New Delhi: Earlier this month, hours after Claudia Sheinbaum became the first woman president of Mexico, another young woman was shot dead 19 times as she walked home from her gym. Like Sheinbaum, Yolanda Sanchez was a pathbreaker in her own right, even if the world’s newspapers didn’t publish her name.

The first woman to become mayor of the small city of Cotija, west of the capital, she’s alleged to have been assassinated by the Jalisco New Generation drug cartel. Ever since she took office in 2021, organised crime groups seemed to have Sanchez in their gun sights. In 2023, she was kidnapped and terrorised by her captors for over three days.

The elections in Mexico were history-making, but not only because all the top candidates were women. They were also the most violent in the country’s history, leaving at least 37 candidates dead, and more than 828 non-lethal attacks were recorded.

Mexico gets little attention in India, which is kind of a pity. The country is a manufacturing powerhouse in its own right, providing a gateway to the US market for countries across the world. As you can see, Mexico is an important provider of hydrocarbons to India, and the two countries are now exploring a free trade agreement.

That’s not what this episode of the Print Explorer is about though. And welcome back, those of you who’ve been watching this show. Hearty welcome to those of you who are here for the first time.

Mexico is home, apart from a booming economy and fabulous culture, beautiful places, to a ferocious drug war which claims thousands of lives each year. According to official data, there were over 30,000 homicides in 2022. That’s some 25 per 100,000 population, the highest level in the world. The number of deaths, by the way, is more than India has ever lost in any year with all its insurgencies put together.

The cartels have succeeded in overwhelming the government in some places, taking over places like the city of Celaya. You can think of the drug cartels as a kind of industry even, according to a study by former police officer Rafael Pietro Corral, organised crime is the fifth largest employer in Mexico, providing livelihoods to almost 2,00,000 people.

So why is this important to security planners and citizens in India? Well, Mexico is a kind of prism to consider the many things that could go wrong for India if it doesn’t develop strong professional police forces and a robust rule of law framework. All of India’s many insurgencies, Maoist, ethnic, Islamist, whatever, can ultimately be reduced to just two things, a cause and a gun. The intention to do anything isn’t much use, whether you’re a Maoist or a Jihadist, if you don’t have the tools to act on that desire. And exactly the same thing is true of organised crime.

Money is just as much of a motivator, of course, as any set of abstract ideological beliefs. Among the few blessings of India’s relative poverty is that access to firearms has been limited. Guns are expensive. Even though plenty of weapons are available on India’s periphery in countries like Myanmar or Pakistan, Indian criminals just haven’t earned enough in the past to import these weapons on a large scale.

The heroin trade in Afghanistan and Myanmar has allowed insurgents and terrorists there to acquire massive quantities of guns by contrast, and we can see the consequence. That isn’t true of various disaffected or criminal groups in India.

Mexico is what happens when dirty money and guns collide and there’s a ton of data that suggests this is a real threat to India. Think of the increasingly sophisticated weapons organised crime groups in Punjab and Haryana have been using. Think of the large number of firearms injuries and deaths in the last communal riots that took place in northeast Delhi.

The scholar Yogesh Kumar has pointed to the growing numbers of unlicensed firearms recovered each year in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. That’s probably just the tip of the iceberg. Now imagine that those firearms at some point in the future aren’t just ‘kattas’ that will blow up in your hand and are instead reasonably sophisticated modern weapons. Could it happen? Possibly. Mexico teaches us may be it can happen far more easily than we think.

Also Read: How long-decayed insurgent groups are growing across Northeast as Manipur conflict drags on

Shoots of Poppy

In the Sierra Madre mountains in Mexico’s Sinaloa state, the journalist Ioan Grillo has written, villagers called drug traffickers ‘valiente’, the brave ones. The soldiers who are sent to fight traffickers on the other hand are referred to disdainfully as gauchos or hired servants.

Local ballads glorify well-known drug lords as benevolent godfathers showering money and self-respect on their communities as they battle a distant predatory government. If that sounds a bit like secessionists and the way some communities react to them in India, it’s because it is. The Robin Hood image, of course, isn’t the reality as Grillo writes. The cartel squads come bearing death not gifts. But it points us in the direction of the fact that these gangs in the mountains in Mexico have been around a long time and developed deep roots in communities there.

Late in the 19th century, scholars Thomas Murphy and Martin Rossi write, large numbers of Chinese immigrants left their country, escaping colonial wars and economic devastation in search of a new life in the US. In the 1880s though, the US slammed the door shut on large swathes of non-white immigration and immigrants from China began heading to Mexico to work there as labourers on the railway lines or in the mines. The use of opium was ubiquitous in China at the time and the immigrants brought with them the poppy seed and the know-how to grow the plant.

All criminal markets ultimately emerged as the consequence of government policies, and Mexico was no different. In 1914, the US passed the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act which for the first time choked importation of opium from Mexico. This created a black market and the Chinese growers were ideally placed to profit from it. The criminals of northwest Mexico were located close to the 2,000 mile border with the US, one that was pretty much impossible to police.

Sinaloa also boasted a large population of various kinds of bandits and displaced peasants who were easily tempted by the profit from smuggling. Pink opium poppies had grown in this part of the Sierra Madre since Chinese immigrants had come to work there. Thus, there was already a production base and a supply chain.

A 1916 US investigation of the drug trade reported that the Mexican syndicates even had political support. The then governor of Baja California is supposed to have helped the traffickers in return for political donations. In the US, distribution came to be owned by ethnic Chinese immigrants in the San Francisco area who often had ties of kinship in Mexico. Eventually, when the business got big enough, local people in Sinaloa just pushed the Chinese out.

Like all businesses, the drug cartels in Mexico were very sensitive to the nature of demand. When the 1960s counterculture created a big boom for marijuana, Mexican farmers in Jalisco, Michoacan, Guerrero and Oaxaca began producing the crop.

Among the many American entrepreneurs seeking this marijuana was a man called Boston George Jung, who was inspired by the movie ‘The Night of the Iguana’ (1964) to fly down to Puerto Vallarta to score pot. He was soon making upwards of a hundred thousand dollars a month, a lot of money in those days as it is today, flying the herb up in light aircraft into America before he was finally arrested with a case full of the stuff in Chicago.

Jung later went on to become a major cocaine smuggler whose life story provided the basis of the fantastic movie ‘Blow’ (2001). The autobiography of the legendary marijuana smuggler Howard Marks, which is called ‘Mr. Nice’ in memory of one of his many fake passports, makes clear that Mexico wasn’t the only place that profited from the booming demand for pot.

Marks tapped suppliers in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Thailand among other places. Today when marijuana has been legalised in much of the continental US as well as in Europe and is openly grown in some parts of America, it seems a bit ridiculous that you needed these transnational chains and criminality to sustain the business. In countries like India after all, various forms of both opium and marijuana had long been used recreationally and even for spiritual purposes. Though it’s not good for you, it’s no more harmful than a bunch of other legally available mind-altering drugs, notable among them alcohol.

President Richard Nixon, however, was locked in an ideologically driven war against American counterculture. He didn’t like the people who were hippies and opponents of the Vietnam War and he wanted to get back at them and at black Americans in the inner city by declaring war on drugs.

In 1969, Nixon ordered Operation Intercept in which agents began searching every single vehicle or pedestrian coming across the southern border from Mexico, while the US Army set up big mobile radar units between each post. Trucks and migrants backed up for miles. The main impact though was on the American economy where small businesses and agriculture which needed the low-wage labour, and the trucks going through started to hurt.

Operation Intercept had to be called off after just 17 days, making clear there was just no way to seal off the border. Then Mexico was pressured into cooperating with Operation Condor, a military-style enterprise which ran from 1976 to 1978. The US supplied Mexico with large amounts of military hardware including 39 Bell helicopters, 22 small aircraft and even an executive jet, while units sent out by the country’s government tried to eliminate drug trafficking by spraying fields with herbicide and basically executing large numbers of suspects, many in staged encounters.

Like Operation Intercept, Operation Condor backfired. It earned the US and Mexican governments the undying hatred of the mountain communities that were targeted. Worse, the production side of the business simply shifted to Colombia and cocaine grown in that country now joined the supply chain. The cartels for their part simply moved their operations to the city of Guadalajara. When the US cracked down on maritime shipments from Colombia, the land border into the US re-emerged as one of the most important routes for the drug business.

Now, it’s worth noting that pressures were mounted on a number of countries at that time and a few decades down the road in the mid-1980s, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was forced by President Ronald Reagan to sign on to the war of drugs and pass the Narcotics, Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act in India which criminalised many kinds of drug use which until then had been more or less dealt with in a relaxed fashion. There’s a separate story to be done about how the NDPS did nothing in India to end drug abuse but created a vicious cycle of corruption implicating police forces, but we’ll come to that another time.

Also Read: How Pakistan got the nuclear bomb & then walked away from a peace deal

The cartel wars

Early in the new millennium, the new cycle out of Mexico was dominated by stories of change.

In 2000, the reforming President Vicente Fox had unseated the corrupt Institutional Revolutionary Party which had held power for not three terms, 71 years. Zapatista peasant rebels and pipe smoking poetry reading leader Subcomandante Marcos were trying to make a revolution.

The real story though was mostly ignored. The number of drug-related homicides was surging driven by cartel violence. From 1,304 murders in 2004, the number grew to over 2,100 in 2006. By the time President Felipe Calderon took office that year 2006 and launched a national offensive against traffickers, homicides rocketed to 15,272. How do we account for this? You have a war on drugs but more people are getting killed than ever before.

Well, it turns out it’s pretty simple. First, it was a market worth fighting for. In spite of the hype around the war on drugs, it didn’t really achieve its intentions. Now cartels don’t share their balance sheets, but the market value of drugs trafficked from Mexico is estimated by various experts to have grown from a few million dollars in the 1970s, the marijuana era, to upwards of 40 billion dollars per annum in the new century. 40 billion.

Secondly, sophisticated weapons from the US had become available to the drug cartels in ever-growing numbers after America abolished restrictions on the sale of assault weapons in 2004. Between 2007 and 2011, Mexican security forces captured 99,000 guns. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, the relevant US government body, traced 68,000 of those 99,000 guns back to the US. In other words, a market had developed where the US was selling guns, kind of paying for the drugs that were coming in from Mexico. A kind of reciprocal balance of trade fixing equation, if you like.

The response of the governments of the US and Mexico was to try and mount even more coercive pressure. But this also backfired. By 2011, there were 96,000 soldiers and 16,000 Mexican marines in the campaign against the cartels. That’s more personnel, by the way, than India’s estimated to deploy in counter-insurgency operations in the Kashmir Valley. Military personnel, I should add.

The offensive focused on bringing down the kingpins, a technique known as decapitating the cartels by removing their heads, cutting off their heads. The Mexican government compiled a list of 37 key traffickers and 25 of them were arrested or shot dead by the time President Calderon left office.

But even though security forces had some big successes, once finding 23 tons of cocaine on a ship in the port of Manazil and recovering $2,007 million in cash, banknotes from a mansion in New York City, it did little good. The cartels had accommodated these losses in their pricing model, which the market in the US and Europe was happy to pay. There wasn’t enough work being done on demand control while people were locked up regularly.

The question and the social factors behind addiction and drug use weren’t being adequately dealt with. The decapitation strategy, moreover, created even more violence because each time a drug lord was killed, his lieutenants or rivals fought over succession and territory. For example, following the killing of Beltran Leyva in December 2009, the number of homicides in the state spiked from 259 in 2009 to 487 in 2010.

The most brutal figures ultimately survive and thrive in these situations. Oscar Garcia, a former Marine who worked as a hitman for Beltran Leyva, said he had personally carried out 300 murders after he was arrested in 2011.

Worst of all, the war on drugs did nothing to reduce drug trafficking, the problem it was meant to address. The total amount of drugs seized on the US southern border went up and up during President Calderon’s administration. In 2010, US agents seized 4.5 tons of crystal meth, 905 kilograms of heroin, 1,500 tons of marijuana and 17.8 tons of cocaine. This was comparable to 2.7 tons of meth, 449 kilos of heroin, 1,046 tons of marijuana, and 27 tons of cocaine in 2006.

Now, why, you might understandably ask, are rising seizures a bad thing? Catching more drugs should be a good thing, right? But drugs were still available to the market. The US government, public health professionals, anyone concerned with this knew that anyone who wanted to score and buy drugs could, which meant the seizures were actually a proportion of the actual volume of trading. In other words, there were more and more drugs coming in, a percentage of those was getting seized, and a bigger percentage was getting through.

A grim future

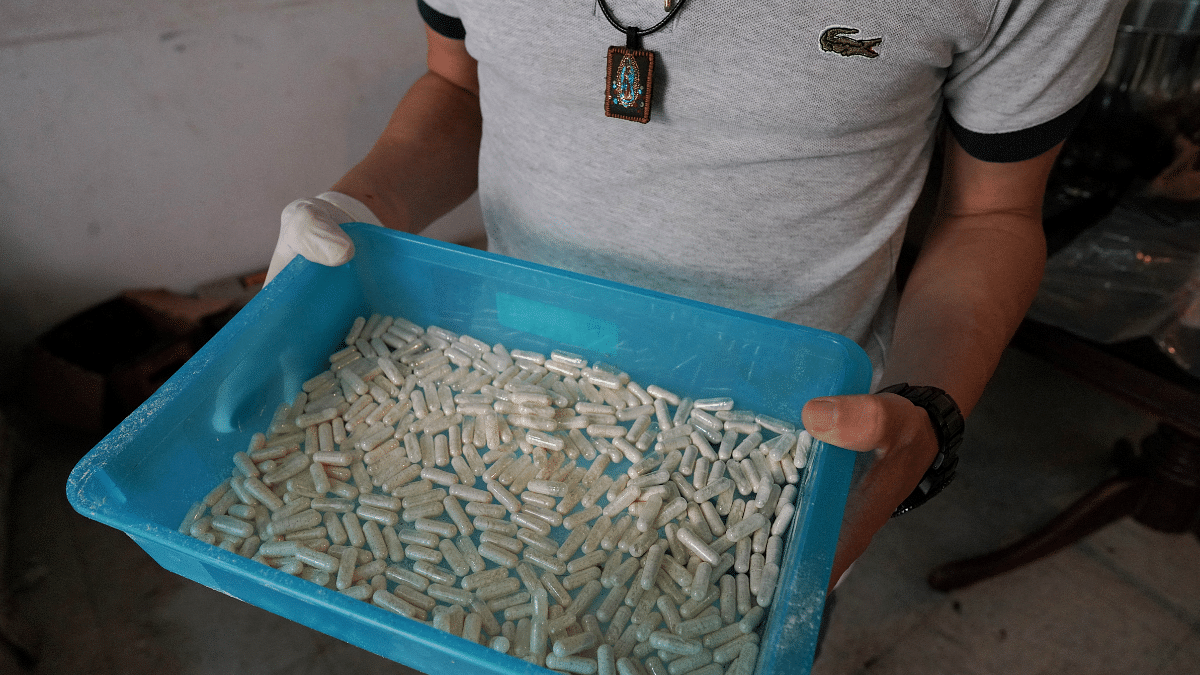

Where do things stand now? For one, despite the bloody war in Mexico, Mexican cartels are doing really well integrating themselves inside a global market system. The big growth area are synthetic narcotics like methamphetamines or crystal meth.

Beyond bases in Sinaloa’s Culiacan and Lazaro Cardenas, one of the major transit places for precursors, Chinese criminal cartels are believed to have set up supply units in a number of cities. In essence, the Chinese cartels provide the chemicals and machine tools and equipment needed to industrialise the production of synthetic drugs.

Indicted by the US Treasury Department for fentanyl trafficking, the Zeng cartel and its storefront, Global United Biotechnology, and a number of other cover companies which purport to deal in veterinary equipment, computers and retail, also have big operations in Mexico. Chinese money traders and businesses also increasingly launder money for Mexican cartels.

Part of this is handled through Chinese informal money transfer systems that, through mirror transactions in Mexico, China and the US, cleanse the money of Mexican traffickers while enabling Chinese businesses and citizens to evade capital controls in China.

The problem with great Netflix shows like Narcos is that the story ends when Pablo Escobar is killed. In real life that hasn’t happened. The big old major cartels have fragmented, which has led to increasingly adaptable, more agile and competitively violent criminal organisations coming up. Instead of just one big gang, you have the cartel Jalisco Nueva Generation, a whole bunch of others which are growing and consolidating power.

To further their competition with each other for control of drug plazas, those plazas being basically supermarkets which control the growth and distribution and logistical operations of the drug cartels, they’re actually vying for political power, intimidating local leaders, intimidating politicians, bribing police, bribing figures in the military — all to make sure that drug business can proceed uninterrupted.

Secondly, and not coincidentally, this cartel fragmentation process has created the circumstances for the geographical expansion of the drug gangs, because they need more and more territory to set up more and more drug plazas which can compete with each other. Territorial control of drug plazas is essential for the two primary goals of cartels — selling and trafficking drugs.

Third, cartels are diversifying and increasing in their criminal density, which means ordinary Mexican people are more and more exposed to violence and gang activity at greater levels than ever before. Mexican cartels expand, seek greater profit, and also turn in that process to activities like extortion, kidnapping, money laundering, fuel theft, and in recent years, most important of all, to the control of the lucrative business of trafficking immigrants across the border into the USs.

As you’ll doubtless have read, Mexico is the last most important staging post for tens of thousands of immigrants seeking from all over the world to enter the US. They stay in Mexican cities, and traffickers basically control their movement across the border in return for very hefty sums of money.

To be successful, a cartel must be brutal. There are videos around which show you just how savage the reality is. The one I’m going to tell you about is pretty typical. Masked men in combat fatigues use their knives to cut away their victim’s testicles as he hangs from his feet from the ceiling. Then one of the executioners peels the skin back from the man’s face and head. His head is then sawn off, followed by each of his limbs.

As the screams die out, pop music playing in the background breaks through, and you can see people standing around laughing as the slaughter proceeds, some taking pictures of the scene on their cell phones.

The seven-minute video unfolds with language precision and its maker understood something important. Terror is a medium. It can be not just to achieve a specific end but to intimidate entire communities and peoples. The world’s become familiar with this kind of aesthetic which flowered in the Islamic State’s execution videos. But the slaughter in that video is, if anything, worse.

The violence in Mexico has even spawned a new subculture and religion. Scholars Robert Bunker and John Sullivan have written about the trappings of Naco culture, which has a kind of parodic version of the Virgin Mary, Santa Muerte, the Goddess of Death, and worshippers turning to these Naco cults in a desperate effort to negotiate their way through this crazed landscape of terror.

Will Mexico be able to pull things back? Possibly. But as it does, it’s worth considering all the lessons India should be learning from this story. The country’s anaemic police forces, underfunded and under researched, desperately need to be able to act more coherently against the possession of illegal arms. The dangers of gun culture need to be talked about much, much more.

And the need for more police focus on organised crime should be addressed. Leaders of political parties and communities must have conversations about the consequences the growing pool of young disenfranchised people on our street collars and village squares could have. The nightmare in the other world could be our living reality one day if we don’t start looking at it and thinking about its lessons.

I’m Praveen Swami, and I’m a contributing editor to The Print. Thank you for watching this episode of ThePrint Explorer.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Collapse of 2 ‘Urban Naxal’ cases shows panic & police overreach are worse than Maoist insurgency