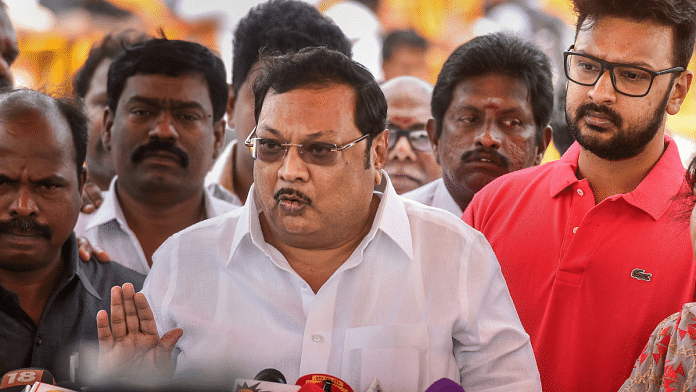

Chennai: The streets around M.K. Alagiri’s house in Madurai’s TVS Nagar are filled with posters of him. Some of them announce the weddings of couples who are his supporters, while others call him Anja Nenjan, meaning braveheart — a nickname given by his fans.

The area, lined with multiple bungalows, was a hub of political activity when Alagiri was still the powerful son of “Kalaignar” (artist), the late Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) chief M. Karunanidhi.

But now TVS Nagar is quiet. The only time it saw some buzz was in January when Udhayanidhi Stalin, Tamil Nadu’s minister for sports and youth welfare, visited his uncle.

The friendly interaction between the two raised some eyebrows, as Alagiri and M.K. Stalin, the DMK president and chief minister, had a bitter rivalry in the past. Alagiri, a staunch critic of Stalin within the party, was expelled from the DMK in 2014 for ‘speaking ill’ of him. In the years since, most of his former associates have joined Stalin’s camp.

The brothers made headlines again in July this year when they met at Karunanidhi’s Gopalapuram residence in Chennai on their mother Dayalu Ammal’s 90th birthday.

“I think Alagiri’s actions have been buried and he has reconciled himself to the status quo with Stalin. But from what people say, he may not return to full-time politics, and there is no talk of rehabilitation, that is, talk of him getting back into the party or gaining some position in the DMK,” said S. Annamalai, a political analyst.

In the years since his expulsion, Alagiri — once seen as the DMK’s strongman in southern Tamil Nadu — had hinted at various political moves. But none have materialised.

In 2019, when actor Rajinikanth said there was a political vacuum in the state, Alagiri reportedly said, “Rajini will fill the vacuum.”

There was speculation that Alagiri might even join Rajini’s party if he launched one, as they are said to be good friends.

Then in 2020, ahead of the 2021 state assembly polls, Alagiri reportedly said that he was in discussion with his supporters to decide whether to float a new party or back an existing one.

“He might have had some chances of floating a party 10 years ago, and he himself had sort of indicated that possibility, but now I don’t see that happening,” said Sumanth C. Raman, another political analyst.

There were even rumours in the political circles that Alagiri might support the Bharatiya Janata Party(BJP), which he denied later to reporters in Madurai.

But when one interacts with his close aides, they say that he never had any interest in politics in the first place.

“However, when he got into politics, he was loyal to the party and worked towards ensuring the party’s success,” said K. Esakkimuthu, a close friend of Alagiri for 43 years who was expelled from the DMK alongside him.

Now, after being expelled from the party, Alagiri has again has lost interest in politics, Esakkimuthu said, adding, “Alagiri is now busy looking after his farms in Madurai.”

ThePrint reached several senior DMK leaders and party spokespersons over the telephone, but all refused to comment on Alagiri.

Also Read: ‘Confronting Sanatana Dharma an old tradition’ — why Udhayanidhi remark hasn’t shocked Tamil Nadu

Madurai — Alagiri’s bastion

Alagiri is Karunanidhi’s eldest son by his second wife, Dayalu Ammal. His reputation is that of an impulsive strongman with a short temper.

But for his aides, he is a “man with a golden heart” who would do anything for those close to him.

“He came rushing to see me at the hospital when he heard I had a minor accident last month. I told him it was not necessary, but he still came,” recalled Esakkimuthu.

“The first question he asks anyone who comes to meet him is if they have had anything to eat or drink. He has a very helpful nature,” he added.

His associates also say that instead of calling him short-tempered, people who know him understand that he has a “childlike heart”. “He gets angry quickly, but he also forgives and forgets as fast,” said a former loyalist of Alagiri from Madurai, who did not wish to be named.

It was in the 1980s that Alagiri moved to Madurai to manage Murasoli, the DMK mouthpiece. “He used to ride his Lambert scooter to and from the Murasoli office and his home. He often spent time in his video lending library,” said Annamalai.

In Madurai, Alagiri gradually built up a base and found staunch supporters for himself. According to Annamalai, “His close friends describe him as friendly, always caring about their well-being, and there were even people who then used to say that they would die for him.”

However, his rise did not sit well with many senior leaders, who feared a factional war in the region, added the analyst.

The two brothers — Alagiri and Stalin — were also said to be always at odds over who would be their father’s heir. While Karunanidhi had started grooming Stalin as the next in line, the elder son is said to have had differences with this choice.

In 2001, Alagiri was expelled from the party for the first time after he was accused of asking cadres to boycott a conference that was organised in Virudhunagar by Stalin, who was the then DMK youth wing secretary.

But the same year, he managed to show his strength in the Madurai Corporation Council polls. Seven of his followers won as Independent candidates in the elections to the 72-member council, and one of his supporters became deputy mayor.

In 2003, when former minister and senior DMK leader T. Kiruttinan was hacked to death following a factional fight, Alagiri and 12 others were accused in the case. Alagiri was reportedly arrested and lodged in Trichy Central prison. However, he and 12 others were acquitted in 2008 by a district and sessions court citing lack of reliable evidence.

Alagiri’s “notoriety”, political commentators said, increased over the years, and in 2007 his supporters had reportedly set fire to the Dinakaran newspaper office, owned by his cousin Kalanithi Maran, after a survey done by the paper projected Stalin as Karunanidhi’s successor.

“People around him tried to divide the state into north and south and tried making him the king of the South. This they could achieve only to a limited extent,” said Annamalai.

The analysts also said that Alagiri, who was far from Chennai — the political headquarters of the state — never had a political orientation, and was not a good speaker, or an orator like his father. “But was more of a brash man,” said Annamalai.

In 2009, Alagiri became infamous for the “Thirumangalam formula” , said political analyst Annamalai, referring to alleged vote-buying that is supposed to have helped the DMK secure victory in an assembly byelection in the Thirumangalam constituency that year.

But Esakkimuthu said, “Voters always have been used to getting something during the elections. Earlier, it was money for tea or snacks after polling, and now it is in a different format. Right from the time of the Congress’s rule in the state, voters have been given some form of assistance.”

“Alagiri would do anything to bring victory for the party,” he asserted.

The party rewarded him with his first official posting in the DMK as the south zone organising secretary, and soon afterwards, he contested his first Lok Sabha election from Madurai and won. Alagiri was also made a cabinet minister in the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government at the Centre between 2009 and 2013.

“In the history of the DMK, Alagiri was the first DMK leader to win the Madurai Lok Sabha polls. The DMK’s allies may have won, but never once was the DMK on its own able to win. That history was changed by Alagiri because of the groundwork he had done over the years in Madurai,” said Esakkimuthu.

Also Read: Ask Stalin questions, get info on govt work, register as party worker — DMK’s new one-stop app

Fading from political scene

Alagiri was expelled from the party in 2014 for openly challenging his brother Stalin and questioning his father.

Unlike in 2001, his fate was sealed this time.

After Karunanidhi’s death in 2018, Alagiri tried to make a comeback in the party and had even reportedly said that he was ready to accept Stalin as the leader of the DMK. But the then general secretary, K. Anbazhagan, decided to stick to Karunanidhi’s decision on Alagiri’s future.

Meanwhile, Stalin made sure that the party stood behind him as its chief.

Unlike Stalin’s son Udhayanidhi, Alagiri’s children — son Dayanidhi Azhagiri, a Tamil movie producer and distributor, and daughters Kayalvizhi and Anjugaselvi — have all stayed away from politics for the most part.

Between 2008 and 2011, Kayalvizhi was active in DMK, and in 2011 many saw her as a rival to Kanimozhi, said political analyst Priyan Srinivasan. But she left the political scene soon afterwards.

After the DMK’s victory in the 2021 assembly elections, Alagiri reportedly congratulated Stalin and even said that he was “proud” that he had become chief minister.

Since 2021, Esakkimuthu said, the former Union minister has settled into taking care of his farms. Most of his former close aides have joined Stalin’s camp and been taken back into the DMK.

“There were many who used Alagiri’s name to make money, but now all of them have switched sides,” said Esakkimuthu.

According to his aides, Alagiri now avoids attending even functions of political workers close to him, and is seen at public events very rarely. He does not want to be in politics anymore, said another close aide.

But for his old loyalists, the doors to his house remain open. “A few of us go to meet him often. We sit and talk for hours together,” said Esakkimuthu.

But will Alagiri return to politics? Political analysts are of the opinion that a 10-year break in politics is a long time to make a comeback unless Stalin wants him on board.

“He is already past the age of 70, and unless Stalin wishes him to have some role, it’s extremely unlikely for Alagiri to be able to achieve anything within the DMK, because the party is completely and totally behind Stalin,” said Sumanth C. Raman.

(Edited by Richa Mishra)