In so many years of making a living covering troubled zones there were at least two occasions I was convinced things would never return to normal. On both, I’ve been proven so wrong.

The first was early one morning in the bloody fortnight of February in 1983 Assam. More than 3,000 bodies lay around a village called Nellie. Freshly slaughtered, bleeding, many walking wounded with blank faces, dry, blank eyes, some even holding the entrails spilling out of stab wounds. How could Assam ever come back to normal?

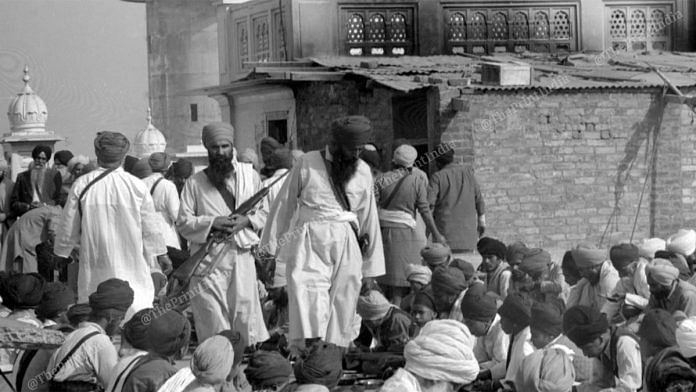

Or Punjab, 1984. On the night the army swamped it and imposed martial law of sorts for a week, tanks boomed at the Akal Takht and then the assassination of Mrs Gandhi and the massacres of Sikhs. The Rajiv-Longowal accord was a short-lived hope that died with the assassination of the ever-so-reluctant Sikh moderate. Then the return of terrorism, the killings, kidnappings, the kangaroo courts. Tax collections by the terrorists, the humiliation of having to show your press credentials to militants manning “checkpoints” in some parts of the border districts that some in the media had begun to call “liberated” territories. How could anyone ever turn the clock back in Punjab? How could Hindus and Sikhs ever go back to being nails and flesh — of the same finger?

Drive through Punjab now and see how. That dark phase is not even a blip on anybody’s mind. The highways are better than before, with water parks and more, the traffic faster, the paddies are lush and the mood robust and virile. At the installation ceremony of Amritsar’s Rotary Club, the city’s most successful and prosperous Sikhs and Hindus give each other plaques and trophies in a manner so Rotarian and talk of donating money to “beautify” the cremation grounds both communities obviously share. Just a decade ago, even in the district courts of the supposedly more cosmopolitan Chandigarh, you found Hindu and Sikh lawyers sitting at different tables, looking at each other with sullen suspicion. The divide had seemed so total. So irreversible.

The late Mehra saab, or “Tiny” Mehra as he was nicknamed with typically misplaced Amritsari understatement since he packed at least 130 kilos in his six-foot-plus frame, owned The Ritz. The hotel was the favourite of the media’s soldiers of fortune, and often after counting the day’s dead we sat with him for òf40ógup-shup and òf40óchai sessions. One evening, he startled me, the only guest in his hotel during the week of Operation Bluestar, by announcing that he was borrowing money from Grindlays and adding another wing to his hotel.

“But you must be out of your mind, uncle,” I said. “Which tourist will ever come back to Amritsar now?”

“You will never understand,” he said, “People are very tough. They will learn to live with terrorism as you learn to live with diabetes. A little medication, exercise, a few restrictions and you could go on for ever.”

Then, it sounded like madness. Today, even though he is not around to enjoy his own vindication, even that so-called “diabetes” has vanished without a trace. It feels, instead, like a terminal disease after cure and remission. Both wings of The Ritz, now part of a Mumbai hotel chain, are booming. So are many other hotels, including brand new ones with specialty restaurants, where you have to book a table in advance. The Domino’s and `Burger King’ outlets are packed, brushing aside the swadeshi challenge of some old òf40óchana-bhatura wallas that now hawk “newdels and bargars” or “South Indian and Chinese snakes”.

The sunrise businesses are computer training centres, slimming clinics and beauty parlours. At Rayya, just short of Amritsar on the Grand Trunk Road, the police station does not even have a sentry at its open gates. In the past it was a fortress with machine gun nests and bunkers. Even the old humour is back. Look for the tractors with Mercedes 560 SEL or BMW plates, besides, indeed, any number sporting the Maruti 800 logo. The fields have even fewer Sikh workers than before — they now make more money in jobs, trucking or other businesses with many more migrants from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, the òf40óbhaiyyas, doing the job at the best agricultural wages anywhere in the third world. Again, in so many years of covering insurgencies, I have seen only two that disappeared so suddenly. With such finality. The other one was led by Sri Lanka’s ultra-Sinhala Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna that died with its leadership, put away in cold blood by Jayawardene’s vigilantes. Can there be a common reason why these twoinsurgencies have ended with such finality?

Also read: In wrong place at wrong time: Forgotten story of Operation Blue Star’s ‘Jodhpur detainees’

In the Amritsar of Bhindranwale, the killer squads, Punjab Police’s “cats”, Bluestar and worse, there was one man with a big heart, a voice of sanity and with doors always open to harried, hungry and thirsty hacks. Dilbir Singh ran a flourishing woollens business, managed the affairs of scores of Khalsa schools and colleges and found time for his favourite Rotary Club. Since he lived just across the street from The Ritz, you could reach his house even during Bluestar’s shoot-at-sight curfew. He was an optimist too, but in a manner less blase than Tiny Mehra’s. “This is bound to end one day,” he would say. “The Sikhs themselves will realise an eight-district Khalistan will be too small for them to even park all their trucks. We want all of India, Bombay, Calcutta, Delhi.” Dilbir Singh and his family took their chances. He never accepted police protection, never flinched from speaking his mind though in a voice so sober you sometimes wondered if he belonged to that city in those shrill times. But he had abelief. People, like the Punjabis, and the Sikhs in particular, who have a stake in their future, do not put up with nonsense for ever.

That is possibly the common reason why the JVP and the Punjab insurgencies ended with such finality. Peoples, ethnic and linguistic groups that have tasted prosperity and thereby a stake in their future, have a strong immune system of sorts that fights back from within. The Sinhalas and the Sikhs are the two richest communities anywhere in the subcontinent and have the highest social indicators. Contrarily, some trouble in Assam still festers. There are still too many people far too poor to have a stake in stability. But this is also exactly why all of Mumbai turned up for work the morning after the serial blasts. Upward mobility brings its own unstoppable momentum. Punjab’s return to normalcy is pretty good evidence of that.

But there is also a serious difference. Mumbai runs on business and enterprise. Punjab survives on agriculture which is no longer quite the same driving force as modern enterprise. Punjab’s is the story of a state that rode the crest of the green revolution but missed the industrial revolution altogether. The greatest tragedy of the post-insurgency years is that nobody has addressed that issue and the result is stagnation, joblessness, and bankruptcy of a government that still runs in the old, agricultural paradigm, giving out doles, even mortgaging its state roadways, bus stations and buildings to pay its employees’ salaries.

In the past eight years, Punjab’s GDP growth rate has been lower than the all-India average. According to data compiled by the Centre for Monitoring of Indian Economy (CMIE), Punjab grew between 1991 and 1996 at 4.6 per cent against the national average of 5.6. Today the gap is even larger. In terms of infrastructure growth, Punjab’s story has been disastrous. It’s been growing at 2.1 per cent, against the national average of 2.6 and, believe it or not, Bihar’s 4.8. It may sound outrageous to compare Punjab unfavourably with Bihar on any developmental parameter but you can’t fight with the facts.

If there is one thing that hasn’t revived in post-insurgency Punjab it is industry and enterprise. The shells of dead, defunct factories and foundries along the highway are like the wrecks of Basu’s Bengal but growing inside them are the seeds of the revival of trouble. Agriculture does not produce enough to satiate the Punjabi, nor does it keep him occupied around the year. The government has no jobs and industry is decaying. We may not see the return of old terrorism, but how long will it be before the old anger and frustration return, maybe as some kind of a viral variant of the old disease?

Postscript: Some things have changed for the worse. The dhabas, for example. My old favourite, the Zimindara Dhaba, 10 km short of Ludhiana, has lost all character to gentrification. Instead of what used to be a limited menu of the world’s finest black daal, saag and fresh rotis, it now sells shahi paneer and malai kofta, much like the slobbery rubbish you eat at Delhi’s wedding hall buffets. Gone are most of the charpoys, fresh butter and the very subtle aroma of freshly churned buttermilk. Mercifully, it serves no Chinese and South Indian snakes, newdels or bargars. At least not yet.

Also read: Why Akalis & AAP are reigniting 1984 anti-Sikh riots issue in Punjab