If Germany had enjoyed the pre-war period with aplomb by making great strides into the Indian economy, garnering business of DM105 million in exports, now was the time to rethink its strategy. The Indian plight from which it had disengaged itself, being a votary of imperialism, suddenly began to haunt them. Educated Indians impressed them with their prowess and intelligence.

Indian oppression was beginning to look real and their fight for rights appeared just. There was a sea change in German attitude as the clouds of war began hovering over the horizon, making them see an enemy’s enemy as their friend. The Germans would eventually invest themselves in India’s independence struggle. Now that war was on the cards, it wanted to weaken the defence of the enemy at all costs, hoping to win or at least expecting a rapprochement from the enemy side.

Indian revolutionaries working in London, Paris and other European cities were being hounded by British authorities putting a check on their activities. They drifted towards Berlin, which by now was ready to welcome them. Help from Germany was initially sought by Bengali revolutionaries and groups such as the Dacca Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar, but the right time for this association coupled with German interest only arrived after the initiation of the First World War in July 1914.

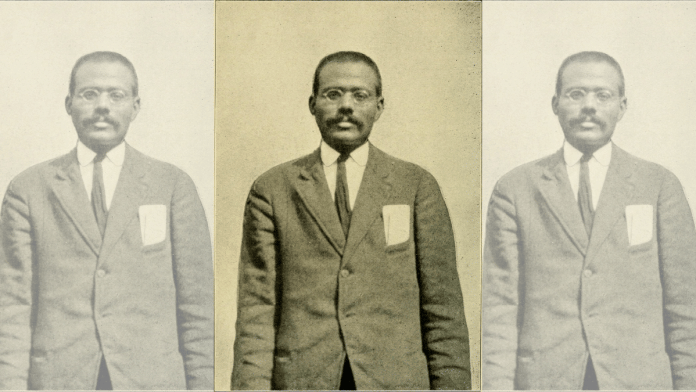

The Indian National Party, later known as the Berlin Indian Independence Committee, came into existence towards the end of 1914 with Virendranath Chattopadhyaya, who was studying in Germany in early 1914, as its architect. Virendranath Chattopadhyaya was closely involved with Shyamaji Krishnavarma’s India House earlier and was a close friend of Savarkar.

Also read: Gandhi wanted limits on media freedom. Not through law, but public opinion

The German foreign office started a search for Indian revolutionaries in Germany, Austro-Hungarian territories, Switzerland, America and the Ottoman Empire.

Shyamaji Krishnavarma, who was living in Geneva, expressed his reluctance to join this committee, citing old age. Madam Cama was confined in France. The most important revolutionary who lent support to the German ambition of invading India was Har Dayal, who arrived from Switzerland. Pingle, Barakatullah, Taraknath Das, Lahiri, Khankhoje and other Indian revolutionaries also arrived in Berlin to lend support.

The Germans and the Indians listed out a three-pronged strategy to strengthen the fight for Indian independence. The first part involved sending forces to Afghanistan and, with the help of the Emir, launching an attack on India.

The second part was to help the Indian cause with men, money and ammunition. A specific sum was pledged by German officials along with a promise to supply a cache of arms that was pledged for the Bengal revolutionary movement. Centres in Shanghai and Batavia would be set up to coordinate the arms operations as well as the dissemination of the news. Outside India, Siam (Thailand) was chosen to give military training by Germans to Indian revolutionaries.

Lastly, there would be the printing of propaganda literature and spreading it amongst the army, urging Indian army men not to fight the Germans. Spreading disaffection in the armies of France, provoking Indian pilgrims to Mecca, seeking the support of Indian students in foreign universities and bringing more revolutionaries to Berlin were other ideas that were put into action.

The Ghadarites under the leadership of Har Dayal had envisioned a twin strike on the British Army. The first through Afghanistan and the second through Kashmir where they believed that the distrust of the British was the highest amongst the local Muslim population, whom they believed would side with them when it came to a physical fight. Control over Kashmir was believed to be the first step towards gaining independence.

This excerpt from Rana Preet Gill’s ‘The Ghadar Movement: A Forgotten Struggle’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House.

This excerpt from Rana Preet Gill’s ‘The Ghadar Movement: A Forgotten Struggle’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House.