Madhubani/Patna: Three days before Madhubani goes to the polls in the second phase of the Bihar elections, the otherwise-bustling bazaar in Bhairwa village at the Bisfi assembly constituency is nearly empty.

“We are all heading for (Samajwadi Party chief) Akhilesh Yadav’s rally,” says a visibly impatient 65-year-old Hasnain Sheikh. “You will not find anyone to talk to in the village right now.”

An hour later, amid dust swirling in the late afternoon light, a crowd of men wearing green Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) scarves—draped around their necks or tied as turbans—is on its way back from the rally on four-wheelers, bikes, bicycles, and on foot.

Songs celebrating Yadav pride blare from the speakers of passing vehicles. Meanwhile, buffaloes push their way through the returning crowd. The narrow lanes of Bhairwa are choked.

“You know how you can tell the difference between young Yadav and Muslim boys from the crowd?” Sheikh asks, as he too returns. “All the flamboyant, assertive faces on the bikes are Yadav. The faces of the Muslim boys are subdued,” he says thoughtfully.

“Both will vote for the RJD, but their hopes from RJD rule are entirely different,” he adds. “Ek ki dabdabe ki ladai hai, aur doosre ki jeene ki (for one, it is a fight for pride, for the other, it is a fight for survival).”

Across the state, ask Muslims what the issues on their minds this election are, and the initial responses are standard: development and jobs—abstract, vacuous ideas tossed around airily by voters and leaders alike.

But a couple of follow-up questions reveal the deep fears and anxieties gripping the community, which forms 17.70 percent of Bihar’s population.

The spectre of disenfranchisement, deportation and demolitions looms large. Add to this, the extreme poverty and social backwardness of Bihar’s Muslims—a socio-economic survey of Muslims in the state conducted in 2001 found that 49.5 percent of the rural Muslim households and 44.8 percent of those in the urban areas live below the poverty line—and you have a community teetering on the brink.

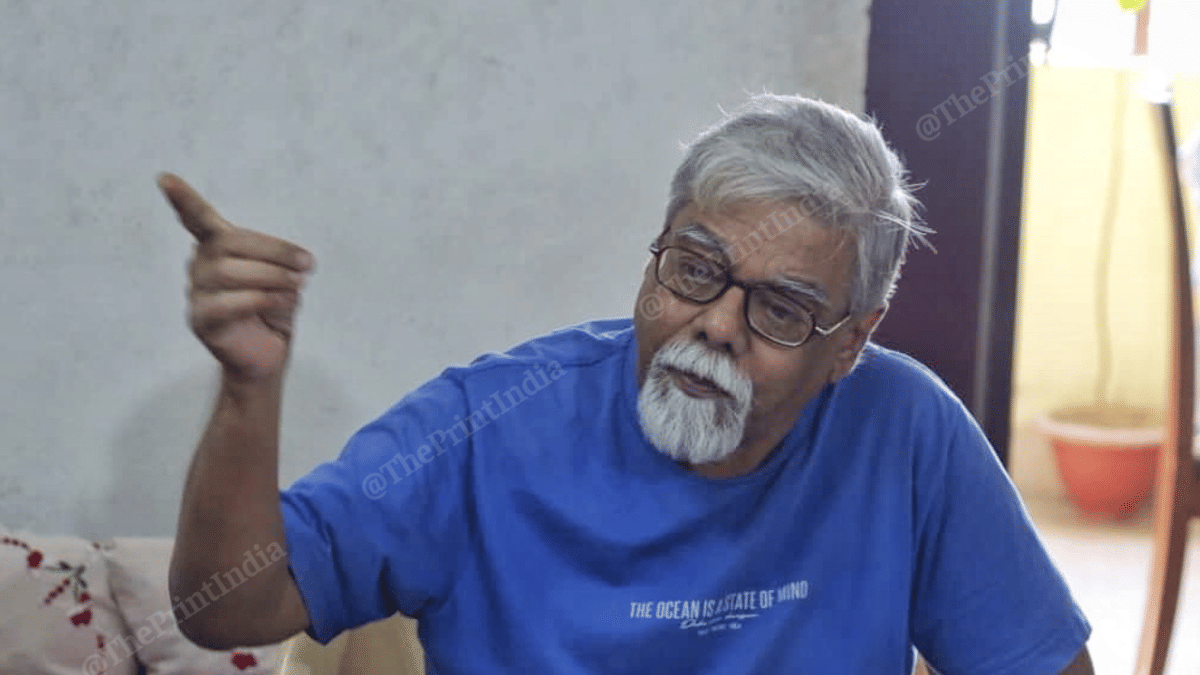

“Throughout independent India’s history, Bihar’s Muslims have voted for whoever has guaranteed them security,” says Safdar Imam Qadri, the Head of the Urdu Department at the College of Commerce, Arts and Science in Patna.

“This has been the tragedy of Muslim politics—from the time of Partition, it has seldom risen above the politics of physical safety. Be it the Congress or the RJD, the Muslims rally behind whoever promises to keep them safe,” he adds with a resigned smile. “How can there be political consciousness without physical security?”

Yet during brief interludes of communal peace when the community has felt secure, it has, much like the rest of Bihar’s polity, displayed striking political awareness and aspiration. From the Urdu Aandolan of the 1960s to the Pasmanda Movement of the 1990s, Bihar has been the crucible of a democratically assertive and introspective Muslim politics.

As Bihar votes in the second phase on Tuesday, polling will also take place in the Muslim-dominated Seemanchal region, which includes Kishanganj (68 percent Muslim population), Katihar (45 percent), Araria (43 percent), and Purnia (38 percent).

ThePrint looks at the layered landscape of Muslim politics in the state, often reduced to voting patterns within the community.

A bulwark against Muslim League

One of the enduring enigmas of Bihar’s political landscape is its relative resistance to religious polarisation—especially when set against the volatile backdrop of neighbouring Uttar Pradesh. The state’s grinding poverty has often been invoked as a ready explanation. “Bihar is just too poor to harbour communal enmities,” runs the familiar refrain.

While true to an extent, the explanation does not factor in the fact that, unlike the Muslim elite of UP, their counterparts in Bihar had historically been trenchant critics of the Muslim League and the idea of the Partition.

The strongest articulation of this critique came from Bihar’s Imarat-e-Shariah (which literally means “the governance or leadership of Islamic law”).

Founded by Maulana Abul Mohasin Mohammad Sajjad in 1921, the Imarat-e-Shariah always opposed the League and its “communal agenda”. Even when he got disillusioned with the Congress, Maulana Sajjad formed a party of his own, the Muslim Independent Party (MIP)—which formed the government in Bihar in 1937—rather than join the League.

In 1940, Maulana Sajjad delivered a biting critique of the All India Muslim League’s Lahore Resolution, which demanded the creation of “independent states” in the northwestern and eastern zones of India, where the Muslims were in a majority.

“Regarding the Muslims of Hindu-majority regions, Jinnah only says that the Muslim majority provinces will be a guarantee to the rights and interests of the Muslims of Hindu majority provinces (aqalliat subahs). What it implies is that if some oppression against the Muslims in Hindu-majority regions takes place, the Hindus of Muslim majority provinces will be subjected to oppression in retaliation. This kind of barbarity can be perpetrated only by a fool (Ahmaq) or insane (Majnun),” he wrote.

But he was no advocate of the Congress either, which he referred to as “communalist to the core”.

There was another political grouping in pre-independence Bihar that was vehemently opposed to the Muslim League, but also kept the Congress at bay, said Qadri.

“As early as 1911, the All India Momin Conference of the Ansaris and the Momins was formed to represent backward Muslims,” says Qadri. “They said unambiguously that the League is an organisation of upper caste elites, and does not represent the interests of backward Muslims at all,” he said.

Post-independence, the Momin Conference always found robust representation in Congress governments, he added.

“The point is that Muslim politics of Bihar itself had always been stridently non-communal and nationalist to the core,” he explains. “So, it is only partially correct to attribute the relative calm of Bihar to the economic impoverishment of both communities.”

Despite the clear preference of much of Bihar’s Muslim elite for a united India, by 1946 the province was engulfed in communal flames.

“When the Noakhali riots erupted in Bengal, the Hindu Mahasabha and the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) began clamouring for revenge here in Bihar,” recalls Qadri. “There was sheer mayhem.”

From June to October 1947, Mahatma Gandhi camped in Patna and conducted sarvodharma prayers every evening. Thousands would descend every day to what were then called the ‘Patna Lawns’ to listen to his message of peace and communal harmony.

Three months after he was assassinated on 30 January 1948, ‘Patna Lawns’ were renamed the Gandhi Maidan—the iconic gardens which have witnessed the making of not just Bihar’s but India’s political history over the decades.

“This is how intertwined Muslim politics is with the politics of Bihar,” says Qadri.

Also Read: Between idealism & survival: The Left’s long life in Bihar & its electoral pragmatism

Post-Independence years

Post-independence, the Muslims in Bihar, like the rest of India, had lost the one important battle that could assure them political representation in a partitioned India—the battle for separate electorates.

Moreover, the Muslims at large were viewed suspiciously for purportedly supporting the Partition of India and raising the demand to make Urdu an official language. The Muslims, in turn, were gripped by the fear of the rise of the Hindu nationalist forces and communal riots. As a whole, the community moved to the Congress, hoping for state protection.

“During the first few decades, this arrangement continued,” says Satya Narayan Madan, a veteran socialist activist. “Like most others, the Muslims supported the Congress, and were a crucial component of its support base, alongside the upper castes and the Scheduled Castes.”

“The Congress even made Abdul Ghafoor a Muslim chief minister of Bihar (in 1973),” he adds. “He was not a leader of the Muslims as such, but that was a time when at least the politics of Muslim representation existed.”

Moreover, Muslim politics, Madan says, hinged on the politics of protection. As long as the state provided protection to Muslims under the Congress, the Muslims stayed with the party.

During this period of protection and calm emerged the Urdu Aandolan—the movement to make Urdu a state language started once again.

“Whenever there have been periods of communal calm, Muslim politics in Bihar have evolved meaningfully,” says Madan. “In fact, in these decades, an Urdu public sphere flourished in Bihar, as opposed to Uttar Pradesh.”

Led by Ghulam Sarwar, a politician and journalist, who also became the education minister in the Karpoori Thakur government, the Aandolan had several tangible achievements.

As noted by Mohammad Sajjad in his book ‘Muslim Politics in Bihar’, it was in this phase that the Urdu Academy was established (1973), the Bihar State Madrasa Education Board came into existence with statutory strength (1978), and a large number of Urdu-medium schools were established by the government.

In 1977, he succeeded in making Urdu the second official language in Bihar in 15 districts—the impact was both symbolic and substantive. All government hoardings in Bihar now carried their messages in Hindi and Urdu.

FIRs could be filed in Urdu. Government applications could be made and responded to in Urdu. Jobs for Urdu speakers opened up—assistant translators, translators and Raj Bhasha assistants—were hired in thousands.

“Such constructive politics was happening at this time only because the Muslims were relatively secure, and could expand their political rights,” Madan explains.

By the end of the following decade, this peace, and the politics of expanding the democratic rights of Muslims, came to a violent halt.

The end of a contract

On the day of Moharram in 1989, the Superintendent of Police (SP) of Bhagalpur, K.S. Dwivedi, delivered an inflammatory speech. Bhagalpur would be turned into Karbala—a chilling insinuation that there would be a massacre of the Muslims in the town. On the ask of the district magistrate of the time, Dwivedi was forced to apologise.

However, days later, his ominous prophecy came true. Bhagalpur, indeed, was turned into Karbala. Several accounts of victims accused Dwivedi of not just looking the other way when violence was unleashed on them, but actively using state machinery to target the Muslims.

When Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi landed in Bhagalpur, he ordered Dwivedi’s transfer. The cadres of the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) and the Bajrang Dal were up in arms. Under pressure, Rajiv reinstated Dwivedi and left Bhagalpur.

A more vicious, staggered cycle of violence ensued. A government inquiry into the riots, which left over 1,000 Muslims dead—Qadri recalls the riots as another Partition, after which entire villages were abandoned by Muslims—noted that Dwivedi was “wholly responsible” for the carnage.

“His communal bias was fully demonstrated by his manner of arresting the Muslims and by not extending adequate help to protect them,” the report noted.

The unsaid, but foundational contract between the Congress and the Muslim community was irrevocably broken. The state’s promise of security to the community, which had opted to stay back after the Partition, was egregiously broken.

This came close on the heels of the Rajiv Gandhi government’s decision to open the locks of the Babri Masjid to allow the Hindus to worship at the site just a few years ago in 1986.

If the Congress has failed to form a government in Bihar by itself after 1989, one of the key reasons is that, since then, the support of the Muslim community has almost entirely eluded the party.

The messiah arrives

“I was in Ranchi when the Babri Masjid was demolished in 1992,” says Kanchan Bala, a seasoned socialist activist. “I knew things could go bad. I wanted to return to Patna as soon as possible, so I went to the Commissioner there, who I knew well.”

“I must have sat with him for a couple of hours. And every few minutes, he would receive a call from Lalu asking for updates, giving orders about police deployment, etc… Lalu was monitoring the situation like a commander on a battlefield,” the septuagenarian recalls. “And that is the reason when the whole country was up in flames, Bihar remained an island of calm.”

“Today, everyone assumes that Lalu has the trust of the Muslim community no matter what happens, but few see how arduously he won that trust,” Bala says.

By 1990, the Congress’s long-standing coalition of upper-caste, Dalit and Muslim voters, which had sustained its dominance in the state for decades, had finally disintegrated.

Besides, the Backward vote came to enjoy unparalleled primacy in electoral arithmetic. By combining the Backward support with Muslims—which added up to almost 40 percent of the vote—Lalu had discovered an invincible winning formula.

Lalu was not just a passive benefactor of the Muslims. As soon as he rode to power, he was willing to demonstrate his commitment to the community’s security.

In September 1990, Lal Krishna Advani, the then president of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), was in Bihar on the penultimate lap of his Rath Yatra from Somnath to Ayodhya. Wherever the Yatra went, it left behind spectres of religious frenzy.

For too long, the V.P. Singh government at the Centre had allowed Advani, on whose party Singh’s “secular” government depended, to move ahead. But the Yatra was now at Ayodhya’s doorstep. Advani had to be stopped. Singh summoned Lalu to do the job. On the night of 22 October 1990, the BJP leader was arrested in Samastipur.

Overnight, Lalu jumped to the national limelight—the bulwark against communalism, the man who dared to stop Advani.

As journalist Sankarshan Thakur wrote in ‘The Brothers Bihari’, “He became the darling, at once, of Muslims countrywide, and of the Left-wing intelligentsia: the gallant saviour of the downtrodden and the minorities.”

“Nobody should dare spread communal tension in Bihar or he will be severely dealt with,” Lalu declared as he went around Patna on his own Sadbhavna Rath. “I have the courage to arrest Advani; I will be unsparing in my punishment.”

Just before the demolition of the Babri Masjid, when violence broke out in Sitamarhi in October 1992, Lalu was in the town within hours of the first report of violence, transferring officials, and personally monitoring the situation.

“Again, he was like a hawk,” says Bala. “The message was loud and clear: Under Lalu Raj, the Muslims are going to be safe.”

Also Read: Karpoori Thakur: The convenient resurrection of Bihar’s Jannayak

Beyond security

The Lalu years were a period of communal calm—a conducive time for community introspection.

In 2001, the Lalu government commissioned a survey on the socio-economic status of Muslims in the state. Its findings were discomfiting. After more than 10 years of the Lalu rule, the community was struggling to make ends meet. Almost 50 percent of the rural Muslim population (87 percent of the Muslim population in Bihar at the time lived in the rural areas) lived below the poverty line.

Only 35.9 percent of the rural Muslim households possessed any cultivable land. The corresponding figure for the general rural population was 58 percent. For about one-fifth of the land-owning Muslim households, the amount of land was so marginal that they had no option but to lease it out to cultivators with larger land holdings.

Death rates were higher, and life expectancy rates, lower than the rest of the population. Though Muslims constituted about 16.5 percent of the population, only 1.5 percent of rural households and 1.8 percent of them in the urban areas had a member participating in the panchayat or municipality administration. While their participation in educational institutions was slightly better, it was largely confined to madrasas, the survey noted.

Clearly, under Lalu Raj, the community could have security, but not much else.

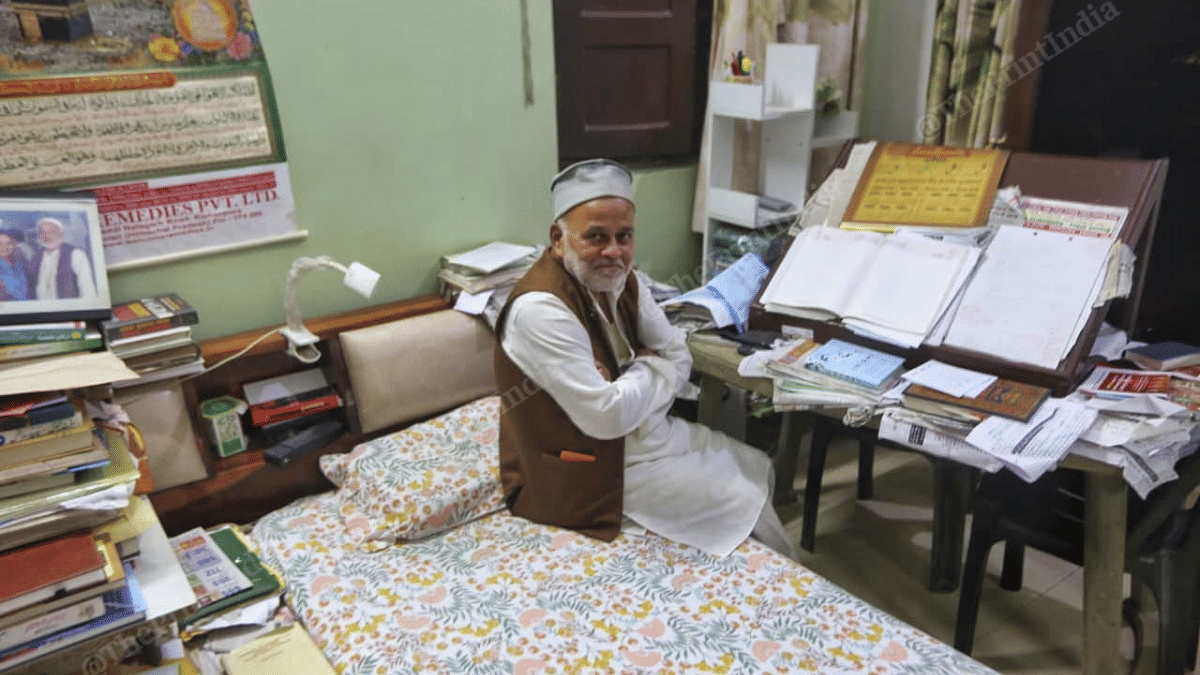

“Throughout history, the Muslims represented by ‘secular’ parties have been privileged, upper-caste, well-off Muslims, who share nothing in common with the backward masses of the community,” says Dr Aijaz Ali, a Patna-based surgeon, who started the Backward Muslim Morcha in 1994.

“My movement’s agenda was clear: there should be a category of Dalit Muslims, who should have the same rights as Hindu Dalits. If Lalu was such a messiah, why did he never act on this?”

Among the Muslims, Ali says, a large majority belong to the Pasmanda or backward castes—a finding corroborated by the 2023 caste survey, according to which 73 percent of the Muslim population in Bihar is Pasmanda.

“There are among the Muslims, dhobhis, Nats, banjaras, halakhors, bhangis, mochis, pasis, julahas, idrisis—but these upper-caste Muslims will say, ‘Sahab, there is no caste in Islam’,” Ali says.

“They thrive because of the communal narratives, which help maintain unquestioned leadership of the community—the Dalit Muslim is actively suppressed from asking for anything more than physical security.”

“It is with these caste-denying upper-castes that the likes of Lalu share power. For the Dalits, they have nothing to offer,” he argues.

Chipping away

By the 2000s, change was quietly rippling across Bihar. After a decade in power, it had become clear that what had been touted as Mandalization of politics was only its Yadavization.

As Nitish Kumar began jostling for power, he did so by “nibbling at the Mandal fencing” Lalu had carefully erected. To chip away from older classifications, Nitish created new sub-classifications—the Mahadalits and the Extremely Backward Castes (EBCs). He did the same with Muslims—thereby “secularising” Muslim politics.

He cleaved backward Muslims from the landed Sheikhs, Sayyids and Pathans, and as Thakur said, “Mandalized Islam”.

For the first time in the history of Bihar, the Muslims were promised something more than the representation politics of the upper-caste Muslims, Ali says.

“Under the Nitish Kumar government, actual, tangible things were done for Muslims. He brought about a law to fence graveyards to prevent encroachments; he gave madrasa teachers pay parity with other school teachers, started Taleemi Markaz, i.e., education at the doorstep, by holding classes for groups of 10-15 children at their doorstep in order to spread education in the community,” says Ali.

“His vision for Muslims was constructive, and that is why he was able to take away a chunk of Muslim vote from Lalu.”

Like Lalu before him, Nitish, too, offered the Muslims the assurance of safety. In 2013, as Narendra Modi’s star rose swiftly within the BJP, Nitish staged a dramatic parting of ways with the National Democratic Alliance (NDA).

“To govern a country like India, you have to take everyone along; sometimes you will have to wear ‘topi’ and sometimes ‘tilak’ (kabhi topi bhi pehenni padhegi, kabhi tilak bhi lagana padega),” Nitish said that year, keen to project himself as the moral counterpoint to Modi.

Politics of survival

“Nitish Kumar is like Vajpayee,” says Abdul Qalam, a 57-year-old garment shop owner in Bhairwa. “He manages to maintain this secular image, and then backstabs Muslims. This time, it is a vote to survive or perish for us…We will not waste it,” he says, alluding that there is going to be much cohesion in the Muslim vote this time.

Over the last few years, as Nitish has chosen to ally with the NDA under Modi, support the government’s controversial amendments to the Waqf Act, look the other way on issues of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), etc., the section of Muslims who had come to support him have moved back to the RJD, argues Qalam.

Across villages in Bihar, Muslim migrants have returned in large numbers this time to cast their vote.

“It is a vote under fear. Everyone feels that if they don’t cast their vote this time, their names might just get removed from the voter lists,” says Qalam. “That is why the vote percentage this time has been high.”

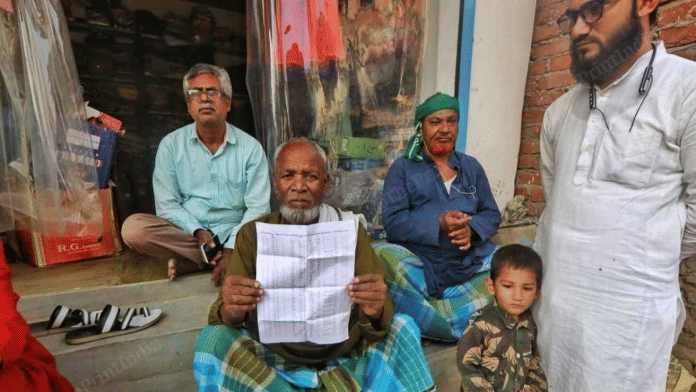

Alongside Qalam sits Farukh Lehar, who claims that his name has been struck off the voter list after the Election Commission conducted the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) in Bihar this year.

“I have my Aadhaar, PAN, ration card, everything, but I cannot vote this time,” he says, as he rushes to his house to bring a copy of the voter list compiled after the 2003 SIR in Bihar. “See, my name is second on the list here, but this time they have removed it.”

Across the village, several people claim that they were “harassed” tremendously by the administration trying to add their names to the voter list.

“My husband’s name was struck off. We spent over a thousand rupees, running to the office again and again to get it added,” says a woman in her 30s. “So, who else will we vote for when this is our condition? Of course, Tejashwi (Yadav of the RJD).”

Fears of the BJP exploiting a divided Muslim vote have created an unsaid consolidation of the community’s vote this time, says Qadri. “(Asaduddin) Owaisi is not a factor this time. The people are very vigilant now. They know the danger of disenfranchisement, deportations and demolitions is right at its door.”

Across villages, no conversation about Owaisi takes place without someone or the other expressing their suspicion of him being the BJP’s ‘B-team’.

The fact that even though Owaisi’s party, the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen’s (AIMIM), managed to win five seats in 2020, four of his MLAs defected to the RJD is repeatedly brought up.

“For us, there is nobody but Tejashwi, madam,” says the woman quoted above. “After he comes to power, we don’t know what he will do with us. But right now, he is our best bet,” she says, her voice carrying a blend of desperation and resignation felt by many in her community.

Madan, who draws the distinction between voting for survival and voting for expansion of political rights, agrees. “It is a battle to survive for the community right now. Development is not a priority.”

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: From pre-Emergency to post-Lalu era, the story of Congress’s irreversible decline in Bihar

Pls don’t rewrite history for convenience. Muslim League won more than 85% seats in Bihar in 1946 Provincial elections.

So, they were supportive of Muslim League and separate nation. Intact it is said that Pakistan was formed by Muslims of UP & Bihar.

Intact that is the reason why Urdu was declared official language of Pakistan. Urdu is otherwise not the language spoken in partitioned areas.

Don’t create facts out of thin air just to support your article.

Mr Shekhar Gupta, I am a fan of your journalism and is regular listener of Cut the Clutter. Don’t know how this article passed ‘The Print’ editing with fabricated facts.

Unless Muslims abandon their mentality of consolidation of votes and start thinking like an Indian, i.e. working for self and nation, they’ll suffer from backwardness. Soon even Tejaswi will abandon them.