Personally, Atal Bihari Vajpayee has admirers across our political spectrum. But even if you are not an admirer, you’d understand his agony. In his first public appearance after RSS chief K.S. Sudarshan’s attack on him in a Walk the Talk interview with me (the text of which will appear in this paper, The Indian Express, this Sunday) he was almost close to tears as he said he feared calumny more than death. He did not name anybody, but he was obviously referring to the charges Sudarshan made, against him, his closest advisor and family.

In the heat and dust of these charges, another significant thing that Sudarshan said must not be forgotten. When asked if by “failing to deliver” – as he thinks he did – Vajpayee denied himself his rightful place in history, Sudarshan said, what can I say, I am a contemporary (samkaleen), it will be for historians to judge. And then he went on to suggest that dispassionate history is generally written 30 years later.

But as a samkaleen, there was no doubt that he did not think Vajpayee deserved that place. Yes, he did a few good things, nuclear tests, shepherding of the national interest in a hostile world, but not very much else. There is no credit for economic reforms, in spite of the opposition from the RSS and its affiliates, usually manipulated by corporate lobbyists of one persuasion or the other. There is no mention of the peace process he initiated, of the national highway project, of raising India’s economic growth benchmark to a level twice as high, ironically, as the old Hindu rate of growth. His big “failure” is not making any progress on the Ram temple and not being able to take his ideological cousins along.

Look at it this way. In this worldview, what Vajpayee achieved for India, or his performance in terms of governance, is secondary to what he did not do for the ideology. It is not so important that future generations would remember and thank him for establishing so many new benchmarks in economic reform, for breaking our fear of thinking big on infrastructure, for leading India quite effectively in a very complex foreign policy environment, which was laden with opportunities as it was fraught with threats. The truth is, when India’s history is written 30 years hence, and hopefully we will be so evolved by then as to have genuine historians write it instead of members of either a Murli Manohar Joshi or an Arjun Singh cabal, Vajpayee’s six years will be recorded in pretty good light. Maybe his picture will not adorn the offices of the RSS but future generations of Indians, by and large, will see him in much better light.

Vajpayee’s record, however, was not unblemished. Non-partisan historians will, for example, have an issue with him on his handling of Gujarat and Modi. I am sure some of them would also say that Vajpayee denied himself a much greater place in history by failing to fire Modi when he could have done so, of how those hours of indecision and lack of conviction during his party conclave in Goa cost him true greatness. Chances are, those historians will also note that he was under extreme pressure by the same RSS which saw in Modi a truer reflection of their own philosophical and political beliefs. This will, however, be no alibi for Vajpayee. When history of great men is written, authors do not embellish their failures with footnotes explaining how someone else was to blame.

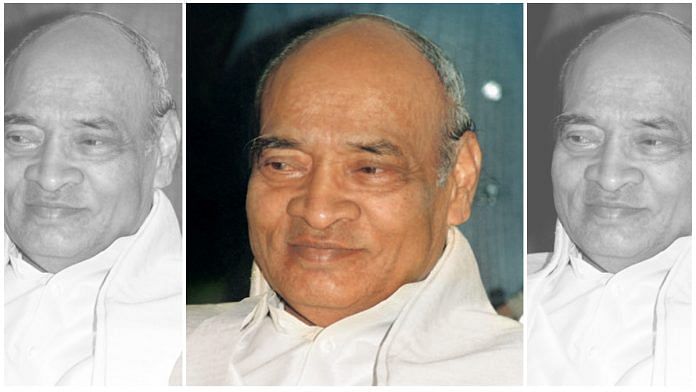

Also read: Why Congress has now woken up to own PV Narasimha Rao’s legacy

Historians are clinical, cruel people. But they are less likely to be as unfair as contemporaries. And resentment of the contemporary is not confined to the guardians of ideology. The Sangh Parivar’s anger with Vajpayee is not so different from the way the Congress has tried to forget the Narasimha Rao phase, as if it was not their government that he led. He was ignored in his post-power years, most party leaders were afraid even to be seen with him, he was denied honour in death. A Congress government is in power now. But if there is a proposal to name a road, an airport, a train after him, or to issue a postage stamp in his memory, we know nothing about it. The man who helped him change the course of India’s history in the midst of a terrible economic crisis, Manmohan Singh, is now the prime minister. But has anybody even made a move to propose his name for a national award? Even Rao’s own Congressmen do not consider him worthy of any of this, not even a thank you note for keeping them in power for five good years.

The bitter truth is, the Congress would want to deny Rao his rightful place in history exactly for the same reason that the Sangh Parivar would prevent Vajpayee from claiming his. If one is to be repudiated for defying his political ideology, the other must be made to pay for not kowtowing to his party’s first family. In effect, it means the same thing. The Family is to the Congress what Hindutva is to the RSS. It is the abiding legacy that you defy at your own risk. Both the Congress devotion to the idea of the first family and the Sangh Parivar’s to its ideology are camels in their respective tents even today. In denying these two leaders what should be their due, both ultimately undermine themselves. The BJP is already paying gravely – and paid in May 2004 – for chipping away at the Vajpayee brand. The Congress, by pretending that its history in power ended in 1989 and resumed in 2004, with the Rao years a forgettable blur, does damage to itself.

What does this mean for others who might rise to the top job? What would it mean, for example, for Manmohan Singh, and the mark he makes on our history? Unlike Rao, he has been chosen by Sonia Gandhi and has her support. Unlike Vajpayee, he is not at odds with his own party’s ideology. But he does challenge his party’s dominant culture in that he is neither a sycophant nor a lightweight. He has ideas of his own, his own way of getting things done, and has begun to notch successes of his own now, from economics to foreign policy. He has done enough already for whispers to begin within his own flock, of how “Mrs Gandhi is unhappy” with him, of how his government is soft on her political enemies and so on.

But he has a unique advantage. Unlike Rao, he is a choice of the family and will never be accused of undermining it, since he has no ambitions beyond this term. Unlike Vajpayee, he is not expected to pay any special dues to his party or ideology. He was not a candidate for the job, and his party needs him more to run this coalition than he needs this job. He, in effect, has the remarkable opportunity of rewriting history in a manner the camel in the tent cannot. The experience of Vajpayee and Rao will be good lessons to keep in mind as he goes along.

Also read: Between Vajpayee and Modi era, RSS has learnt many political lessons