From Maharaja Ranjit Singh-era manuscripts to phulkaris and even Mughal coins, the Panjab Digital Library is making historical treasures digitally accessible.

Chandigarh: In a small dark room on the fourth floor of a nondescript building in Chandigarh, a young man laboriously pores over an early 20th-century work, the Mahankosh. He turns each page carefully, while a high-resolution camera overhead captures every word.

This is the Panjab Digital Library, which has taken up the task of painstakingly digitising one of the original copies of the Mahankosh, which was hand-edited by the legendary author Bhai Kahan Singh Nabha.

The Mahankosh is the first encyclopaedia of Sikh scriptures, put together on the lines of the Western concept of Lexis — the total bank of words and phrases of a particular language.

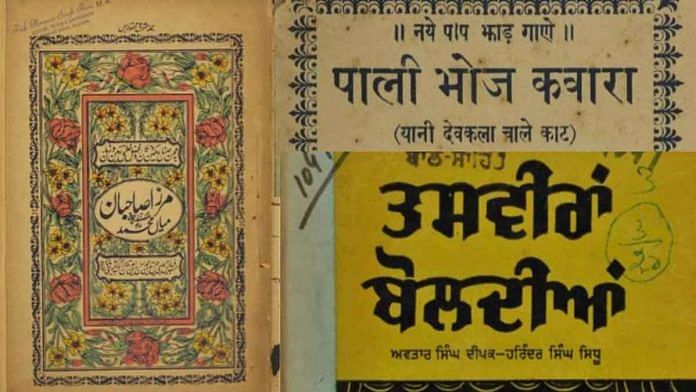

The Mahankosh continues to be a unique reference document of Sikh literature, and is one of thousands of Punjab’s rare historical treasures that the PDL has stored for posterity.

Almost 700 rare manuscripts from Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s Khalsa Darbar, written in the Persian script, have been digitised.

In another room, a steel locker stores hundreds of phulkaris (traditional embroidery) gathered from across Punjab and beyond, to chronicle every possible unique design.

Davinder Pal Singh, the founder and main driving force of the PDL, explained just why he took on these onerous tasks.

“The PDL emerged from a concern shared by a group of people for the fast-disappearing or already lost heritage of Punjab,” he said.

“Valuable material, rare literature, architecture, and signs of much-celebrated memories were completely destroyed by weather, ageing, or human aggression. But despite these losses, it was clear that there was still a lot left that was worth saving.”

Also read: Surprise: Nehru library also has the best collection of RSS’s Hedgewar, Savarkar papers

Rare maps, spy letters

Since 2003 — when the PDL began with a single computer and one employee — almost 19 million pages have been digitised. These include about 9,000 manuscripts, some of them dating back to the early 17th century. Another 41,000 books, almost 1.25 lakh photographs, over 6,500 rare and miniature paintings, and 5,000 maps have also been digitised.

“A map of ‘Hindostan’ dating to 1782 is probably the most detailed map of India made by the British. It’s one of a kind, and we were lucky to get it for digitisation,” Singh said.

The library is also the custodian of almost 5,000 qissa — the traditional form of storytelling in tiny booklets.

Then, there are over 65 rare ‘spy letters’ written in the early 18th century in the Marwari dialect, giving an account of the Punjabi-Mughal relations.

PDL has also made almost 10,000 artefacts digitally accessible, including about 5,000 coins of the Mughal and post-Mughal period, apart from nearly 1,000 wall murals.

“We are digitising almost two million pages every year, and for the next year, the target is to digitise four million pages,” Singh said.

The library’s main task is to digitise data for various government and private institutions. This data belongs to the institutions, and could even be part of a personal collection.

The PDL has, for instance, digitised data for the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), the Chief Khalsa Diwan Charitable Society, as well as the archive departments of the governments of Punjab and Himachal Pradesh.

“We capture the data in digital form and then make it available to the institution, which is then supposed to store and maintain it for posterity. But we also keep a backup of this data,” Singh explained.

“Whatever we have digitised is stored at six different places, and God forbid, even if there is an atomic war, all this material will survive.”

Innovation

In order to capture data which is available in the form of pages, lithographs, paintings, miniatures, cloth, coins etc., the PDL invents its own devices. “We had to create a whole machine to capture the designs of the phulkaris. For books of various sizes, another piece of specialised equipment was prepared,” Singh said.

In 2009, the PDL decided to make this data available for use by researchers. It became the first organisation in South Asia to launch an online digital library, showcasing manuscripts, books, newspapers, magazines and photographs for free public use.

“The idea was not just to preserve everything, but also to make it available for researchers and scholars to use and generate fresh insights into Punjab’s history and the life of its people. The digitisation of history holds great promise in research education and awareness, while saving precious time and money,” Singh said.

The PDL is now also generating awareness about the state’s rich heritage. It has developed and hosted more than 10 exhibitions using digital data.

“We curate the digital data and choose what we think is the most telling document of that time, and gather such items together for exhibitions,” Singh added.

“I believe that whatever we are doing here is part of a much larger global effort. This is for the second time in the history of the world that knowledge is migrating from one form to another — the first time was when writing was invented, and knowledge was transferred from the mind to paper.

“It is a revolution, and therein lies the significance of what we are doing.”

Also read: New Teen Murti museum on memories of ex-PMs doesn’t snuff out Nehru’s legacy by any means

Funding crunch

The funding for the PDL is largely through local donations. However, for projects that the PDL does for the government, it gets paid a nominal amount.

“Despite all the talk that we hear about preserving our culture, tradition, heritage, most of the governments are not very forthcoming in setting aside funds and actually doing something about it,” Singh said.

“A typical digitisation project, even on a small scale, requires a big budget by any conservative estimate. We are seeking to promote an entirely new culture of awareness, where the masses contribute to the safeguarding of old texts.”

Without any initial infrastructure, expertise or funds to support the project, the PDL has somehow not only survived, but excelled through sheer motivation and concern for the heritage.

“We have identified almost 80 million pages, for which we have partial permission to start digitising. But if we continue at the same speed that we do now, it will take us another 40 years. We need to expand, we need more space and to hire more staff, to be able to take up the entire workload,” he said.

This article has been corrected to reflect that the Mahankosh was edited by Bhai Kahan Singh Nabha in the 20th century.