While the entire nation watches in disgust the deal-making and horse- trading that mark the current turn in our politics, let us not overlook the rather profound questions that got us here. For, while today a life-saving vote may be traded in exchange for things of such lasting value for future generations as the renaming of an airport, a ministership for six months, a more winnable seat for the next election, or straight-forward cash, let it not confuse you into believing that this entire crisis is about either surviving in power for six more months, or ensuring an election a couple of months earlier. If that was the reason, the government and its partners would have carried on till early next year, and the NDA would have simply waited for the anti-incumbency wave to gather force.

All the murkiness and trivialities apart, this crisis has been caused by three differing worldviews of how India looks at the post-Cold War world, its own position and stature there, and what it needs to do to further its interests. It is the first time in our history that foreign and strategic policy has become such an issue. So far, these policies had more or less been run on the basis of a consensus, Nehruvian for most of the first 25 years after Independence, and then only moved further in the same direction by Indira Gandhi. There was no debate on India’s prominent role in the non-aligned movement which tilted distinctly towards the Soviet Union, the underdog in the Cold War. This larger formulation was not challenged politically even when India took positions on the pulverisation of Hungary, Czechoslovakia and then Afghanistan, over almost three decades. Barring the hiccup of the 1962 defeat when the Nehruvian foreign policy paradigm was questioned, there wasn’t much doubt even on our policy on our borders, neighbours, and nuclear weapons.

That is why, when the Janata came to power in 1977, Prime Minister Morarji Desai and his external affairs minister, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, made no major departure even from Indira Gandhi’s Emergency past, except, perhaps, that they hosted Jimmy Carter, the first American president to visit India in a very, very long time.

On our border disputes, that consensus is contained in two unanimous resolutions of Parliament, which, if followed in letter and spirit, would require us to raise armies to recover all captured territories from China and Pakistan. On the nuclear issue too, when Indira Gandhi conducted Pokharan I, the opposition mostly applauded. Similarly, on Pokharan II, Kargil and then Operation Parakram, the Congress more or less played along as a loyal and “consensual” opposition.

Also read: A government of the 38% people, by 38% of the people, for 38% of the people

All this changed with the nuclear deal. The old Holy National Consensus on foreign policy now ended and an entirely new debate emerged. Further, it was a debate among three distinct views, not just two. Let us try to describe these very briefly.

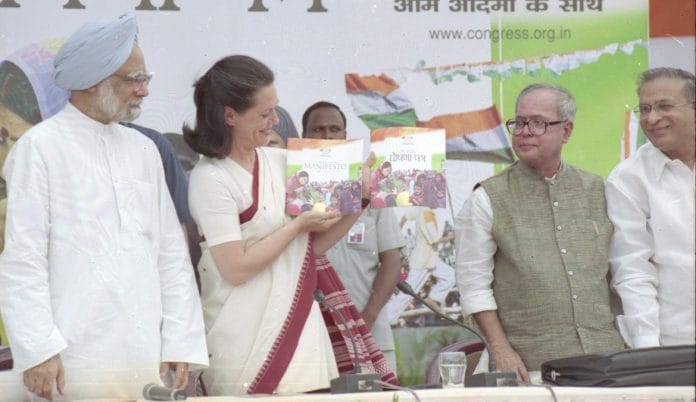

1. The first is the Congress-UPA worldview led by Manmohan Singh’s intellectual vision. The Cold War ended, and there is no doubt as to which side won. But this new, post-Cold War world is still figuring out its power balance and strategic architecture. This offers India enormous opportunities to leverage its geographic location, strategic muscle, economic strength and democratic, secular polity. India needs to be an equal member in multilateral negotiations and processes, have access to high technology denied it under various sanctions, and, most importantly, needs to settle its border disputes with Pakistan and China. All this, of course, requires friendly relations with America. Particularly, when the establishment in that country seems so favourably inclined towards us. This is where the nuclear deal came in. More than a deal for energy a decade from now, it was seen as signalling one great break from the America-phobic past. But, given the Congress party’s own Nehruvian non-aligned legacy, its political minds’ doubts about Muslim voters, this policy lacked conviction in its implementation, and even in its articulation. That is why this government found it so difficult to be fully upfront with the voters on the basis, wisdom and implications of this policy.

2. The BJP-NDA view is fundamentally not dissimilar to that of the Congress. But it is not encumbered by any nostalgia, emotion or, to put it more cynically, the risk of losing Muslim votes. It sees the US as a strategic ally, and explicitly says so. In fact, chances are that statement will be made in its election manifesto. It sees no problem, morally, strategically and even electorally, in being a partner of the US, holding military exercises, sharing information and strategising together. It follows that it is also not at all shy of an explicit and deep engagement with Israel which is something the Congress always handled very carefully. If the NDA comes to power, chances are that one of its senior cabinet ministers’ first foreign visits will be to Israel. The UPA has avoided that for a full four and a half years. This is why, while they may not disagree with the foreign policy paradigm shift that Manmohan Singh is trying to bring about, they do not necessarily see the nuclear deal as its touchstone. If they come to power, they and their coalition partners will be able to make other, even more radical moves in the same direction. So why not wait for a few more months?

On the borders, they do want to settle with Pakistan and China. But they see China as a strong, permanent strategic challenge. That is why they would prefer a larger nuclear arsenal, in a proper, old-fashioned triad, and even, ultimately, National Missile Defence. All this, in their worldview, is only possible in a tight, unambiguous and unabashed strategic alliance with the US. Manmohan Singh’s nuclear deal then looks like a small thing, and a bit of hypocrisy too.

3. The Left has always had a clear and distinct foreign policy view. While on many larger and conceptual issues they accepted the Nehruvian non-alignment, pro-Arab, pro-Soviet, wary-of-the-West formulations, they have always been against nuclear weapons or any strategic relationship with the US. But we did not hear too much of it in the past because the Left was not in the power structure. Now, and going ahead, particularly if another UPA government is installed with their support, or if their own third front succeeds this UPA, you need to understand their view as well.

As they look at the world, they acknowledge that the Cold War has ended and one side, possibly not the best side, has won. A single, dominant superpower creates a power imbalance and an unfair world. This must be addressed. The two powers in this transitional world that can challenge and contain the rise of one, dominant global bully are China and Islamic nationalism. One has already challenged Bush’s America, and the other, China, is getting ready. As and when China acquires that status, there will be a new balance of power, even if not a new cold war. In that situation the non-aligned movement will again find a raison d’etre. And when it does, India should be its natural leader. That will not only be sufficient to give India the stature it deserves in the new power architecture, it will also be more morally correct. Of course, this new non-aligned movement, like the last one, will be inclined more towards the underdog. They see the nuclear deal, therefore, as closing that option for India by linking it into a strategic relationship with America. And that they will not allow on their own watch.

Behind all the shenanigans and midnight deal-making, therefore, lies an entirely new debate in our domestic politics over foreign policy. It involves issues that will greatly influence the lives of our future generations, and hopefully the two-day debate next week will see each side argue its case before the nation. If this confidence vote becomes a seminal debate on India’s foreign policy, just as the 1999 debate (when Vajpayee’s government fell) became a landmark one on secularism, some good would have come out of this crisis.

Also read: Why India would do well with a coalition govt: Pro-poor policies, less inequality