Onam is the most important festival celebrated by Keralites. So important that Mallu Twitterati make the #OnamSadya trend throughout the day.

This year, probably my first, I’m in Kerala for Onam, all geared up for a Diwali-type fervour. Diwali is, for Delhiites, the mother of all celebrations. It unfolds in two phases. First, the Diwali parties. These start a month in advance. If your calendar isn’t booked with Diwali invitations, you have lost out from the get-go. But that’s not enough. The type of party matters. If you are going mostly to your neighbour’s terrace for loud music, biryani, teen patti with a ten-rupee stake and a cold dinner at 2 a.m., it’s better to Netflix at home.

If, on the other hand, you are going to a house party with a Bali vibe, live music, tarot readings, eye candy, food stations supervised by celebrity chefs, card wagers starting at one lakh rupees a pop, you are getting there. This still doesn’t guarantee dinner before 2 a.m.

The second phase of Diwali is gifting. These can range from gadgets such as all things Apple to silver bowls, gold coins, hampers with wine, exotic snacks, dry fruit and all manner of goodies. If it is chocolates coming your way, then the pecking order is Alain Ducasse, La Maison du Chocolat and Pierre Marcolini, after which it dips to Sprungli and Godiva. By the time you get to Lindt, you are on a slippery slope and if it’s Ferrero Rocher in your hamper, you are in the gutter, but you console yourself by saying you are dealing witha cheapskate.

Last year, Fortnum & Mason’s tea became a popular gift. I wouldn’t have known this at all except for my incredible ability to eavesdrop. I was at the all-day diner of Oberoi for a business lunch. The only reason we chose this venue is that Oberoi has giant air purifiers and claim they have the cleanest air in Delhi. They even display the air quality on a giant monitor. That’s a big deal, especially in October, when the air is milky grey and acrid from the burning of crop stubble by our iron-lunged farmers in neighbouring Punjab and Haryana.

Also read: Mukesh Ambani’s succession plan for Reliance needs 3 ‘superstars’

I was sitting at lunch, at a table for two, next to the kitty-party ladies of Delhi. It was not always this way at Oberoi. It used to be the place for a quiet business meeting until the kitties invaded it. The chatter was unusually loud. They were discussing Diwali gifts and one of them said, ‘I’m getting Bloody Mary and Lemon Curd Tea from Fortnum & Mason, the London dukaan, for the Diwali hamper. You know, the one in the Nita video.’

Anyone who has been to Fortnum’s will know you don’t call it dukaan, or local store, under any circumstances. Fortnum’s is the super posh totty of department stores with two Royal warrants. You also don’t call Nita Ambani, wife of one of the world’s richest men, Nita. She’s not Nita to you, or anyone you know. In Mumbai, they respectfully call her Nita bhabhi, and the journalists truthfully call her the First Lady.

The reference to the tea was from a birthday video where the First Lady was wishing her daughter-in-law and talking about the girl’s love of food. The touristy tea from Fortnum made the list. It was evident that Kitty-party-lady had seen the clip, on loop. I’d seen it too, but not on loop. I had forwarded it to many people I know. It merited that.

‘This time we are not putting any drink-shink in the basket. It’s all different things coming from London, you know.’ This is how Diwali arrives in Delhi, on-trend and in the face, delivered by the kitty-party ladies.

You know Delhi’s Diwali celebration is over when you wake up the next morning and walk into a sulphur haze from the fireworks and order a nebulizer from the chemist in the next hour. But Diwali is months away, and I’m in Kerala, hoping to catch some excitement this Onam, even though I know the fear of catching Covid will dampen the celebration.

A fortnight before Onam, I’m starting to feel its Madrasi personality. The festivity starts only nine days in advance and Keralites spend hours each morning laying flowers in patterns on the porch or driveway, while brushing away drone-sized mosquitoes. This is how families, apartment blocks, temples, cities compete—with beautiful, elaborately designed flower murals that wilt by the next day, shrivelling in the heat, burying little flower worms under the weight of the elaborate design.

The Keralite runs around buying packets of kaya upperi and sharkara upperi, which is banana chips and banana chips coated in jaggery, to give to relatives and friends. If you are much loved you will get the set mundu or the two-piece garment that you wrap around like a saree in two parts, its little gold border making the pale-cream cotton glisten. The men will get a kasavu mundu made of the same fabric, which they wear by wrapping around their waist, sarong-like. Sometimes they will be gifted a shirt, but usually that’s because they’ve said they don’t want any more mundus. That’s your gifting done.

Mothers, mine at least, spend endless hours in the kitchen making bits that go with the Onam sadya or feast. Puli inji, a tamarind and ginger preserve, vadukapuli achar, or lime pickle, and so on—filling the kitchen with sweet and sour smells and dirty dishes that need doing.

Younger women do the kaikottikali, a slow dance in circles, as though they are in no hurry for the festival to either begin or end. Men gather other men and then some and head to the backwaters to watch yet another bunch of men race each other in long black wooden snake boats called chundan vallam. The boats, sometimes 120 feet long, rise nearly 20 feet high near the prow, like a cobra with a raised hood.

They are handcrafted and each boat represents one village in the race. The race called vallamkali is held in Kerala’s backwaters. They’ve been racing this way for four centuries. The rowers trained, shortlisted and carefully selected for the race must stay celibate in the run-up to the race. A race in which testosterone is the only display. I’m sure it’s all designed that way—the race, a release for their pent-up energies. Women also drop by to cheer the men and ogle at the chiselled bodies of the rowers, all attained on a high-carb diet of mountains of rice.

After the excitement of the race dissipates, everyone goes to sleep by 10 p.m., some more drunk than others. On sadya day, the main day of celebration, a grand vegetarian feast is beautifully laid out on banana leaves. Once the sadya is over, which is by noon, you roll over and have an early afternoon nap because you can barely move.

On the fourth day of Onam, grown men with potbellies get tiger faces painted on them to enact puli kali, or the dance of tigers. It’s very much a Thrissur thing. They gather on the Round from various villages and put on a show The body painting is an elaborate process that takes several hours, and when it’s done, tiger eyes glowing like embers, set into men’s breasts, sit above rapacious tiger mouths on their bellies—their real expressions hidden behind a second tiger mask they wear. The tiger’s expression on quivering bellies sometimes mirrors the mood of the artist.

Some look like a lovable Disney cartoon, their fierceness eroded by the paintbrush. Young boys also take part, but they don’t fit in among men, intoxicated, dancing through the streets. And then Onam is over—just like that, tame, a bit soft on the edges. But I get to spend Onam with my parents, and for that I’m glad.

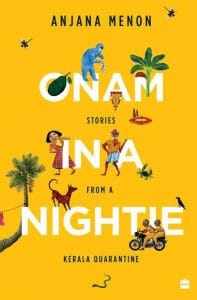

This excerpt from Onam in a Nightie by Anjana Menon has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from Onam in a Nightie by Anjana Menon has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.