Concerns remain about the safety of disrupting or repairing defective genes, but experts say they are not a ‘show-stopper’.

A pioneer of the Crispr gene-editing technology that’s taken Wall Street by storm says the field is probably five to 10 years away from having an approved therapy for patients.

Biochemist Jennifer Doudna, who runs the Doudna Lab at the University of California at Berkeley, says major questions remain about the safety and effectiveness of experimental therapies that aim to disrupt or repair defective genes. But she’s optimistic about their prospects.

“Can we today edit the DNA in human cells? Yes. Can we do it accurately? Yes. That’s absolutely being done in many labs around the world now,” Doudna said in an interview on the sidelines of a gene-editing summit at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. “But the challenge is how to think about moving that into a clinical setting.”

It’s not going to be an easy task, the researcher acknowledges, but “many of us feel so excited about the opportunities, that there’s a lot of motivation both on the part of academic scientists as well as companies to figure out the steps that will make that possible.”

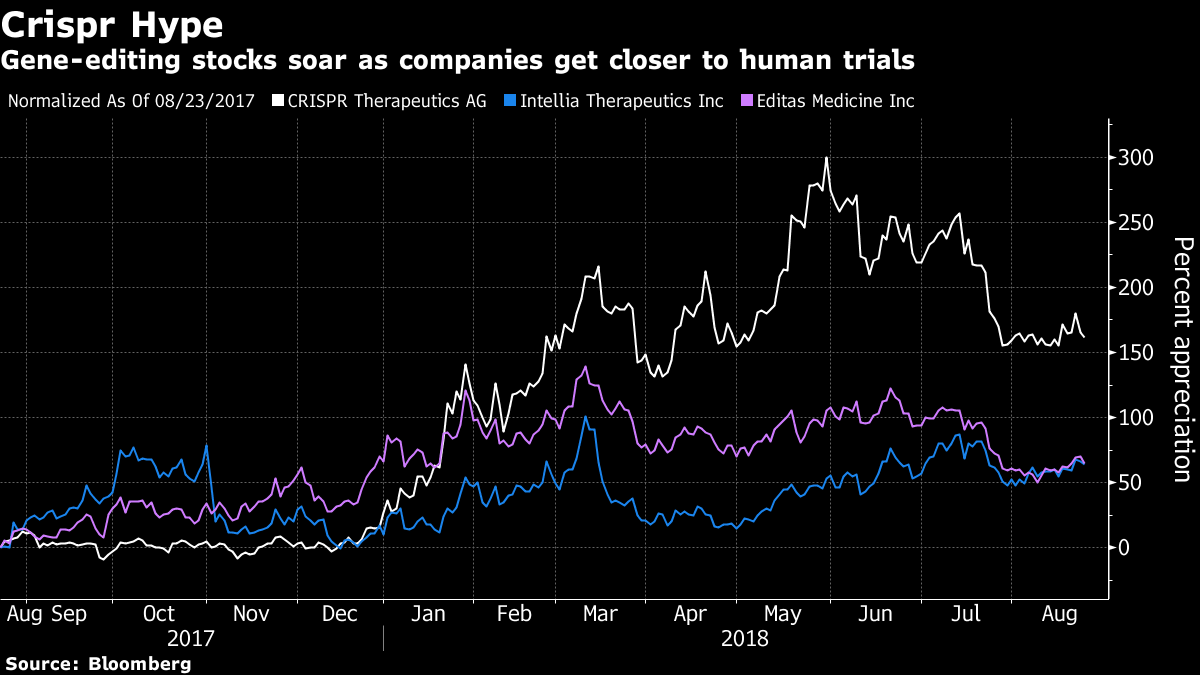

Three public companies leading efforts in the space — Crispr Therapeutics AG, Editas Medicine Inc. and Intellia Therapeutics Inc. — have seen their shares skyrocket over the past year before dosing even a single patient in a trial. Citi analysts have forecast the global market for Crispr technologies may reach $10 billion by 2025.

Goldman Sachs analyst Salveen Richter, who has the highest price target on Crispr Therapeutics — the first U.S.-traded company expected to start a human trial — sees approval for its beta-thalassemia therapy as early as 2022 in Europe, and 2023 in the U.S.

As the company prepares to begin studies in Europe and Canada later this year, while awaiting U.S. regulators’ approval, a number of scientific publications have sounded alarms about potential risks, including cancer-causing mutations.

Doudna, a co-founder of Editas and Intellia and other Crispr startups, says the findings aren’t surprising because gene editing is “intrinsically an error-prone process” that doesn’t always work in the desired way.

She cautions, however, that it’s hard to know how those lab results will translate into clinically meaningful data. “It’s an important reminder that we need to be careful,” she said. “But I don’t see anything that, to me, would be a show-stopper here.”

China appears to be leading the Crispr race, having already edited genes in dozens of patients, the Wall Street Journal reported earlier this year. In the U.S., the University of Pennsylvania is recruiting sarcoma patients for one of the three arms planned for an early-stage study, according to a Penn Medicine spokesperson. Doudna, who has been a leading supporter in raising awareness and debating the ethics of Crispr, is helping organize the second international conference on gene editing in Hong Kong this fall.

The University of California, Doudna’s academic home, and Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University are awaiting a decision from an appeals court in Washington over questions of who is entitled to patents and thus can profit from Crispr technology. Doudna says it’s been “frustrating” to see the amount of money and time that has been spent on the patent dispute.

If it ultimately comes down to opening lab books, the scientist says she’ll be delighted. “If anyone wants to do that, we’re ready.”-Bloomberg