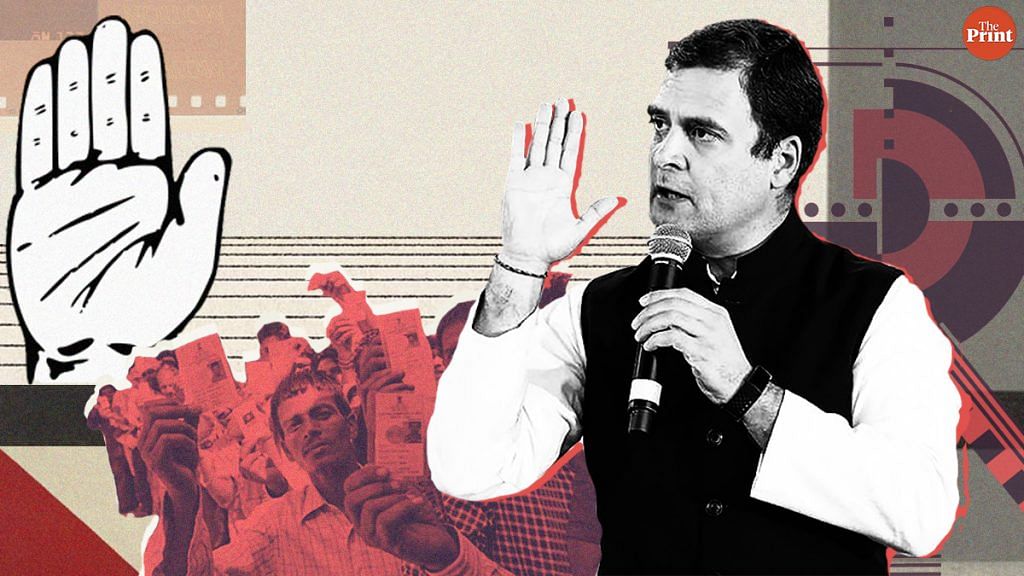

Congress president Rahul Gandhi Monday pledged to give Rs 72,000 a year to the country’s poorest families if the Congress is voted to power in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. Gandhi called his minimum income support scheme a “final assault on poverty”.

ThePrint asks: Rahul Gandhi’s Rs 72,000 income pledge: Are populist freebies the only way to win elections?

Doling out freebies without proper planning would lead to cut in productive investment & rise in borrowing costs

Economist, NIPFP

The Congress party has announced a minimum income guarantee of Rs 72,000 per annum to the poorest 20 per cent families in India. The party had announced freebies in the form of farm loan waivers prior to state elections as well. By design, minimum income guarantee is the least distortionary way of supporting the targeted poor, however, the timing of the announcement suggests that it is a populist measure designed to garner votes.

The implementation of such a measure is fraught with serious difficulties. First, the question of identifying the 20 per cent of the poorest is difficult and cumbersome. The criteria for identifying poor households would need to be set. Second, resource generation for the implementation of this scheme would need to be worked out. Perhaps the implementation would require rationalisation of subsidies, as some of these schemes benefit the not so poor. Rethinking would also be required on some of the existing tax concessions. All these are politically difficult questions. In the absence of these tough decisions, the practice of doling out freebies would lead to cut in productive investment and rise in borrowing costs – all of which would hurt the poor in the long run. These are legitimate questions in the minds of people and it would be desirable to have a detailed analysis of the pros and cons of such a move.

Not income support but reforms that help poor enter the workforce will be a successful economic model

Associate professor of Economics, JNU

There are primarily two major problems with this income support. First is a conceptual problem. The poor need to be given jobs to make them active participants in the workforce. Reforms are meant to help the poor earn a livelihood and include them in the labour force. That would be a successful economic model. All those who are willing to work and are in a position to work should be given the opportunity to live a life of dignity by earning their living.

The second problem is of implementation. How would one determine who are the 20 per cent poorest Indians? More importantly, how would they determine their family incomes? There are no mechanisms in place. Not only will this scheme run into bureaucratic hurdles, it doesn’t account for fluctuating incomes either. What happens when somebody with a secure job doesn’t have the job anymore? In professions like agriculture, farmers don’t have an income for many months until they harvest their crop and earn money.

The poor would any day prefer to earn a dignified living through work opportunities than live on these support plans.

Also read: Why vote buying doesn’t work in India

We must cheer the prospect of the election debate shifting to issues that matter to poor Indians

Professor, National Institute of Advanced Studies

The minimum income guarantee promised by Rahul Gandhi brings a much-needed shift in the political debate on the uncertainties facing the poor in a liberalised India.

Unlike the much-touted Universal Basic Income, a minimum income guarantee does not offer the same financial support to an ultra-rich as it does to the absolute poor. It also provides a link between support to the poor and their employment potential.

A strategy that offers employment opportunities to the poor would raise the income possibilities of their families to levels that are much closer to the guaranteed income, if not above it. The amount the government would have to pay to bring the income of all poor families up to the guaranteed level would then be much less.

Much would, of course, depend on how the poor are identified and how accurately the government estimates the distance between the poverty level and the minimum guaranteed income.

If the government makes the usual overestimation for political convenience, the cost of the scheme will go up to a level where it can hurt allocations for other critical areas like health, education and food security.

But despite these risks, there is reason to cheer the prospect of the election debate shifting, even momentarily, to issues that can make a significant difference to the lives of poor Indians.

Any income plan must be complemented by building access to basic services via public provisioning

Assistant Professor of Economics, OP Jindal Global University

Rahul Gandhi is offering Rs 72,000 per year as minimum income support to “poor” households – those with less than Rs 12,000 monthly income.

With limited information on the plan, I am sceptical about the scheme for following reasons.

First, in India, it is problematic to see poverty – in its absolute sense – as an explicit deprivation of income alone. It is rather a function of deprived capabilities (in access to basic social and economic services). Any basic income plan that, in its valuation, does not accommodate for basic costs to healthcare (currently with 65-70% as out-of-pocket expense), education, housing and others will quickly run into the problem of being too little for too few. Building access to basic services via public provisioning must be complemented with this.

Second, from a fiscal lens, any basic income plan can remain most feasible if, and only if, other means-based transfers (say, subsidies on food, fuel) are subsumed in it, or substituted with fiscal cost of affording such plan for the target group. From a revenue side too, in a highly regressive union tax system (with 65:35 ratio of indirect-direct tax base), maintaining fiscal discipline and paying for other subsidies are extremely onerous for the state.

Lastly, a strong assumption behind such plans presupposes that money allocated is actually spent for its intended purpose. This is rarely true though. A massive bureaucracy and paper-work create a problem of sludge, adding to high social and economic costs. There are, of course, gender implications (at an intra-household level) on how the basic income is actually spent by households that are entitled to receive free-cash without any conditions or monitoring mechanism. Hence, one needs more details and clarity.

From farm loan waivers to basic income support, every poll season witnesses a bidding war

Journalist, ThePrint

Ever since Indira Gandhi made populism popular in Indian politics, leaders across the spectrum have found it difficult not to succumb to the temptation. From farm loan waivers to basic income support, a bidding war starts in India during the poll season with scant regard for the long-term consequences of such actions.

Rahul Gandhi’s announcement of minimum income support is just one more addition to this list. As an abstract idea, a minimum income support sounds great. After all, who doesn’t want to remove poverty and ensure a more equitable society? But not all noble-sounding ideas can be translated into a tenable reality.

It’s generally politically difficult to implement something new at the cost of existing subsidies, many of which already suffer from leakages. And if this scheme is implemented in addition to the existing plans, it will only make the fiscal situation worse. The government is already finding it difficult to stay within its fiscal deficit target of 3.4 per cent. As a likely outcome, the government may transfer some of the financial resources presently allocated to other critical areas like infrastructure to this scheme. This will only hurt the poor more in the long run as most wealth redistribution policies generally do.

By Fatima Khan, journalist at ThePrint.