Bichhiya (Unnao): Rita Devi sits on an unfinished cement staircase landing, making big fat rotis and jackfruit curry on her clay chulha. It’s still 7am but she is done with half her chores. Wearing a glittery black saree, sindoor and kajal, her face glows. Life has been benevolent lately, partly because of the various government schemes that make things less tough for her and her family.

Her husband, Ramu Nayi, takes out his black Hero Splendor, a second-hand gift from his in-laws, and starts loading four big saddle bags, two on either side of the motorcycle. He is a ferrywala who goes from village to village, selling cosmetics and artificial jewellery. Thanks to his thriving business, Rita has all the make-up she ever wanted. Red lipstick, talcum powder, latest bindis and hair clips — Nayi gets it all. And she feels like a heroine.

Rita and Ramu’s life is on an upward trajectory. Aided by Ramu’s dedication to his family and his awareness of various government schemes that have helped him put a roof over his head, a gas cylinder for his stove, regular ration in his kitchen and some disposable money in his pocket. A battery of Modi’s rural welfare schemes launched over the last decade — PM Awas Yojana (rural), PM Kisan-Samman Nidhi, PM Ujjwala Yojana, Aayushmaan Bharat, Swachh Bharat Mission, and free 5kg ration per person of a household — is tipping scales in his favour.

According to the United Nations, 270 million people were lifted out of multidimensional poverty between 2005-06 and 2015-16. That decade of upliftment out of poverty, helmed by Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, made way for a decade of aspiration for India’s rural population coupled with a promise of achche din. Rural household expenditure more than doubled between 2011-12 and 2022-23. The trajectory of Rita, Ramu and others offers a glimpse into how rural lives have changed over the past decade, and what voter sentimentality is going to be as they line up to press the EVM button this General Election.

Ramu, a Class IX dropout, had to hustle to get access to the various schemes and benefits. He was the first one among his family to get a free gas cylinder, the first to receive a government monetary support of Rs 6,000 per year under PM Kisan Samman Nidhi, first Ayushman card, as well as a toilet.

“I meet so many people, and have established a good relationship with them. I am aware of things and keep enquiring on how to get access to benefits. I pass on this information to other members of my family, but they don’t hustle the way I do. I am also able to do so much because I have a bike,” he says.

Between 2014 and ’24, over 44 lakh houses have been constructed in Uttar Pradesh under PM Awas Yojana (Gramin). More than a lakh were built under the Indira Awas Yojana, which began to lose steam after 2016. There are 1.86 crore beneficiaries of the Kisan Samman Nidhi Scheme and 4.8 crore Ayushmaan Bharat cards have been created in Uttar Pradesh — highest in the country.

Agricultural economist and former agriculture secretary Siraj Hussain concurs that NDA’s welfare schemes have “surely helped the poor” but leaves a caveat: “the expenses on health, education and transport are rising. And incomes have not been rising for a majority of the population.”

Ramu emphatically admits his life was much more difficult before 2014, and credits the current dispensation’s policies for showing him what better days look like. “Ache dinn aa gaye hain (better days are here),” he beams.

Due to ground-level corruption, not every family has smiling faces in Bichhiya block of Unnao district. Even in the era of Direct Benefit Transfers, village headmen continue to play a crucial role in distribution of scheme benefits, often exploiting lower levels of literacy and awareness.

Another ferrywala, riding a bicycle, crosses Ramu’s path at a nearby village. Standing a few meters apart, both look for customers. The man on the cycle looks at Ramu longingly, as if he wants to be him. The Modi government, or any preceding government, hasn’t been able to infuse progress in ferrywala Balram’s life.

I meet so many people, and have established a good relationship with them. I am aware of things and keep enquiring on how to get access to benefits. I pass on this information to other members of my family, but they don’t hustle the way I do. I am also able to do so much because I have a bike

— Ramu of village Maita in Unnao

Also read: Portable MRI, water from air—Indian deep tech startups thriving with incubators, govt funding

The not so lucky one

Balram used to walk from village to village, often sleeping on an empty stomach. The cycle is a newly acquired ‘luxury’. He found it junked and got it fixed to ferry on. And with crooked feet, destiny has been cruel. He fell from a tree when he was a child. That brought him permanent spinal injury. He is currently living in his brothers’ house, a single room built in 2001 under the Indira Awas Scheme. The brother works as a cobbler in Lucknow. Since Balram needs money to buy food, he often repairs bags in barter for food such as flour, vegetables, and on good days, pulses.

Whatever little she could acquire in her 35 years of existence, Suman, Balram’s wife, has contained in bags she picked from other people’s trash. It includes her ration card, job card, and some clothes for the winter.

Balram, goes door to door in neighbouring villages on his cycle and repairs zippers of bags, pants, jeans etc. His tools lie in a small black bag perched on the cycle’s carrier. But no matter how hard he paddles, or how many kilometres he cycles every day, hard work is simply not bearing any fruit. “Our ancestors used to repair steel buckets. Once plastic buckets became the norm, we had nothing to do, so we learnt how to repair bags, and now that’s what we do,” says Balram, 40 who has been working as a ferrywala for the last two decades.

Balram could easily pass off as a 60-year-old man. His tanned face is deep set with wrinkles and a sense of defeat prevailing in his eyes.

The only thing standing between Suman and Balram’s family of five and starvation is the free 5 kg ration per month provided by the Modi government.

On most days, the family survives on potato and roti made on the clay chulha. During monsoon, there’s no place to store the free grains. So, when it rains incessantly, Balram and Suman are forced to hunt mice, something they have been doing for generations. That’s the only dinner they are able to serve their family, which currently has a teenage daughter, and two sons.

Two of their elder daughters are now married, and Balram is under debt of Rs 1 lakh he had taken to meet the wedding expenses. The only decoration he could afford for their weddings was writing ‘shubh vivah’ in orange sindoor on the walls of his brother’s house.

The family identifies themselves as Tharu tribals and are members of the musahar community. They remember a time when instead of agricultural fields, there used to be dense jungles near their village Toura in Unnao, and they as children used to venture inside the woods to hunt jackals, rabbits, turtles and mice to eat.

Except ration, toilet and one-time Ujjwala cylinder, no other benefits have reached this family. They don’t have a PM Awas, or Ayushmaan Bharat Card. They claim they’re not receiving BPL subsidy either. “We only get Rs 1,200 once a year to buy school uniform for our children,” Balram says. As musahars, they find themselves at the pit bottom of the caste pyramid.

Musahars here have been restricted to one part of the Toura village — Gandhinagar — where drain overflows and flies and mosquitoes breed. Life isn’t slow or spent near open fields, the place looks like an over-populated urban slum, with thousands of people trapped in a congested area. It’s a colony of huts, like wild mushrooms, and from every tiny hut made of straw, 5-6 kids emerge without clothes on.

Going to Gandhinagar from the main village settlement meant receiving warnings and caution from the villagers — to not consume the food served there since they are “not normal”. Upper caste villagers exhibit apathy towards the likes of Balram, describing their huts as “bhawans”.

Balram had his own house, now its destroyed.

“A bull charged into my home and destroyed it,” he cries, pointing to a pile of dry grass with sacks and torn clothes peeping out of the pile.

He is illiterate, and doesn’t have a vehicle to hustle from govt office to govt office to avail various benefits. “There’s no improvement in my life. Because of the free ration, my family can at least eat twice a day now. Our caste has had to live like this for generations. The food is enough only for the first 10 days of the month,” he says.

Balram bats for the Mayawati government to come back to power. His wife used to get Rs 2,400 pension every three months, which proved to be of great help.

How lives change

Sipping tea and serving snacks, Rita recalls the time she used to feel jealous whenever she looked at other people’s pucca houses, and hoped to get her own. “I had told bhole baba (lord Shiva) that if I get a house, I’ll offer one-and-a-half kg laddu at the mandir.

Her prayers were answered by the government of India. But not without the struggle. Six months ago, they finally got approval to get a colony (house) under PM Awas Yojana (gramin). Under the scheme, families without a roof get Rs 1,20,000 sanctioned in two instalments, which they have to use to build a house.

“I was so happy to buy that prasad once our house was approved. I went around the village distributing sweets and telling everyone that our colony has been approved!”

Rita remembers the time snakes would wade into her hut, keeping the family awake all night. The family would play ludo to distract themselves. “We’d look with a torch if the snake slid away or not. But sometimes, especially in the rain, they just wouldn’t move!” she says. When it rained, Rita and Ramu would wrap their kids in plastic sheets “like sheep” and drench in the downpour.

Rita has decorated her dream house which boasts of two rooms, a hall and a bathroom. She fashioned danglers with paper cups and plastic straws that hang on doorways. With a fully functional kitchen, she has been able to buy herself some crockery and containers to keep namkeen and biscuits in.

An old sofa set, eaten into by mice but patched up together, and a small curved screen television set sit in the living room. Rita happily watches Doordarshan whenever she gets the chance, provided there’s electricity in the house. Her favourite show is Mann Sundar. “I can happily call guests and friends to visit the house now. I can clean up privately in the bathroom too.”

The television is not a hit among kids who stick to YouTube, which they’re able to access after Ramu– and his smartphone– return in the evening.

The house has also helped her build intimacy with her husband. “It is very comfortable now. Though, I don’t want to have any more kids,” she says, blushing.

The couple share three kids — 16-year-old Ajeet, 11-year-old Sujeet and 7-year-old Shivani.

Rita works for a Lucknow brand that sells chikan kurtas, sending them one to two kurtas every month, finished with threadwork. The gig yields her Rs 550 per piece.

The family lives in a secluded part of the Maita village, mostly populated with OBC and SC communities. There is no pucca road to reach their house. Most of the children here go to the neighbourhood school. Once they return in the evening, they take their cattle for grazing.

It is a slow life amid farms and trees. The village looks like a place from the 1900s, but with traces of modernity. The kuchha houses are slowly being replaced by the pucca. There’s a small Swachch Bharat Toilet in front of every house, built in 2018. Rustling leaves, buffalo cries and YouTube videos playing on mobile phones form the background noise.

“At least we don’t shit in the fields where we grow our food in,” Rita Devi remarks. The family has built a second toilet for themselves with their own money, the Swachh Bharat toilet is now left for Ramu’s mother and brothers.

Rita combs the hair of her mother-in-law and later of her seven-year-old daughter Shivani. She looks for lice, crushing the parasites between her nails. Kids from the neighbourhood are here to take Shivani along – it’s play time. Shivani doesn’t want pigtails. “That’s not fashion. I want my hair open!” She protests unsuccessfully.

By late afternoon, everyone gets ready to greet each other.

Adults sit in front of a tiny shop, the only one in their quiet, that sells chewing tobacco, and compulsively eat the masala colouring their teeth red. They don’t talk much, and blankly stare in the sky. An occasional beedi is lit and chai is served.

Also read: Muslims say law and order has improved in western UP. ‘But voting for BJP against our imaan’

The jobs they do

The youth of the Maita either do traditional caste jobs, like barbers, midwives, or are two-wheeler mechanics. Some also work as contract labourers in Unnao, Kanpur, or even Lucknow.

But almost all of them have rejected MGNREGA now. What began as an ambitious project launched by former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh during the UPA government to prevent villagers from slipping below poverty line is now ailing. Low wages and rabid corruption have dampened the earlier enthusiasm for the scheme. Ramu says the only time he took employment under the scheme recently was during Covid, when he had been sacked from his job at a neighbourhood leather factory.

“There is no MGNREGA work here, so how do we benefit?”

Chief Development Officer, Bicchiya, Prem Meena says since the block is located on the highway connecting Kanpur and Lucknow to Unnao, people have access to higher wages and have never had an urgent need to find work under MGNREGA. “People find lucrative job options easily, perhaps in all of Unnao the popularity of MGNREGA has been comparatively low,” he said.

Though Ramu didn’t work under MGNREGA, other villagers who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said the scheme is riddled with corruption, and the village headman exacts a 50 per cent fee from them, or their payments are delayed. This is a major reason why they have chosen to opt out of the scheme. “I worked under the scheme long ago to construct a road. But I was never paid for it, so I stopped finding employment under the scheme,” a man in his late 20s said. He currently works as a construction labour in Kanpur and travels from his village daily.

Chief Development Officer, Bicchiya, Prem Meena says since the block is located on the highway connecting Kanpur and Lucknow to Unnao, people have access to higher wages and have never had an urgent need to find work under MGNREGA.

At Rs 240, the daily wage under MGNREGA is also discouraging, especially when people are getting employment outside (the village) for up to Rs 300 a day. “Around 2010, a lot of leather factories started opening in the area. And to attract labourers, these factories started offering wages which were higher than what MGNREGA offered. With time, these wages increased, but MGNREGA remained stagnant, discouraging people from opting for the scheme,” an official from the labour department in Lucknow said, on the condition of anonymity.

Social activists who have worked in the area, like S.R. Darapuri, a retired police officer and a politician, say that it is common for village headmen to seize the job cards and bank details of job seekers, and return such documents to beneficiaries only after taking their own 50 per cent cut.

But MGNREGS is the only rural scheme offering guaranteed employment, and work.

Ramu says MGNREGA was a life-saver when the coronavirus pandemic hit and a lot of jobs were cut at leather factories. “That’s the last time I worked under the MGNREGA project. I got my money on time, and also worked on creating a small pond for the village. I don’t know how I would have provided for my family without it.”

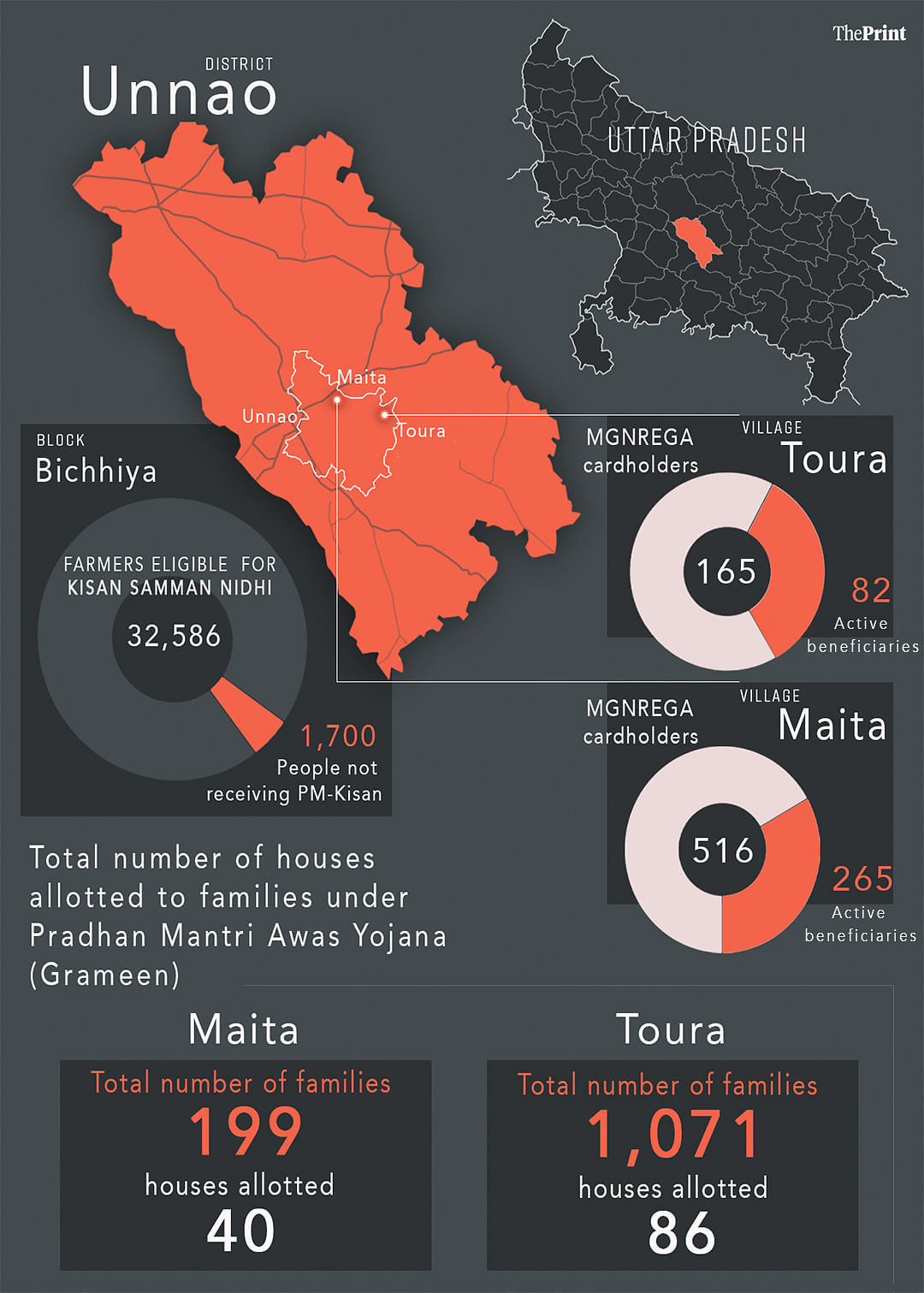

According to data provided by the Block Development Office, Bicchiya, Maita has only 162 MGNREGA cards, and of them only 82 are actively availing the scheme to find guaranteed employment. According to the 2011 census, there were 616 ‘workers’ in Maita. Even based on the 2011 figure, which must have changed by now, only 26 per cent of people in Maita were using MGNREGS.

The only thing villagers remember about the United Progressive Alliance era, which governed the country from 2004-14, were the one-room Indira Awas houses. They can’t remember the exact year when these houses were constructed but residents peg their age between 20 and 25 years. Because of poor construction and no repair work, those rooms today serve only as storage units.

Families have expanded since. When children get married, they build new huts near their parents’ houses. These second-generation Indians are the primary beneficiaries of the PM Awas Yojana. They’re now building bigger houses as they have a higher budget. But many are also investing and building better houses by taking informal loans. Much like Ramu.

Ramu’s mother, Munni Devi was also allotted an Indira Awas but doesn’t even keep her goats and buffaloes inside the room. “I would die if I lived inside. The roof will fall over my head,” the old woman says, lying on a charpoy outside her house. Indira Awas did help villagers access electricity and install a bulb and a fan.

Development has been uneven in the village. The colony where Lodhi OBCs live has seen no progress because the families didn’t vote for the current sarpanch. They don’t have Ayushmaan Bharat cards, awas, or even Swachch Bharat toilets. Bitti Devi is desperate for help – she doesn’t have an Ayushmaan Bharat card, and her husband is dying of liver and kidney failure. Illiterate and immobile because of lack of transport, Bitti is unable to knock on any doors for help. She doesn’t even have a ration card.

“I have approached sarpanch ji many times, but he doesn’t help,” she says. Bitti has taken loans from her neighbours and extended family to get treatment for her husband, and is surviving on ration that others donate to her. She roams around with medical reports of her husband in files that seem bigger than her build. The treatment cost is projected at Rs 5 lakh, and Bitti says she fears she won’t be able to arrange money.

Also read: It’s now clear. Modi wants a committed governmental, judicial machinery serving BJP vision

Casteism, corruption in way of vikas

This calmness of Maita village eludes Suman and her family, who have a dreary existence in Toura. The entire colony is dotted with kutcha houses, chulha smoke billowing from them. A foul smell envelopes the locality, and flies constantly buzz in the ears, biting away merrily on the skin. All huts have a small bowl holder made of rope dangling from the main piece of wood holding the huts together – this is to keep dogs and cats from raiding their food.

The villagers claim they live in the dark, cut out from the outside world, with no official visiting them. They allege upper caste leaders of the village don’t let any officials spend time in this basti. Piled up garbage is the view from most houses. They’re still victims of untouchability; dire warnings are given not to eat anything when visiting the area. “We don’t go to that part of the village. ‘Normal’ people don’t live there!” a villager told ThePrint.

CDO Meena refuses to believe caste-based discrimination could lead to problems in dissemination of schemes. “I have not observed caste being a hurdle in welfare dissemination,” he told ThePrint.

“I go to the pandits and tell them about my problems. But they always ask me to come back. No change comes to the village,” says Balram.

The PM Kisan disbursement — Rs 2,000 every four months — is used by families to fill gas cylinders, buy oil, or fulfil other necessities. But Balram and his family can’t benefit from the scheme as they are landless. PM Kisan is only applicable to small and marginal farmers who own cultivable land.

According to government data, the scheme has covered almost all of the eligible beneficiaries on record in the Bichhiya block. There are 32,586 farmers eligible for the scheme in records of Block Development Office, and only 1,700 are yet to avail benefit. None of the people in Balram’s basti are eligible since they don’t have any farmland in their name.

Women of the village claim to have begged many times before those in positions of power to look at their dire living conditions. “We want a colony!” (PM Awas) they roar. Their surroundings are full of filth, crying faces, desperation and hopelessness.

Only a handful of PM Awaas houses can be spotted in Gandhinagar.

“We’re discriminated against by the upper castes. They don’t let us near them, and don’t have any sympathy for us. Even when babus come, they don’t conduct extensive surveys in the village,” Balram alleges.

According to data from Block Development Office, 86 houses have been completed under PM Awas in Toura, while 40 have been completed in Maita.

The government’s welfare schemes and their delivery don’t factor in the caste discrimination on the ground that communities of Balram and Suman have faced for years.

Electricity reached their homes only in 2018 after metres were installed for free under the Saubhagya scheme. “Earlier, we would be restricted to our houses at nightfall. Electricity has allowed us some movement within the neighbourhood when it gets dark outside. Getting a fan also helps us in summers,” Suman says.

Balram and Suman have been unable to piggyback the progress train, or be blessed by Modi’s JAM trinity. Perennially living in survival mode, their conversations are limited to food, work and money. Balram is unable to buy his wife jalebis. “She tells me she wants to go to the mela but what will we do there? The other day I offered someone Rs 2 to buy jalebi, he started laughing at me, saying I needed at least Rs 10. I don’t like to see her disappointed like that,” he says.

Poor standards of living stunts the interpersonal relationship of the family. They don’t have outings, and can’t recall joyful evenings.

Vineeta, their daughter, says she hardly speaks to the family or has any fond memories of a fun day out. She’s a jaded 14-year-old. “I don’t dream about anything. I have accepted my fate,” she says. Vineeta just graduated from class IX and finished her free and compulsory education as part of the Right to Education. Her family doesn’t plan on sending her to school anymore.

But nine years of schooling has only made Vineeta graduate from using thumb impressions to signatures. To build up on her education, she seeks to learn a skill. The minimum eligibility to learn a skill under Modi government’s Skill India initiative is a Class X certificate. But free and compulsory education ends at class VIII.

“Unfortunately, the quality of education in Govt schools in many states is not at all satisfactory as Pratham reports show year after year. In several states, the society does not demand quality education in government schools. So, the enrollment in such states is declining” Hussain says.

The teenager says learning a skill will help her contribute to the family income. So her brothers don’t have to drop out of school and lead the same life that has so far sealed the fate of her family for generations. She wants to learn computers.

“We experience joy when we get to eat twice a day,” Balram says matter-of-factly. His daughter, Vineeta also casually remarked how Balram often hits his wife at night, at the slightest disagreement. Even though he says he doesn’t have the money to get a family photograph, he did go to a Mela once to get a photograph with his sons.

For Balram, the only thing he does for recreation is play cards with neighbours. Bridge (colloquially court-piece) is a super hit in the community. The women of the house don’t even have this luxury.

Also read: For ‘mahila’ voters in Bengal, making ends meet is priority & Mamata ‘didi’ their main benefactor

A stove and soft rotis

Ramu has saved enough to fill the gas cylinder. That means Rita will get to cook on the LPG stove and not chulha. “Exciting days are ahead!” She remarks over the phone while talking to a relative).

In his celebratory mood, Ramu bought a packet of macaroni at the insistence of his kids. Rita has learnt how to cook macaroni watching YouTube videos. Pepsi will be served alongside it.

But paneer still eludes them. “I know all urban people eat paneer ki sabzi. Even I want to try but it is so expensive!” Rita says.

Jio data revolution coupled with Ujjawala cylinders has helped the family get a taste of a global cuisine as macaroni.

“When I was a kid, the only ‘different’ food I ate was chaat at a local mela. I am happy that I am able to eat such things now,” Rita says, who also makes excellent chowmien.

The common roadblock with Ujjawala cylinders is the expensive refill. Even though the scheme has excellent reach, in most households the cylinder sits in the corner covered in cobwebs. The price of cylinders is part of conversations between women, who are upset that the government only gave them a cylinder to fill space in their tiny houses. They show their chulhas and scream. “See, I have to cook here! I don’t have gas in my cylinder. I have to send my daughter to the jungle to get wood!” cry’s Deepa Devi.

However, in households like Rita’s that have a little more disposable income, cylinders are filled up to thrice a year. It helps the family cook better, softer rotis and diversify their palette. Rotis made on chulha come out as fat rotlas that consume more flour and are difficult to gulp down. Stoves also maintain the quality of utensils, and reduce women’s labour in cleaning them later. In fact, the family feeds bajra and maize as part of ration to their cattle.

The Rs 2,000 Rita’s family receives — every four months — as part of the PM Kisan scheme also helps refill cylinders, buy oil and other essentials. The family also buys sachets of shampoo once a week to maintain hair hygiene.

Also read: Purvanchal’s migrant workers are desperate & poor. But they are determining India’s politics

Consumption or lack of it

The FMCG wave that started in the 90s and has grown ever since never reached these pockets of the country despite India seeing multiple prime ministers. Most villagers’ pattern of consumption is ancient. Balram and Suman eat the bajra and maize — part of the government schemes — and feed dry grass to a buffalo calf they’ve rented. Once it matures, the milk will be divided between their family, and the person who gave up the calf on rent.

Once a month, they buy Nirma detergent powder that they use for both washing and bathing purposes. And when they run out of Nirma, they use ash to clean themselves, as well as their clothes. Their kids frequent friends’ houses to eat food. “Sometimes my school friends invite me for meals. But that can happen only occasionally, I can’t eat there every day, after all,” Vineeta says.

The politics of food perpetuates discrimination against the family. In her school, recalls Vineeta, someone exchanged her tiffin with a girl from the General category. This led to the savarna girl allegedly charging at her and initiating a physical altercation. “She told me I’ve polluted her,” Vineeta adds, remembering that her school teacher buried the incident, and made her apologise to the girl.

Future, hopes and despair

Be it heat, cold, dust or pollution, Ramu’s bike loaded with cosmetics and artificial jewellry has rolled for years, going village to village. But now, he wants to board the next phase of upward mobility — an office job.

“I am unable to save with daily wages. If I get a salary, and see money in one go I’ll be able to save and pay off my loans,” says Ramu. He wants to work as an office boy, or a clerk. Rita looks at her husband lovingly and nods in agreement – a stable job would set their lives forever.

While Ramu works to explore his destiny, Balram has accepted his fate. “I will spend the rest of my life, yelling like sheep, urging people to come and get their bags repaired. Nothing will ever change,” he says bitterly.

As for Vineeta, she is waiting for the inevitable – marriage. Her parents want to marry her off as soon as she attains the legal age. And the teenager has made peace with this future. “I have some older friends who work as cloth sales executives in Lucknow. That must be a good job, in AC all day. I’d have liked doing that job,” she says. Her class VIII notebooks are full of notes jotted down in Hindi. These books will soon be discarded at the raddiwala for money.

There is time before Ramu, Vineeta and Balram’s lives would shift gears. Till then, the grind continues.

Ramu and Balram nod at the village intersection. Ramu kickstarts his bike and zooms off to the next village. Balram gives his cycle a little push and slowly moves ahead.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)

This is a brilliant balanced ground up story showing both hope and despair.. and more nuance at the ground than either vishwaguru or democracy in danger screeds from the 2 sides..

This is such stellar reporting. Reading articles like this renews my faith in Indian journalism

Extremely pitiful that such a condition still exists in our country and we call ourselves vishvaguru and want to spend money making statues.

Please share with me Balram’s contact details. I would like to offer him employment!

Thanks,

If people are happy with “ACCHE DIN” why does Modi have to play Muslim card again and again? Why does he have to put opposition party people in jail especially the AAP MLAs by misusing PMLA act in matters of corruption cases even when no proofs are found yet.