The word “cancer” itself is enough to evoke terror, with global incidence of the often-fatal disease on the rise: From 14.1 million in 2012, the number of cases had risen 20.6 per cent to 17 million in 2018.

But the disease is no longer the death sentence it once used to be. According to the American Cancer Society, the five-year survival rate of breast cancer patients in 1975-77 was 75 per cent, but this had risen to 91 per cent between 2006 and 2012, a trend also seen in many other types of cancer.

At the heart of this progress is greater public awareness, and advancement in early detection and therapeutic approaches.

Traditionally, most cancers are treated with radiation therapy, chemotherapy and surgery, or some combination of the three.

While these treatments have proven to be useful and continue to be improved, they have fallen short of treating some of the most aggressive cancer types [lung, brain, pancreatic, and triple negative breast cancer, which can be more aggressive to treat].

In addition, radiation and chemotherapy have side-effects, like oral sores, weight fluctuations, hair loss, fatigue, and flu, that can be debilitating for patients.

Researchers are constantly working on novel therapeutic options to treat cancer and, in recent years, new approaches have emerged that address these shortcomings.

One of the most eagerly-watched lines of treatment has been immunotherapy, which involves priming the immune system to eliminate cancer cells.

Although the concept of immunotherapy has been around since the 1900s, its application in clinics is recent. It has shown great promise in the targeted killing of cancer cells, thereby greatly improving overall patient well-being.

No longer a ‘death sentence’

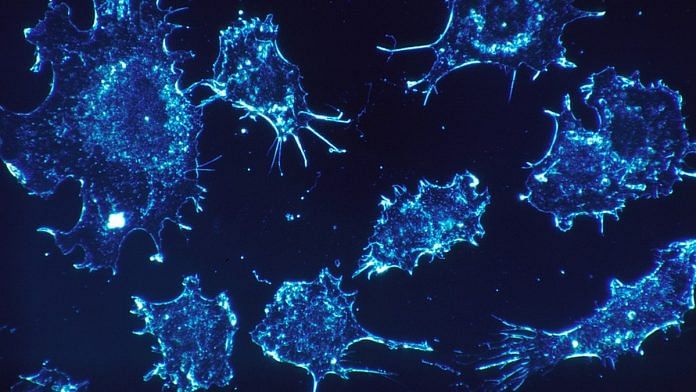

Cancer occurs when some cells in the body divide in an unregulated manner, leading to an accumulation of cancerous cells that may even migrate to other parts of the body.

One of the reasons a tumour cell thrives in the body is because it can evade the patient’s immune system, which is designed to recognise foreign/unwanted entities and eliminate them.

In some cases, the immune system may begin to mount a response, but the cancer cells adapt and cause the immune system to get exhausted. Immunotherapy aims to reverse this by turning its guns specifically on cancer cells.

It involves the use of drugs to empower the body to fight cancer by stimulating the patients’ immune system to identify tumour cells, and then eliminate them.

There are different types of immunotherapy being developed.

1. Monoclonal antibody therapy: Monoclonal refers to the process of asexually-deriving clones from a single individual or cell. Antibodies are blood proteins produced by immune cells that specifically bind to and neutralise foreign bodies or antigens.

In monoclonal antibody therapy, antibodies meant to target cancer cells are designed and manufactured in a lab and injected into patients.

They are built in a way that they recognise an antigen on cancer cells and specifically target it, stopping the cells from growing and significantly reducing tumour size. They do not attack healthy cells, thereby reducing the probability of grave side-effects. This therapy has shown tremendous success in the treatment of breast cancer with the expression of the HER2 protein.

2. Checkpoint Inhibitors: This type of drug stimulates the host immune system to recognise tumour cells and destroy them. It relieves the “brake pedal” from T-cells (white blood cells that form the chunk of the immune system), allowing them to attack and kill cancer cells.

The most important checkpoint inhibitors, like the ones for PD1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 proteins, were identified by researchers Tasuku Honjo and James P. Allison, with the discovery winning them the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

According to the American Cancer Society, these drugs have been shown “to be helpful in treating several types of cancer, including melanoma of the skin, non-small cell lung cancer, kidney cancer, bladder cancer, head and neck cancers, and Hodgkin lymphoma”.

3. Adoptive Cell Therapy: Better known as CAR T-cell therapy. In this line of treatment, T-cells from a patient’s body are harvested and grown in large batches in the lab. The T-cells are modified to enhance their ability to mount a response against cancer. Once enough T-cells are obtained, they are injected back into the patient, which boosts the ability of their immune system to fight cancer cells.

This treatment has proved successful in hard-to-treat cancers like leukaemia and lymphoma.

4. Cancer vaccines: In this approach, antigens from a patient’s cancer cells are extracted in the lab and then injected back in. This primes the immune system to kill the tumour cells and reduce the tumour size. This approach has been successful in treating prostate cancer.

Also read: European regulator finds cancer-causing element in diabetes medicines made in India

Still under research

Immunotherapy is still a relatively new step in the direction of cancer treatment, with more research underway. The United States, for one, has been an early adopter of immunotherapy.

In 2015, the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA), the watchdog for public health, approved the first immune checkpoint inhibitor as the maiden line of treatment for non-small cell lung cancer.

A year later, an immune checkpoint inhibitor for lymphoma, head and neck cancers, and bladder cancer was cleared as well.

In early 2019, the US FDA approved an immunotherapy regimen in combination with chemotherapy for breast cancer treatment.

In a clinical trial last year, chemotherapy and checkpoint therapy together helped breast cancer patients suffering from a severe form of the disease ensure a progression-free survival (decrease/no increase in tumour size) of 7.2 months, compared with 5.5 months for women who received chemotherapy alone.

The overall survival improved from 17.6 months, with chemotherapy alone, to 21.3 months with chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

In another study, 16 per cent of patients suffering from advanced lung cancer and treated with a checkpoint inhibitor lived for five years after treatment, compared to only 4 per cent of those who received chemotherapy alone.

The patients involved in the studies suffered fewer and easier-to-manage side-effects than those seen with chemotherapy and radiation, including headache, swollen legs, cough, and sinus congestions.

Most cancer hospitals in the US have specialised immunologists that work in collaboration with physicians to create treatment plans for patients. India, meanwhile, has shown cautious optimism in the adoption of immunotherapy.

One potential hindrance for immunotherapy adoption may be the lack of Indians-centric clinical trial data. To remedy this, a clinical trial focusing on Indian patients with head and neck cancers, bladder cancer, lung cancer, and renal cancer was recently concluded, its resulting study published on 1 June last year.

The results were encouraging, with researchers concluding that “immunotherapy is feasible option for treating advanced lung, head-neck and urothelial/renal cancers with acceptable toxicities”.

In 2017, India approved one of its first checkpoint inhibitor drugs that targets aggressive, difficult-to-treat lung cancer.

Currently, there are four checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer that are approved by the Drug Controller General of India.

Success stories of immunotherapy have begun to emerge. In one case, an immunotherapy treatment regimen proved successful for a stage-four lung cancer patient at Sahyadri Hospital in Pune — this patient was in remittance for 12 months and did not experience significant side-effects, according to a November 2018 report published in The Times of India.

India is still a growing market, where the infrastructure for large-scale production of immunotherapy drugs has not been set up.

Efforts are being made in this direction and, last year, Indian clinicians and scientists set up the Immunological Society of India at Tata Memorial Centre in Mumbai with the goal to advance immunotherapy research and treatment, and also lower the cost of treatment.

Additionally, in collaboration with IIT-Bombay, a patent for a variant of CAR T-cell therapy has been filed and the plan is to start clinical trials at Tata Memorial Hospital. The aim is to provide this treatment option at a much-reduced cost than what is charged at US hospitals.

Atul Khire and Pooja Panwalkar are postdoctoral scientists working in the field of drug discovery and cancer biology. They can be reached at Atul Khire (Twitter ID: @pipetterinchief) and Pooja Panwalkar (Twitter ID: @postdockin).

The views expressed belong to the authors. The article is not medical advice, and in case of any questions/doubts, readers are advised to seek medical opinion from a clinician.

Also read: Now, a cancer-causing substance found in Johnson & Johnson’s ‘No More Tears’ baby shampoo

Excellent article. Many thanks.