Less than a week after the Lok Sabha results in which the BJP fell short of winning a majority, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat has said that a true ‘sevak’ must not be “arrogant”. He also said that the Opposition must not be treated like an adversary, and elections are not war.

At the same time, in an article published in RSS mouthpiece Organiser, Ratan Sharda, a lifetime leader of the Sangh, called the poll results a “reality check for overconfident” BJP leaders and workers, who did not hit the ground and did not listen to voices on the ground.

The statements have piqued curiosity amid widespread speculation that all is not well between the BJP and its ideological mentor. The speculations peaked in the middle of the Lok Sabha elections with BJP president J.P. Nadda saying that the BJP does not need the RSS to win elections.

ThePrint looks at the history of the BJP-Jana Sangh-RSS relations since the early 20th Century, and explains how the relationship has always been one fraught with tensions, internal power struggles, and compromises.

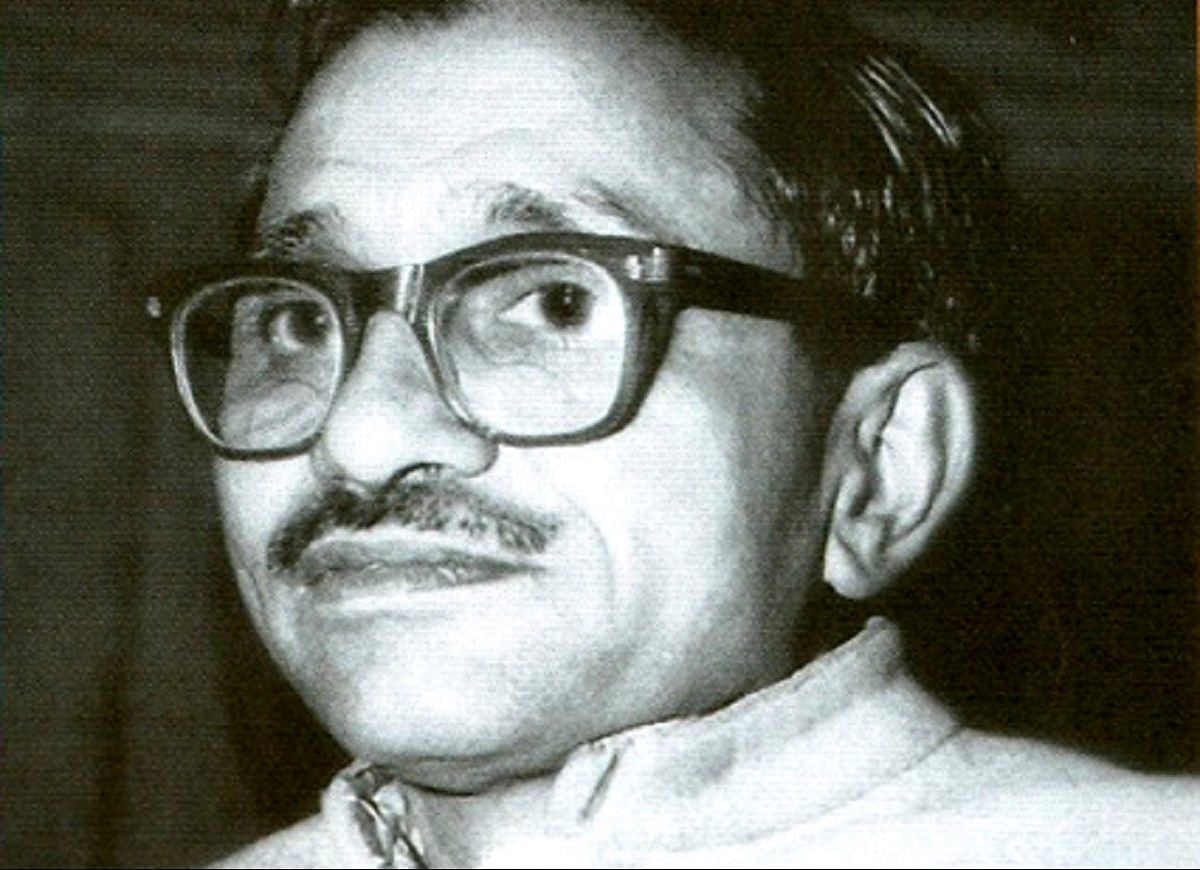

New Delhi: Karnataka pranth pracharak Mukund once wrote in a local newspaper about a conversation between Deendayal Upadhyay and a young swayamsevak. The swayamsevak, Mukund wrote, asked Upadhyay, “There is a saying that power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Will it not happen if the leaders of Jana Sangh get power?”

Unperturbed, Upadhyay, a pracharak of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and also the president of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the forerunner of the BJP, responded, “It is possible.”

“Then, what is the hope for the future?” the Swayamsevak asked.

“the power of Sangh,” Upadhyay replied. “If the political party started by the Sangh gets corrupt, the Sangh has the power to destroy it.”

That was the 1960s. The Bharatiya Jana Sangh had barely been around for a decade and had little electoral success till then. After the death of its founder-president, Shyama Prasad Mookerjee, less than two years after the party’s creation, the infant party was firmly under the grip of its ideological mentor, the RSS. At the time, the RSS could destroy the Jana Sangh had it so wished.

Over six decades later, at the end of what could be an unprecedented Lok Sabha election if the BJP comes to power for a third consecutive time — making Modi the only prime minister to have a third term after Nehru — the party president has suggested that it no longer needs the RSS to win elections.

In an interview with The Indian Express earlier this month, BJP president J.P. Nadda said, “Shuru mein hum aksham honge, thoda kam honge, RSS ki zaroorat padti thi… aaj hum badh gaye hain, saksham hain… toh BJP apne aap ko chalaati hai (We might have been less capable in the beginning, needed the RSS, but we have grown today and are capable. The BJP runs itself),” he said.

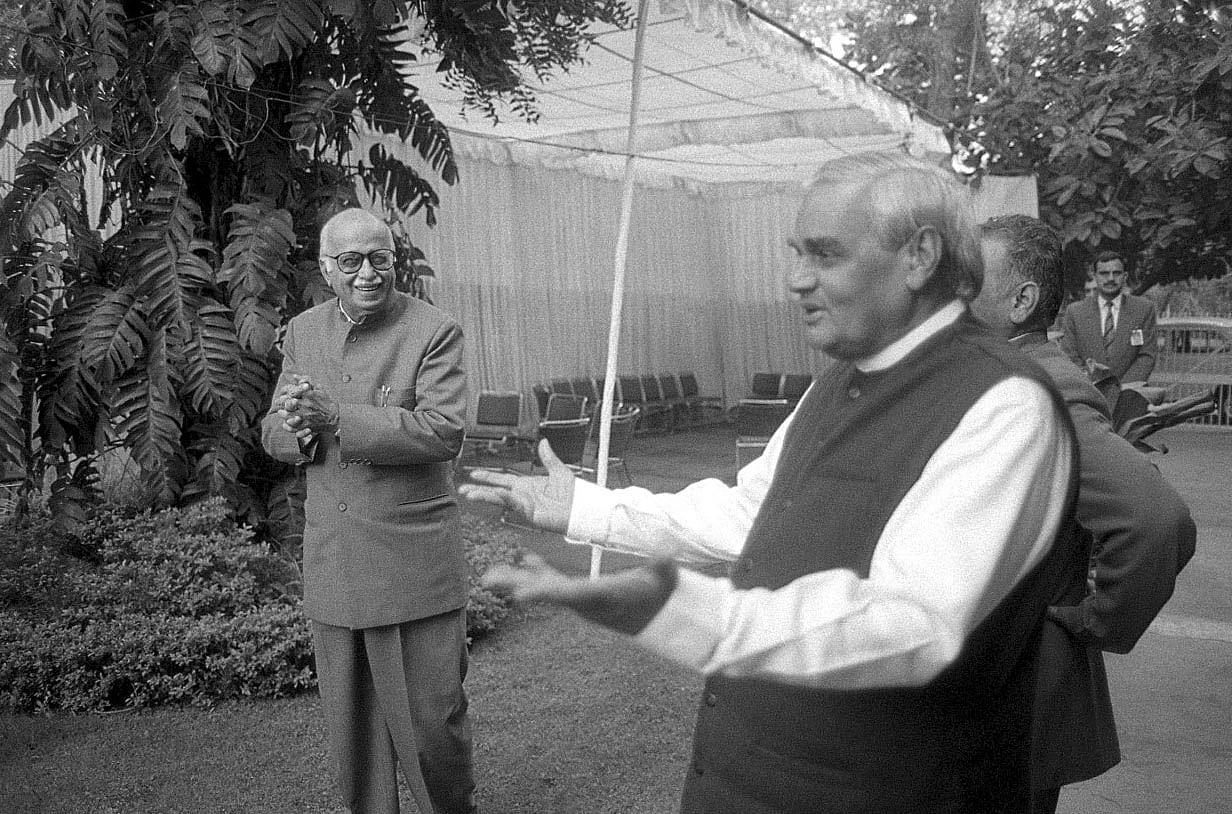

This is not the first time a BJP president has sought to assert the party’s independence from the RSS. In 2005, a year after the BJP got voted out of power, L.K. Advani, hitherto RSS’s best-known poster boy in the BJP, gave what’s remembered as a “landmark speech” in the history of the Sangh Parivar. While the BJP appreciates “continuing interaction” with the RSS, Advani said, its decisions must be independent.

On the face of it, the relationship between the BJP and the RSS is clear. The RSS is the ideological master. The BJP is only an instrument that the RSS needs to achieve what it believes is actual power — long-term cultural, ideological and psychological dominance.

In practice, however, fraught with power tussles, compromises, and ideological and tactical divergences, the relationship has often been messy.

As an RSS leader puts it, “In the long history of RSS-BJP relations, there has been 100 percent alignment between the two only once. It was when the BJP passed the resolution demanding the construction of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya in its national executive meeting held in (Himachal’s) Palampur in 1989.”

As the RSS completes 100 years in 2025 and the BJP 10 years in power under arguably its most charismatic pracharak-turned-prime minister, three questions are central to understanding their amorphous, complex relationship.

First, why did the RSS decide to function outside the political realm? Second, why did it then enter politics indirectly through, first, the Jana Sangh and then, the BJP? Finally, what do the several moments of friction between the BJP and the RSS tell us about the structural relationship the two share?

Also read: A swayamsevak Narendra Modi as PM—what complain could RSS have with BJP in power?

If not politics, then what?

The RSS was founded in 1925, 10 years after the founding of the Hindu Mahasabha, whose leaders immediately thought that in the RSS, they had found their youth wing. The Hindu Mahasabha would fight elections, and the RSS would supply the cadres. Even the British government thought so. In an intelligence report published in 1938, the government observed that the RSS was the “controlling influence” in the Hindu Mahasabha.

Except it wasn’t. The RSS did not plan to enter politics or play second fiddle to a political party. “Sangh is an organisation totally aloof from politics,” RSS founder K.B. Hedgewar said unequivocally. “Hence, it will work for no political party. A Sangh swayamsevak is at liberty to join any political party and work for it. He may participate actively in elections, too. But the organisation will not follow him. It will be aloof from parties and will not abandon this stand for any reason.”

The Hindu Mahasabha, which saw itself as the political voice of the Hindus, was aghast. “What will the Sangh even do if not participate in electoral politics?” the leaders of the Hindu Mahasabha wondered, disparagingly.

Chief among them was V.D. Savarkar, the party’s longtime president, who famously said, “The epitaph on a Sangh Swayamsevak will be: ‘He was born; he joined RSS; he died’.” Nathuram Godse, the future assassin of Gandhi, too left the RSS in 1932 over his disillusionment with Hedgewar’s apolitical stance.

The Hindu Sabha even tried to create an RSS-like organisation, the Ram Sena. Its volunteers wore khaki shorts and carried a spear with a Hindu Mahasabha flag attached to it. Later, once again, Savarkar created the Hindu Rashtra Dal, which emulated the RSS’s organisational structure.

The Sangh leadership, as Walter Anderson noted in his book The Brotherhood in Saffron, was considerably antagonised. But not enough to rethink their decision to stay out of electoral politics.

Under the second sarsanghchalak, Golwalkar, the RSS’s indifference to politics bordered on disdain. “A crow does not become the best bird in the world just because it happens to sit on top of the spire of a temple,” he once said, alluding to the aggrandisement of politicians.

“I do not think it was disdain. But, it was felt that the aims of the Sangh were unlikely to be met with electoral politics,” said Govindacharya, a long-time RSS ideologue. “Everyone used to wonder at the time, what does a Swayamsevak even do?” he said.

“Guru ji (Golwalkar) thought that there was a need to think about politics more deeply. If the British or the Muslims ruled India, one had to question the conditions that made this possible rather than simply replacing their rule with that of Indians,” he said. “Those conditions were collective apathy, lack of national consciousness and vitality that could not be attained with politics — they had to be cultivated assiduously day after day, generation after generation, in the shakha.”

The shakha, he said, was a model like no other — it was the means and the end.

Under Golwalkar, the network of shakhas began to grow rapidly in the 1940s, and the consensus to stay outside politics remained largely unquestioned.

But, with Gandhi’s assassination and the subsequent ban on the RSS in 1948, things changed. For sections in the Sangh, it was a wake-up call. Staying out of electoral politics was no longer sustainable.

“Thousands of RSS workers were thrown into jail, and nobody spoke a word in defence of the organisation,” said VHP president Alok Kumar. The voices within the Sangh which believed that the Sangh needed a political representative grew, and slowly, Golwalkar saw merit in that argument, he said.

It was a time when a former congressman and minister in the Nehru government, Syama Prasad Mookerjee, who had also been the president of the Hindu Mahasabha — he had resigned from the Nehru government in protest against the Nehru-Liaqat pact and from the Hindu Mahasabha, which he saw as communal — was looking for allies to float a political party.

He got in touch with Golwalkar, and the RSS was finally ready to take the plunge but not without a stern caveat. “Naturally, I had to warn him that the RSS could not be drawn into politics, that it could not play second fiddle to any political or other party since no organisation devoted to the wholesale regeneration of the real, i.e. cultural life, of the nation could ever function successfully if it tried to be used as a handmaid of political parties,” Golwalkar recalled as telling Mookerjee.

As BJP leader Swapan Dasgupta points out, “Golwalkar used to say that politics is like the toilet in the house. You don’t particularly like it, but you cannot avoid it either.”

As the disdain for politics gave way to pragmatism, it was decided that the RSS would lend some of its pracharaks — “staunch and tried workers, who could selflessly and unflinchingly shoulder the burden of founding the new party” as Golwalkar said — to the Jana Sangh. Deendayal Upadhyay, Balraj Madhok, Nanaji Deshmukh, and Sundar Singh Bhandari were among the first to go.

With the contours of participation clearly delineated, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh 21 October 1951 came into being.

But, just two years later, Mookerjee died. The Jana Sangh became leaderless. The RSS had to take charge.

Also read: ‘Heart has soured’—why UP’s RSS workers are lying low in BJP campaign

The first and the last tussle

In a bid to balance the RSS and non-RSS forces within the party, Mookerjee had appointed two general secretaries for the party when he was alive — Sangh pracharak Deendayal Upadhyay and a non-Sangh background politician Mauli Chandra Sharma, according to Anderson’s book.

On his death, however, a new equilibrium needed to be established. Sharma became the working president, but it was Upadhyay who had the sole executive authority over the party’s organisational structure. As argued by Anderson, “When the annual session met in January 1954, it was clear that the very energetic general secretary, who could rely on the support of the RSS cadre, had a firm control on the levers of power within the party.”

While the RSS grudgingly allowed Sharma to become president of the party, he was not allowed to have his way in organisational matters.

Alienated and isolated within the party over which he technically presided, Sharma asked for a democratisation of the party by eliminating the position of the organising secretary, the steel frame of the party, manned mostly by RSS pracharaks. The organising secretaries, as Anderson has pointed out, “supervised the day-to-day work of the local units; they were the major communications link between the different levels of the party; they played a major role in the choice of officers in the organisation and of candidates for party tickets; and they enforced compliance with executive decisions”.

It was this network of the organising secretaries which allowed the RSS to maintain complete control over Jana Sangh, and it was this system that forced Sharma to eventually resign as president. An RSS pracharak, S.A. Sohani, RSS sanghchalak of Berar, replaced him.

RSS mouthpiece Organiser noted in an editorial at the time that Sharma “suffered from a fatal flaw of an insufferable self-aggrandisement — even at the cost of the party. In this, he had no scruples as to the means he employed. Soon it became clear that he was hardly the man to lead a great and growing organisation.”

The power struggle had been resolved. The Jana Sangh had to be run the RSS way.

“The Jana Sangh became an extension of the RSS even though it was not planned,” said Dasgupta. “It had some autonomy, but it was completely guided by the Sangh.”

“This was the first and the last tussle of power between the RSS and non-RSS factions in the Jana Sangh or the BJP,” a senior RSS leader said on condition of anonymity. “After this, any tension that you see emerge between the RSS and the Jana Sangh or the BJP is essentially among RSS leaders themselves… There might be individual RSS pracharaks, who on going to the BJP, may have become too big or too ambitious, but they have all been RSS.”

Also read: Why RSS has recalled its man GV Rajesh from key organisational post in Karnataka BJP

RSS against RSS

When Upadhyay suddenly died in 1968, a new leadership crisis ensued within the party. The senior RSS pracharak Balraj Madhok, who as journalist Vinay Sitapti wrote in his book Jugalbandi: The BJP before Modi, had been important enough in the RSS “to be one of the gold coins loaned to Mookerjee to found the Jana Sangh”, was at the center of it.

While Madhok, as Sitapati wrote, hoped that he would be made president of the party after Upadhyay, it was Atal Bihari Vajpayee, younger to him, both in biological age and sangh aayu (the number of years an individual has spent in the RSS), who received the baton.

What followed were allegations of fratricide. Madhok, Sitapati wrote, alleged Upadhyay had not died in an accident but was murdered as part of a conspiracy hatched by Vajpayee and Balasaheb Deoras, a future sarsanghchalak.

At the same time, Madhok began to take an anti-RSS line in matters of the economy, pushing Jana Sangh to not just oppose Indira Gandhi’s populist overtures at the time, such as bank nationalisation, but also to merge with the Swatantra Party. His views remained unattended.

Increasingly alienated within the party, Madhok went to Golwalkar to complain about the women in Vajpayee’s life, Sitapati wrote. In 1973, when L.K. Advani became the president of the party, Madhok was expelled from the Jana Sangh.

This time, the RSS had backed Vajpayee, who, two decades later, would emerge as the first pracharak turned prime minister of India, albeit one with whom the RSS would go on to share the frostiest of relations when he would be in power.

Political recalibrations

“The 1977 elections after the Emergency was lifted was the only time in the history of Indian politics that the RSS participated in elections,” said Alok Kumar. “All the sangh workers were asked to campaign against the Congress, and for the victory of the Janta Party.”

But, once the Jana Sangh was merged with other parties, it was no longer considered kosher for the Jana Sangh camp within the Janata Party to continue seeking directions from the RSS. Much before the RSS and BJP relations were to be strained by coalition dharma, they came under the strain of merger dharma.

“Even after the Janata Party was in power, the Jana Sangh group kept taking part in samanway samiti meetings with the RSS,” said journalist and author Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay. “The issue of dual membership was raised, and the Jana Sangh group had to cut off its umbilical cord with the RSS.”

The RSS had to look beyond the Jana Sangh, he said.

In 1980, when the Janata Party government collapsed, and the party disintegrated, the Bharatiya Janata Party was formed under Vajpayee. But, the party was going to be no mirror image of the Jana Sangh. Stung by a dual membership controversy — Janata Party had banned its members from being ‘dual members’ of the party and the RSS — and still seeing themselves as the progeny of the idealistic and morally high-minded JP movement of the mid-seventies, the founders of the BJP decided to maintain its distance from the RSS.

“They did three things which underscored this distance,” said Mukhopadhyay. “One, they abandoned Deendayal Upadhyay’s Integral Humanism as the underlying philosophy of the party and adopted Gandhian socialism. Two, they did not resume the practice of ‘samanway samitis (harmonious meetings)’ with the RSS. And third, they stopped borrowing pracharaks from the RSS.”

The traditionalist faction within the party was seething with anger. Ahead of its first plenary session, Vijay Raje Scindia thundered that Gandhian socialism was adopted as the party’s guiding philosophy just to “appear progressive”. It would reduce the BJP to a “mere photocopy of the Congress”, she asserted.

Yet, torn between the desire to keep its original support base intact through ideological puritanism, and the need to attract a larger support base, the BJP decided to retain its new, moderate avatar.

But, the public consensus itself was shifting. The 1980s were a time of great political tumult in Indian history. There was separatism, militancy, and communal rioting across India. The time was ripe for religion-based political mobilisation.

In 1981, mass conversions of Dalits to Islam in Tamil Nadu’s Meenakshipuram came to the fore. In response, the VHP, which the RSS had begun to revive as the BJP grew distant from it, started the ‘ekatmata yagna (unification pilgrimage)’in 1983.

With the sole aim of “uniting the Hindus” as many as 92 religious caravans began to roll across the country from Haridwar, Nepal and the Northeast to the temple towns of Tamil Nadu and Gujarat. As an article in the India Today magazine noted at the time, the yatra was “the biggest show in recent times put up by Hindu revivalist organisations”, “literally putting on wheels the concept of Hindu solidarity”.

“The whole scene began to change politically. Even Indira Gandhi was taking a pro-Hindu line to develop a Hindu constituency,” said Mukhopadhyay. As the India Today article stated, while Indira did not publicly endorse the yagna, she did not oppose it either. The organisers interpreted her silence as ‘mounam sanmatilakshanam (silence is consent)’.

As Anderson stated, in the early 1980s, the RSS supported the Congress in some elections, created a new party called the Hindu Munnani in Tamil Nadu and increasingly mobilised the VHP to make up for its distance from the BJP.

Buoyed by the success of the ‘yagna’, the VHP readied its blueprint for the Ram Temple in 1984. It was to present it as a memorandum to Indira a day before she was assassinated. The elections were held, and the BJP headed by Vajpayee was reduced to two seats. A recalibration was once again necessitated.

In 1986, Advani took over as BJP president from Vajpayee. It was also the year when under pressure from the ulema, Rajiv Gandhi overturned the Supreme Court judgment which granted maintenance to Shah Bano, and subsequently, opened the locks of the Babri Masjid to ward off allegations of Muslim appeasement.

The BJP could no longer remain the dutiful heir to the JP movement. It had to go back to its roots. It turned to the RSS.

“Advani did away with Gandhian socialism and adopted integral humanism, started the ‘samanvay samiti’ meetings, and began to bring pracharaks into the BJP,” said Mukhopadhyay.

In 1989, the BJP formally passed the resolution demanding the Ayodhya Ram Temple. In the Lok Sabha elections that year, the BJP jumped from 2 to 85 seats. In the 1991 elections, it jumped to 120 seats, and in the 1996 elections, it jumped to 161 seats — becoming the single-largest party.

Vajpayee once again took over the presidentship of the party from Advani. The BJP was at its hitherto all-time high electorally, but the relations with the RSS began to rapidly deteriorate, and publicly so.

Also read: Ex-editor, jailed during Emergency — who is RSS No. 2 Dattatreya Hosabale, re-elected gen secy

BJP in power, RSS in opposition

In 1971, an article authored by “a Swayamsevak” appeared in an English daily. There were two roads ahead for the RSS and the Jana Sangh, it said. They could either choose to remain an ideological party and become a pressure group or compromise on ideology and come to power.

The article was written by Vajpayee.

It took him nearly three decades since then to come to power, but he did choose to compromise on ideology once he did. The RSS could not be unhappier.

“The first time the RSS actually flexed its muscle in government matters was in 1998 when in a midnight coup of sort, Sudarshan (the then sarsanghchalak of the RSS) scuttled the appointment of Jaswant Singh as Finance Minister in Vajpayee’s first Cabinet and got him to instead appoint Yashwant Sinha, who was seen to be closer to the Swadeshi Jagran Manch,” recalled a senior party leader.

This was just the beginning of almost a decade of simmering differences between the BJP and the RSS.

In 2000, Sudarshan launched a tirade against Vajpayee’s PMO. In a press briefing, he targeted BJP leaders Brajesh Mishra, N.K. Singh and Ranjan Bhattacharya, who the RSS considered as part of a “multinational lobby”.

The RSS became the most vocal opposition to the BJP government. As a 2005 piece in Frontline stated, it “got the VHP, and increasingly, the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS), to attack the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). While the BMS concentrated on its labour and privatisation policies, the VHP harped on the Ayodhya issue, chiding the Vajpayee government for doing nothing about it”.

While, in 2002, the RSS forced Vajpayee to make Advani the deputy prime minister hoping that the architect of the rath yatra would ensure that a Ram Temple is built in Ayodhya, Advani too chose “pragmatism” and “coalition dharma” over ideological fealty.

By the end of 2004, RSS cadres were left asking what being in power even gets them, said defence analyst and right-wing commentator Abhijit-Iyer Mitra. They completely turned their back on the BJP in the Lok Sabha elections. As mentioned in journalist Nalin Mehta’s book, The New BJP, the RSS-BJP worker ratio at the time was 1.5:1, Mitra said. “The BJP lost more than half of its organisational power in that election, and to everyone’s surprise, it was out of power.”

Mukhopadhyay agrees. In the 1984 election, when the BJP was reduced to two seats, the RSS had turned its back on it. In 2004, it did the same. In the 1980s, when the BJP strayed away from the RSS, the RSS turned to the VHP to implement its ideological agenda on the streets. In the early 2000s, it turned to the VHP, BMS, and Swadeshi Jagran Manch to attack the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance government.

“That was a time when we could not resolve differences as a family,” conceded Alok Kumar. “They spilled over. There was stress, yes, but the bond was not broken,” he said. “At the time, there were rumours that the RSS might start another party. Vajpayee ji responded to a question about these rumours by saying ‘If Sangh starts a new party, I will go to that party’.”

Yet, the relations between the BJP and the RSS, which had already hit the nadir, received yet another blow in 2005. In one of the most controversial television interviews in the Sangh’s history, Sudarshan asked Vajpayee and Advani to make way for the younger generation.

“Over the next few years, there was soul-searching and rethinking within the RSS too,” said Iyer-Mitra. “There was a strong section within the Sangh which felt that it had gone a bit too far… Both the RSS and the BJP learnt a lot from that episode.”

By the early 2010s, a new generation in the form of Modi was ready to replace the old guard. As several BJP leaders say privately, the RSS was not particularly keen on having Modi emerge as the prime ministerial candidate. But there were two important realisations. One, Modi was too popular even among the RSS’s karyakartas to be challenged, and two, the RSS did not want to repeat the mistakes of 2004.

As a BJP leader said on the condition of anonymity, “10 years out of power had taught the RSS that being in power makes it easier to live with compromises.”

Also read: The Republic is dead and no point blaming BJP-RSS. We need a new political language

The first ‘RSS government’

The ten years of the Modi government have been nothing like the six years of the Vajpayee government. As ThePrint editor-in-chief Shekhar Gupta wrote in 2014 — if Vajpayee was a mere ‘mukhauta (mask)’ of the BJP while the real face was entirely different, as Govindacharya once mockingly stated, in Modi’s case, the mask and the real face are exactly the same. He is, in effect, the first pracharak Prime Minister of India.

In his ten years in power, he has adequately demonstrated his ideological fealty to the organisation he comes from.

“The key difference is that Vajpayee and Advani were groomed in a Congress-dominated parliamentary setup… They were the products of the time of Congress hegemony,” said Abhishek Choudhary, author of the Vajpayee: The Ascent of Hindu Right (1924-1977). “Modi, on the other hand, has been groomed entirely in the RSS ethos and is a product of a time when the Congress hegemony was beginning to be challenged.”

Iyer-Mitra agrees: “Modi has no time for the so-called intellectuals, whose opinion Vajpayee and Advani did care about… He is, in that sense, 100 percent aligned with the RSS.”

“The influence of the RSS and its affiliate organisations in the government is enormous,” said Anderson. “If anyone sees the ‘samanvay baithaks’ organised by the RSS, all this analysis of the RSS losing its influence on the BJP will go away… Even Modi takes questions from the audience at these meetings,” he adds.

Yet, there are points of tactical friction even as there is strategic convergence.

“The BJP is bigger than the Sangh today,” a BJP leader, who requested anonymity, said. “There are moments when the BJP finds itself hamstrung by the RSS, especially the position of the sangathan mantris (a position held by Modi himself both in Gujarat and nationally), who want to exercise the same kind of influence over the BJP’s organisation as they did during the time of the Jana Sangh… That is obviously off-putting for the BJP whose own organizational prowess is par excellence now,” he said.

Moreover, no matter how much some sections of the RSS crib about a personality cult, they know that the RSS’s ideological project has gained enormously from Modi’s personality, he adds.

One recognises that in politics, one needs a ‘mahanayak‘, said Kumar. “We could not give the image of a superhero to Advani because he had always been in Vajpayee’s shadows.”

In that sense, Nadda could be right. Modi’s BJP may not need the RSS to win elections. But, whether that could be said about a post-Modi BJP or not remains to be seen. If the history of the two is anything to go by, the BJP may not be able to stray far from its ideological parent for too long.

This is an updated version of the story.

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also read: Hate in India has gone beyond control. Even Modi, RSS can’t stop it