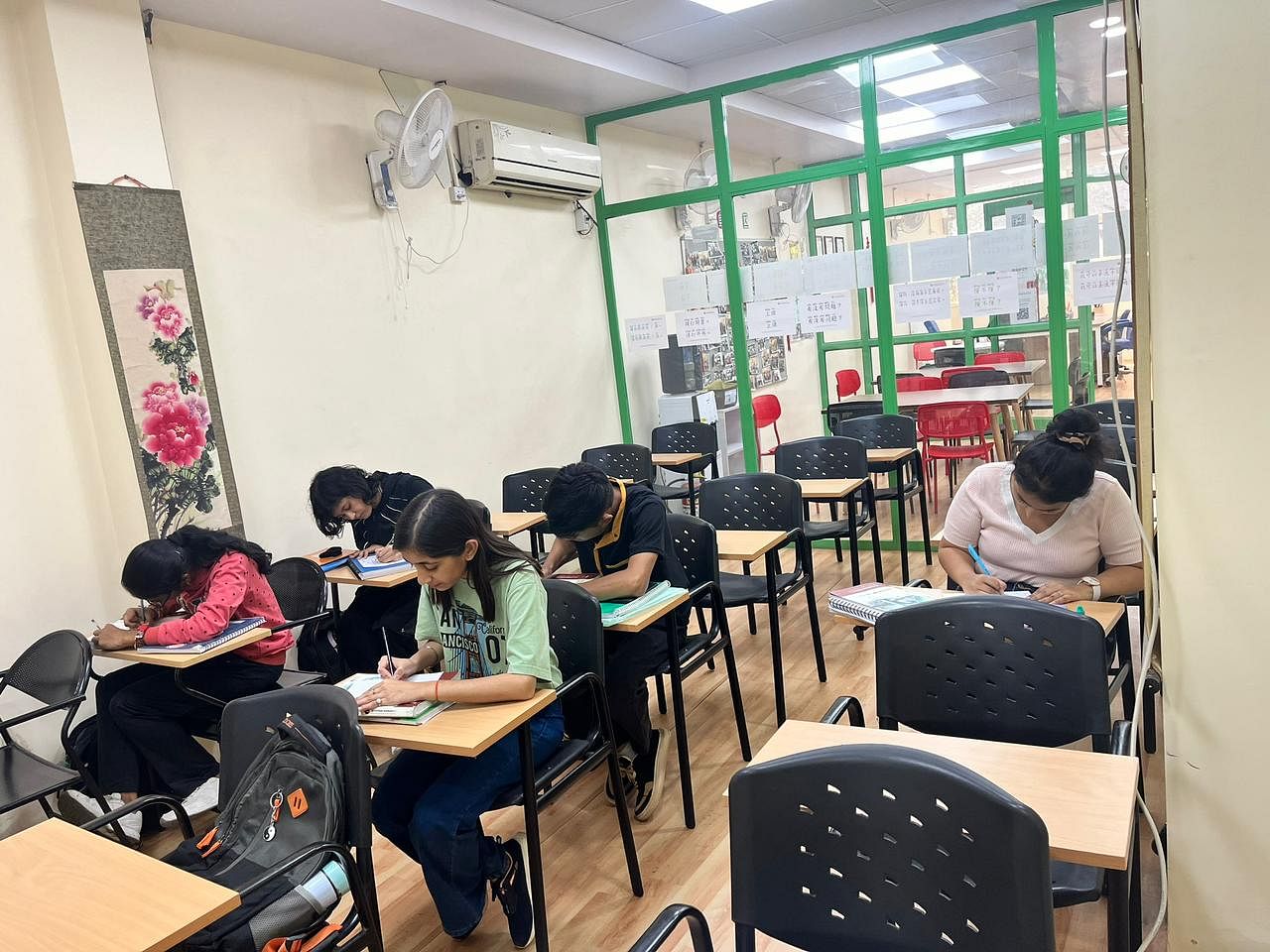

New Delhi: In a serene alley in Delhi’s bustling Karol Bagh, famous for civil services coaching centres and second-hand automobile and phone market, stands an odd institution. It’s akin to the elusive Room of Requirement in a Harry Potter movie, camouflaged from the casual observer but visible to those seeking it.

MeiYu Chinese Language Centre is a language institute that has been providing courses on Mandarin in the national capital since 2011.

It is one of the oldest private language centres teaching China’s official language to job seekers, think-tank researchers and scholars, government officials, and businesspeople. Over the past 12 years, it has taught Mandarin to nearly 2,000 Indians—most of whom enrolled in the last five years.

But Mandarin is no Korean when it comes to cultural fads.

Institutes such as the King Sejong Institute, the official South Korean government language school, received a staggering 9,696 admissions in its India branches in 2022 alone. The appeal of Mandarin is far behind that of Korean and Japanese, whose popularity is driven by their pop-culture effervescence.

The story of Mandarin in India is closely linked to China’s ascent to the global stage at the turn of the new millennium—its popularity intrinsically intertwined with geopolitical developments between the two adversarial neighbours. Translators and interpreters fluent in Mandarin emerged as the propellers of the India-China bilateral trade that has only boomed over the past two decades. But the Covid-19 pandemic and the 2020 Galwan Valley clash delivered a heavy blow to the travel and tourism industry. Many Chinese translators and learners lost jobs; students embraced other languages, classes ran empty, and many institutes shut down.

But now, Mandarin in India is seeing another great shift, propelled by the tension between the two countries.

Learners are seeking the language again, eyeing not tourism jobs, but opportunities in think-tanks, academia, big corporations, and government.

And they are not coming from elite bastons like Lutyens’ Delhi. Most of the students are from Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities in states like Bihar, say professors and Mandarin language teachers.

“Previously, those who wanted to make a career by being translators or tour guides..that sector has dried up,” says Jawaharlal Nehru University Professor (JNU) and sinologist BR Deepak.

The professor adds that many learners are also exploring higher studies or jobs in Chinese companies.

The winds of change blew into the country with Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit in 2014.

“Between 2011 and 2013, there weren’t a lot of Indian students. After Mr Xi came to India for the first time, interest started booming,” recalls Nancy Hsiao, co-founder and director of MeiYu. “Companies like Huawei and others came, and the chain started from there. They needed a workforce and someone to translate.”

Also read: After K-culture boom, Indian women loving Thai queer drama. ‘We can see 2 handsome…

Undercut by narrow scope

Sourav Ghorui, a 31-year-old investment banker, opened an online language portal called Bhasha Bhavana in September 2023 to continue his love for learning and teaching Mandarin. His 10-year journey mastering one of the most difficult languages in the world has provided him with opportunities to work for the government, as an ad-hoc faculty at Delhi University, as well as with the pharmaceutical company Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories.

When compared with other languages, the popularity of Mandarin in India is stymied by the lack of standardisation of courses, big and recognisable institutes and faculty. On Ghorui’s web portal, Mandarin has the least number of takers, with only about 50 inquiries in a month when compared with German, French, and other languages.

Ghorui points to the glaring lack of uniform parameters for teaching Mandarin — there are no standard books or course fee structures.

To add to this, Chinese investments on this side of the border have also significantly dwindled and India has become increasingly stringent in granting visas to Chinese nationals.

For the most part, MeiYu’s position as a well-known and established centre has made it immune to the troughs and crests of India-China relations. In India, foreign language institutes are part of a worldwide network of official bodies established by the home country, collaborating with local schools and universities to popularise the language. What Instituto Cervantes is to Spanish learners, Alliance Française is to French language enthusiasts, and Japan Foundation is to Japanese learners, Confucius Institutes (CIs) are to students of Chinese. But the CIs lack a broad overarching presence in India; the only two being the ones at Mumbai University and the Vellore Institute of Technology. These institutes, and other Chinese language centres, came under the scanner of the Ministry of Human Resource Development in 2020.

They sit obscurely within India’s foreign language story. Even academicians are hazy about the details. “There are one or two Confucius Institutes that are still running, but they don’t promote themselves too much, given the current atmosphere,” says a professor, requesting anonymity.

But Ghorui isn’t deterred by this.

“The number has decreased a bit. It could be because of fear or misunderstanding, but it’s not a considerable fall,” he says.

In a study that he undertook before opening his online learning portal, he noticed that there were more layoffs in Chinese companies in the past three years.

“People know they will get a job learning Chinese. The world is changing by the day. Many companies hire through LinkedIn. I’ve friends working abroad as Chinese language translators,” he says.

Moreover, he is certain that the market for Chinese language learning will receive a greater boost with “mobile phone companies opening more branches in India”, bringing in more jobs in the manufacturing and corporate sectors.

Also read: This immersive tourist centre in Seoul is every K-pop fan’s dream—music video sets, dance…

Bumpy crossroad

The reverberations of the rocky India-China relations are also felt in Delhi University. Applications for diploma courses in Mandarin at the university’s East Asian Department have witnessed a drop.

“In contrast to nearly 400 applications that were received against 49 seats for a Korean language course, the number of applicants for the Chinese course was quite less,” the professor says.

The merit list of selected students for a one-year intensive diploma in Chinese (CF-1) language reflected the drop — down to 32 students in 2023 from 44 last year. The disparity becomes even more pronounced when one looks at the number of students who enrolled into the advanced diploma course. A total of 34 students were selected in the academic year 2021-22, and that number plummeted by half to 17 for 2022-23.

Professor Rajiv Ranjan, who joined DU’s East Asian Department earlier this year after teaching at Shanghai University for nearly seven years, attributes the fall to the border dispute between the two countries as well as travel restrictions since Covid.

“There’s no direct flight yet between the two counties. It means minimum people-to-people interaction. The avenues for tourism and business are declining. People won’t opt to study the language under such circumstances,” he explains. He draws an interesting contrast: China started investing more in Indian studies after the 2017 Doklam stand-off, with at least 15 universities launching Hindi language courses till 2019 and opening many India-specific research centres.

Ranjan also points out an irony: While the Chinese language trod a rocky path in India, the interest in Chinese politics and culture and the number of China watchers only rose.

“In India, we see that the number of people writing opinion pieces on China has increased. However, the volume of serious Chinese language learners has fallen,” he adds.

At JNU, a luminous collection of Rabindranath Tagore’s works translated into Mandarin adorns the cabin of faculty member Usha Chandran. She, too, says that think-tanks analysing Chinese policy have mushroomed over the years but many of those working on China “can’t understand Chinese language”.

“It’s most logical to know Chinese to understand China. Without knowing the language, you are not looking at the primary source,” she says.

Having studied at JNU’s Centre of Chinese and South East Asian Studies in the ’90s, Chandran says that the West’s approach to geopolitics is different from Asia’s and it’s “always preferable” to understand China from the Chinese perspective as well as the Indian angle.

“The sense of righteousness and theoretical evolution of the West is completely different from Asia. Here, it carries a philosophical and religious history. Asian construct is different,” she explains.

In 2022, Chandran conducted a survey with the help of her student Raj Gupta to analyse the importance of Mandarin in Chinese studies. Out of the 300 student respondents, 68 per cent — all from various central universities — answered that they were looking to get a job by learning the language. Only 10 per cent were learning it because of their love for the language and higher research. The survey also revealed that around 53 per cent of respondents believed India lacked a proper understanding of Chinese politics and culture.

The reality of the job market

Chandran’s survey findings are in alignment with the realities of the job market for Chinese learners in India. For 27-year-old Shalini Kotnala, who is currently working at Tata Electronics, the scope for attractive employment was the driving factor for learning Mandarin. She assessed her prospects smartly before starting her course, gauging that there would be less competition given the difficulty level of learning the language.

“Compared to popular European languages like French or Spanish, the field of Mandarin speakers would be less crowded. There will always be a demand for Mandarin speakers and I wanted to be among those with the unique skill,” she says.

Kotnala took up a certificate course offered by St Stephen’s College in 2017 while simultaneously pursuing her undergraduate degree from Delhi University. She then completed her Masters from the East Asian Department with a specialisation in China.

When she tried for admission to language centres, “most of them declined”, citing the unavailability of Chinese language courses, lack of teachers, or delayed course dates. At last, she found a suitable online course at MeiYu’s in July 2021 and started working as a translator and interpreter in 2021.

In the past six years, Kotnala says she has observed a significant shift in interest in Mandarin learning, especially after the pandemic. She remembers that several of her fellow learners gave up when private language institutes shut down and the HSK exam, the Chinese government’s standardised language proficiency exam, was temporarily suspended.

“The suspension of the HSK test in India further discouraged potential students from exploring or pursuing a language,” Kotnala says, who, too, is aiming to crack the exam.

1990s to today

The clamour after Mandarin today comes after decades of gestating India-China relations. Deepak describes the 1990s as the “period of diplomatic equilibrium” between the two countries when the relationship was only just picking up. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi even visited China in December 1988.

It was also the period when Chinese companies were investing in India in huge numbers and all was relatively peaceful at the border. The 2000s marked the second phase of the equilibrium—while China hosted Summer Olympics in 2008, the Indian government decided on the expansion of central universities in 2009, which led to the establishment of departments focused on Chinese and China studies. Both countries were still “on the same footing in terms of development”, but things took a different turn only five years later. Border disputes started in 2014, and kept recurring in 2017, 2020, and more recently, in December 2022.

Despite the deterioration of India-China ties, the two-year slump in studying Mandarin during 2020 and 2021 is over.

Today, during a “period of disequilibrium”, Deepak says that “the mistrust” between Delhi and Beijing has led to the Indian government becoming the biggest employee of Chinese learners in the country.

“They are in great numbers in the home ministry, and to some extent, in the external affairs ministry and the defence sector,” he says, adding that there would be around 20 universities across the country where Chinese language classes are offered. The Indian establishment began to welcome people who knew the language, with the Army notifying jobs for Mandarin experts in 2022.

And Mandarin learners, dreaming of elite sarkari naukri aren’t from the likes of Lutyens’ Delhi. “Most of the students are from Bihar,” he says, adding that it could be because of the increasing popularity of Chinese in the state that saw a large influx of Chinese tourists to Bodh Gaya before 2020. Rajan and Chandran, too, note that most of the students were from Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities.

If Chinese corporations and research weren’t enough for job opportunities, the muscling up of Taiwanese investment in India looks promising to Mandarin learners. A Trade Promotion Council of India report released in August 2023 says that there are 250 Taiwanese companies in India and their investments have reached $4 billion.

Changing arc

Translators in the government, big corporations, think-tanks are being paid almost double.

“The translator level is getting higher compared to 2013. At the time, anyone with HSK level 3 could get a job. Now, the minimum requirement is level 4. We have our students in Amazon, and the minimum salary was previously Rs 60,000. Now it’s Rs 1 lakh,” says Hsiao.

The trend is also making learners want to study Chinese culture in detail. A minuscule section, mostly teenage girls, start learning the language due to their interest in Chinese TV shows.

Kotnala, too, joined MeiYu to learn the mannerisms of a native speaker, the people whom she needs to interact with as part of her job.

“The mannerisms and cultural nuances were missing in the classes at Delhi University. It’s not something that can be learned from textbooks. The native touch in a language can only come from native speakers teaching the language,” she says.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)