.

Even though the effort to build the railway line had ended badly, there was no ignoring the expansion of Russian railways eastwards towards the Caspian, ever closer to Herat and Afghanistan. The Liberal government approved the resumption of a road construction project in 1883, discreetly called the Harnai Road Improvement Scheme—no reference to Kandahar or Afghanistan. Though carried out by military engineers, the project was executed by the Public Works Department.

To prevent any concerns rising in Afghanistan, a ban was placed on the use of railways to transport material, which made the road construction project a nightmare.

Led by Major-General James Browne, the Harnai project was staffed by three battalions of Pioneers, and five companies of the Bengal Sappers and Miners, together with thousands of Indian workers. One account described those workers as “the riff-raff and sweepings of other departments; for respectable natives would not go to a place with such an evil reputation, and good reliable men were not likely to be spared by their own masters.”

The historian Edward Spiers’ majestic book on the railway line has documented what was involved. From Sibi, about 91 metres above sea level, the line had to rise to 1,981 metres high at the Bolan Pass in a mere 193 km.

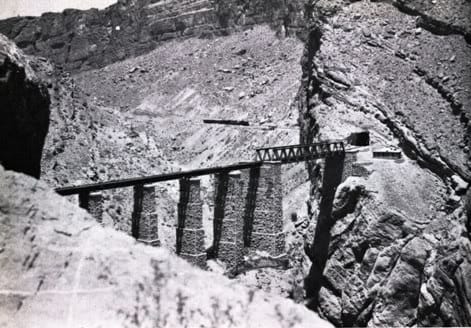

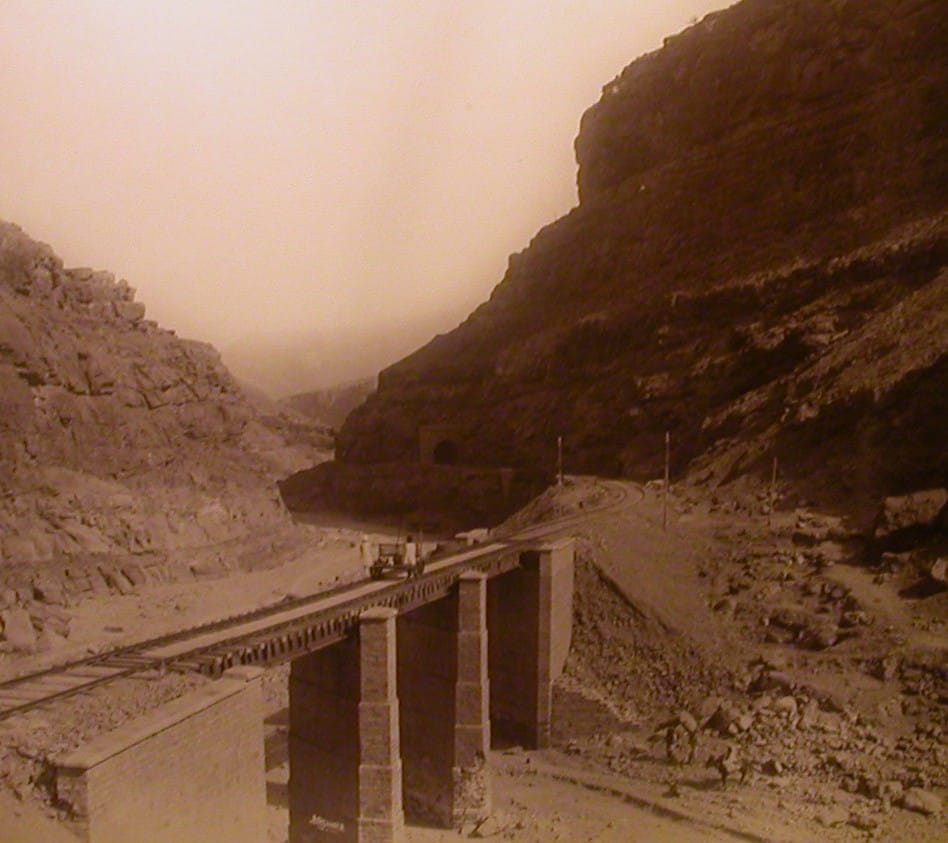

The engineers confronted incredible natural obstacles—The 22.5 km Nari gorge, through which the railway crossed the Nari River five times, and pursued a tortuous course round the bends of the gorge; the Gundankinduff Defile, requiring the construction of two tunnels in treacherous material; the spectacular Chappar Rift, a chasm 4.3 km long through which the line had to pass by way of nine tunnels with a collective length of almost two km; a viaduct 23 metres high and one large bridge 76 metres above the stream below; and the so-called ‘Mud Gorge’ on the summit of the Bolan pass—a narrow, winding and steeply sloping valley, 8 km long with a shale bed consisting mostly of gypsum and clay.

This material tended to swell and rise several feet after heavy rain, and then subside when it dried out.

In 1884, Russia annexed the emirate of Merv, and a concerned government in London turned the road project into a railway line again. To speed up construction, the line was laid initially along the bed of the Bolan river, which was subject to periodic flooding.

The first 64.4 km were fairly gentle, but then the route moved on to a much steeper incline, precluding the use of a broad gauge. Hirok, some 90 km from Rindli and 1,371 metres above sea level, became the changing station, where the narrow gauge line took the railroad over the summit of the pass, and back to broad gauge again.

Engines, carriages and wagons for the narrow-gauge section had to be brought up the mountains on the backs of elephants, images of which were reproduced in newspapers around the world. Thereafter, another changing station enabled the 40 km of remaining route to reach Quetta over a broad gauge along an almost level plain.

The entire project was rebuilt in 1884, requiring eight tunnels and four crossings of the river up the Mushkaf Valley, and three tunnels in the Bolan Valley. Near Kolpur, the engineers built nine bridges over the Bolan River.

Even tougher work was required to push the line from Sindh to Pishin. Fever and scurvy claimed hundreds of lives in the tunnel work in 1884. Following an outbreak of cholera, Pashtun workers deserted the project. To replace them, hundreds of masons and bricklayers from Delhi and eastern Punjab were brought in, and work continued battling floods and landslides.

The workers on the Rift, Spiers writes, had to be lowered in rope chairs from the cliff above, and then used steel crowbars to bore holes about a foot deep into the cliff face at points previously marked with whitewash. Once holes were bored and the crowbars inserted, platforms could be erected from which the rock-face could be dynamited.

In 1888, both railway lines to Quetta were operational, and an extension was built to the forward post at Chaman. From the proposed terminus at Chaman, Kandahar was just 125 km away. A splendid cantilever bridge at Sukkur, providing a direct crossing of the Indus River, was built as well.

Also Read: Will Trump finally revive post WWII plan for Europe to create its own military

The end of the line

The final bit of the line to Kandahar, though, would never be built. In 1890, Major-General Sir George White led an expedition to survey the routes through Zhob valley, but the Indian government stopped him from venturing north of the Kundar River, lest it alarm the Afghan regime.

The field force moved in three columns through territory that had become prone to tribal disturbances, for fear of attacks. The British were learning that this terrain was possible to conquer, but very difficult to subdue. Then, in 1893, Amir Abdur Rahman and Sir Mortimer Durand signed an agreement that established an Indo-Afghan border. The lands of the Chitral, Bajaur, Buner, Dir, Swat, the Khyber, Kurram and Waziristan now marked the limits of British territory.

For much of the 1890s, on to the 1930s, as the British fought a succession of tribal uprisings, the railway line would prove critical. The station at Nowshera on the line between Peshawar and Rawalpindi became a vital junction and railhead for several expeditions. To give just one example of the size of forces the railway line sustained, Major-General Robert Low’s Chitral expedition of 1895 needed 28,800 pack animals to sustain itself beyond Nowshera.

The Malakand Field Force of 1897, which involved the services of a certain journalist called Winston Churchill, was also enabled by the railway. Churchill later wrote of travelling by rail for five days from Bengaluru in “the worst of the heat”. He observed, “…large leather-lined Indian railway carriages deeply shuttered and blinded from the blistering sun, and kept fairly cool by a circular wheel of wet straw which one turned from time to time, were well adapted to the local conditions.”

Finally, the railway line from Rawalpindi to Khushal Garh on the banks of the Indus proved invaluable support for the largest operation of this period—the Tirah expedition of 1897–98. Writing from the base camp at Kohat, 51.5 km from the railhead, Colonel Henry D. Hutchinson described trains delivering “1500 to 2000 tons of stores daily” over several weeks in advance of the troops going into the unquiet region.

Unquiet geopolitics

We can only imagine what regional geopolitics might have looked like, had an independent Pakistan pursued the railway line to Kandahar that imperial Britain never built. The route would have enmeshed Afghanistan even deeper into Pakistan’s economy, and likely brought in large waves of economic investment, and settlers who would have transformed the demographic foundations of Baluchistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

The idea of such a railway line has periodically resurfaced, but Pakistan’s failure to confront jihadists in its north-west ensured there were never the enabling circumstances needed for such a mega project.

Today, China is pushing for the construction of a railway line from Herat to Kandhar, linking to existing routes through Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Iran. The new 735-kilometre railway line from Herat to Kandahar is exactly what the British feared the Czars would push through, threatening their hold on India.

Although Pakistan and China are now close allies, the fact is a railway line will significantly diminish Afghanistan’s dependence on Islamabad, and how that affects relations between the Islamic emirate of Afghanistan and Pakistan, which are already fraught today.

And then, there’s Balochistan itself.

Five insurgencies, political scientist Imtiaz Ali reminds us, have marked the course of the region’s troubled history. There were conflicts in 1948 and 1950, the first time over the disputed accession of Kalat to Pakistan, and then as a consequence of Balochistan’s incorporation into the single province of West Pakistan.

The 1960s saw a third wave of insurgent violence, which on one occasion is alleged to have led Pakistani forces to bombard a rural Eid congregation. A fourth round of insurgency broke out in 1972, just after the Bangladesh liberation war, and a fifth under General Pervez Musharraf in 2005.

The train hijacking demonstrates a point that was never made in any of those insurgencies—that Baloch groups have the capability to choke Pakistani military logistics, and make supplying troops north of the Bolan pass ever more expensive. This marks a new and dangerous escalation from Pakistan armed forces’ point of view.

For us in India, the lessons are obvious. Nation states might be the product of our imagination, but culture and emotion are not worth much without concrete and steel. The British empire sustained itself on its railways, and so its successor nation states.

Imagine an insurgency which had the power to cut the sole road link, which once ran between the plains of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir. It’s possible that the insurgents might well have seized the state. At the very least, it would have placed enormous additional burdens on India’s resources to garrison and protect the Line of Control. Today, that very nightmare confronts Pakistan.

India’s investments in roads and railways in Kashmir, and elsewhere along its borders, are at least as important as troops or fighting equipment.

That lesson, Pakistan failed to learn in its north-west. The price it now pays remains to be seen.

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)

Also Read: Exile of atheist poet Daud Haider shows Bangladesh wasn’t secular paradise even 50 years ago

Very nice article

I feel it is wrong to refer the Members of BLA as terrorists as done in this article. They may be having there own reasons for this act committed by them. Of course, killing of innocent lives is always condemnable. But the people protesting/fighting in Balochistan are being decimated by an oppressive regime which needs to be condemned by every peaceful living indians and people like us all over the world.

The railway network an abiding contribution of the British to the subcontinent.

What an excellent article. Indebted to the author.

Anything can be a geopolitical critical if terrorism of any form exists. That’s why the most important step in a democracy is to find political solution acceptable to majority.