I suspect each one of us who covered the anti-Sikh riots as reporters in November 1984 has a persistent nightmare. Some still wake up in cold sweat as images of half-burnt bodies in Trilokpuri appear again and again. Some cannot shake of the image of helpless widows, their men and children killed, their houses burnt, pleading for help from a police that only looked the other way.

I have a couple of mine, too. One is of defiance. A group of Sikh taxi drivers outside Imperial Hotel on Janpath decided to protect themselves as the state – South and North Blocks, Rashtrapati Bhavan and Parliament are less than a kilometre away – had chosen to abdicate all responsibility. They picked up chains, sticks, iron-rods, just stones and decided to take on the mobs. On the afternoon of November 2, I was with a small group of reporters that witnessed this remarkable incident.

A mob of several hundred would converge on the taxi stand shouting the by-now-familiar slogan: khoon ka badla khoon, Indiraji hum sharminda hain, tere qatil jinda hain (blood for blood, Indira we are ashamed, your killers are alive). But the small group of taxi drivers, instead of fleeing, challenged them with what looked like a whole motor workshop converted into an armoury – they had even plucked out fenders from their Ambassadors.

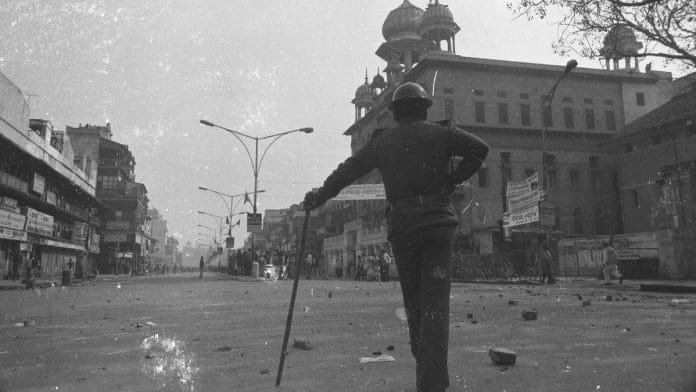

A dozen assaults were mounted, each was beaten back and soon enough many helpless bystanders, including us reporters, were cheering. All it took were a few brave men to keep at bay a mob of the kind that was looting, pillaging and killing in many parts of the city, unquestioned, unchallenged and often helped by a police force that looked more complicit than even Modi’s in Gujarat, 2001. In Gujarat, at least the police opened fire several times, killing Hindus and Muslims. Here you found Delhi policemen openly talk of the need to teach the Sikhs a lesson. Only in Paharganj did we see some police firing.

But, as it turned out, the story here was that some armed Sikhs (“Khalistani sympathisers”) were apparently hiding in a house. So, two groups of Delhi policemen and one of CRPF were firing at it. It was so farcical, entirely comical – except there was a real fear of some reward-seeking policemen getting caught in this competitive friendly fire.

My other nightmare is a beautiful house at the corner of Chirag Dilli and Panchsheel Park, next to where the flyover came up later. The house burnt furiously as perhaps no other, even in those three days of arson. There was no provocation, just that word had spread that it was owned by a Sikh family. The family, fortunately, escaped the mobs. But the looted house, set on fire, lit the night brutally in what you thought was safe, upper-crust South Delhi. The mobs, on the other hand, had just realised that while there were easy killings available in poorer, more congested, areas, real “value” in terms of loot, was in well-to-do areas.

Also read: Congress was involved in 1984 anti-Sikh riots – I saw & reported it

I remember that burning house, the towering column of smoke that dominated an already blackening sky, as I drove past it on my Enfield one afternoon, riding the pillion behind me two neighbours, India Today colleagues, one of them expecting her first child soon, as we were expecting our second. Both our boys are twenty now, and final year college students. They represent a whole new generation of Indians born after that dreadful tragedy which has already voted in one state and one national election. But those that suffered in those 72 hours of hell are still awaiting justice.

Those that were responsible for it have still escaped the supposed long arm of justice, or retribution. That burning house is my most persistent nightmare. It was never rebuilt. It was believed the owners sold it and migrated to Punjab. Or at least, that is what was believed rather easily at that point in a city dominated by people who had already seen one Partition.

Partition, in fact, was the dominant metaphor in the rumour mill. Your next-door neighbour would tell you of trains loaded with Hindu bodies coming in from Punjab. There was talk of mass rape and mutilation of women. Then you asked a few questions on the source of the rumour and the answer usually was, “I didn’t see, but my brother saw a train, or probably my brother’s friend’s neighbour”. There was no truth in any of them. No such thing even happened. And truth to tell, even the most vicious rumours never succeeded in turning Hindus against their Sikh neighbours.

In one colony after another, you saw vigilante patrols at night with residents carrying hockey sticks, cricket bats and even shotguns, not to ward off any attacks from marauding Sikhs but to protect their own Sikh neighbours. Ordinary people like us in middle-class localities ignored all rumours and maintained peace. Even when Delhi Police officially joined the rumour business by giving currency to wild rumours that Sikh militants had poisoned water supplies. In many areas we saw police vans making announcements asking people to avoid municipal water that may have been poisoned.

These were no communal riots of the kind you often see, or saw in Gujarat, where neighbours turn on neighbours. In every locality, from tony Panchsheel Park to the Govindpuri slum, the killer mobs came from elsewhere. Somebody had got them together, told them where to go and target the Sikhs. Most important, they were promised the police won’t interfere. And that was a promise Delhi Police kept for a good 72 hours.

I remember driving around Govindpuri on my motorbike, skirting burning bodies, a hundred fires, big and small, raging around the place, and at the local police station they told you nothing had happened, nobody had died, everything was in control. Or the odd policeman would chide you. What’s wrong with you presswallas? Are you Khalistani sympathisers? Reporters like me had limitations in terms of how extensively one could document all this because I then worked for a fortnightly (India Today). But several newspaper reporters, notably Rahul Bedi, Sanjay Suri and Joseph Maliakan of the Indian Express, did a stellar and courageous work tracking and documenting this, day after day. Without their contribution, so many inquiries and commissions would have failed to name even these few names.

The points that intrigued me for a long time afterwards were, if mobs had all come from “elsewhere”, who were these people? Who got them together, and what was in it for them? Finally, how did the killings stop abruptly? It was clear soon enough that the mobs comprised mostly jobless lumpens, collected by political mafiosi on the promise of easy loot and pillage. One of the most shameful chapters in that story was how Delhi Police, under pressure a few days after the riots, declared a ‘voluntary disclosure scheme’ whereby you could bring back any goods you may have looted and deposit them in a police station with no questions asked.

The killing, however, stopped all of a sudden, the moment a few army APCs appeared. No mobs fought with the army, there was very little firing. Just the message that the army was out and police “protection” no longer available now, and the mobs lost their will. It was, after all, not like the Partition, or even Gujarat, 17 years later. This was not the case of a community turning on another in blind fury, willing to face bullets, lathis, anything. This was “good-time” mobs who melted away the moment they saw some challenge.

That is why those of us who covered the riots, and many more who carried out relief or citizens’ investigations subsequently, generally believe that what we saw over those murderous 72 hours were not Hindu-Sikh riots but Congress-Sikh riots. Or, rather, Delhi Congress-Sikh riots. Too many small time Congress politicians, who had built their careers organising crowds for Sanjay and then Indira Gandhi, decided revenge was naturally expected of them. So what is the difference between collecting an Emergency-type crowd to chant slogans in support of the 20-point programme, or a pogrom of the Sikhs which also brought the promise of loot?

If there is one thing that has emerged with the Nanavati Report and its aftermath, it is that political parties have to accept their past will continue to come back and haunt them. They cannot, as in the past, use brute force to sweep all questions under the debris. The Congress is not the only party to have done so. If Advani and Vajpayee, after making such solemn speeches last week, recall what their own party did with the Srikrishna Commission in the Bombay riots of 1992, they will be ashamed too. And, hopefully, they will remember that when Justice Nanavati delivers his findings on Gujarat, 2002.

Also read: On his death anniversary, remembering the most interesting man I’ve met: Bhindranwale