I know what some readers might be thinking: How can you be Queer and Muslim? Aren’t the two exclusive? Well, first of all, the very existence of the range of Queer Muslims here speaking proves the lie. But let’s delve under the surface: it is hard to say what a ‘Muslim’ is. There are, of course, a multiplicity of Islams, a range of perspectives and schools of thought about the way to practice, what the religion means and how to access the divine.

This plurality is historical: Nearly immediately upon its founding, there were already multiple streams of Islams, lineages that continued, in the first generation of Islam’s founding, to diverge. As Islam spread, within the two centuries following the Prophet’s death, across the Maghreb to the west and then into Spain and France to the north and into the rest of Africa to the south, and along the Silk Roads into China to the east, and on into South Asia and Oceania, and eventually to the Americas via the slave trade, it continued to develop, change and grow, and to influence and be influenced by the cultures it encountered.

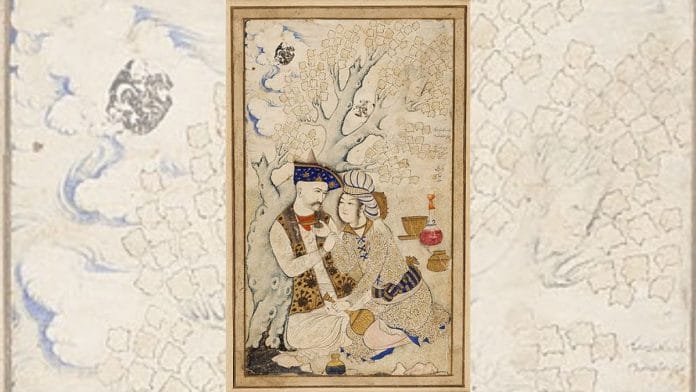

Islam as it’s practiced in the Middle East bears only some similarities to the culturally distinct South Asian Islam and so on. This flowering found what many scholars consider to be its first ‘Golden Age’ in the medieval Arab Mediterranean, including the Levant, Italy, North Africa and, particularly, in the Western Caliphate whose capital was in Al-Andalus in the southern Iberian Peninsula. It was there in cities such as Granada, Toledo, Seville and Córdoba that Muslim scholars, artists and artisans were pioneering astronomy, chemistry, mathematics, architecture, garden design, poetry, bookmaking and illumination, the study of languages and translation, physics, engineering, music and dance.

Also read: There’s no concept of despair in classical Indian philosophy and art

My point is that that plurality in Islam and acceptance of Muslims of alternative sexualities and genders are neither modern, postmodern or contemporary—or if it is ‘modern’, it is modern in the sense that Syrian poet Adonis used the term: that modernity came to the Arab world in the seventh century with the spread of Islam across the region and the conversion of the political institutions of the day. This plurality has been part and parcel of Islam since nearly the moment of its founding.

One significant verse of the Quran appears near its beginning: ‘This is the book. In it there is no doubt.’ Growing up under the shadow of such an authoritarian dictum, I continually wondered at my own doubts, engagements with faith, forays away, through and within dogmatic teachings. Only recently, in a new translation by Muhammad Sarwar, I read a different rendering of the same verse: ‘There is no doubt this book is a guide for the pious.’ It’s not just the wording but also the punctuation (in fact, Sarwar’s is closer to the original Arabic), which opens the meaning up. There is space in the book—for engagement, for conversation, for interpretation.

My father told me once about the story of ‘one hundred and four’ books revealed by God to prophets through the ages to all the various peoples of the world. For each people, throughout time, there was a different revelation, in a form that they would be able to hear and understand. Four of these books are mentioned by name in the Quran—the Taurat, the Quran itself, the Injeel of Isa (considered to be a lost text) and the Zubuur—the Psalms of David—but a Muslim would believe there are a hundred others out there whose names we do not know—that perhaps the Bhagavad Gita is one, or the Heart Sutra, or the Yoga Sutras, or the Popol Vuh, who can say?

The hundred books of course call to mind the ‘hundred names of God’, of which ninety-nine are named in tradition, the last one being secret. Always this dark place, the place of the unknown, the place you cannot go. A place where you are not sure what is what.

This sense of unsurety is even built into the very way we celebrate the revelation of this Quran. During the month of fasting—Ramadhan—we celebrate Lail-at-al-Qadr, the Night of Majesty, on which the scripture was said to be first revealed. But scholars do not agree on the actual historical date, saying only it is an odd-numbered evening in the last third of the month. So, traditionally, we celebrate the occasion on three separate evenings—the nineteenth, twenty-first and twenty-third evenings. It sounds manic and amazing and it is. It’s a miracle of unknowing and allowing the mystery of that to subsume the centralization or systemizing of a single day.

Perhaps, it remains the province of literature and the creative arts to privilege doubt itself, to create structures for meaning, to privilege and plumb the notions of bewilderment, doubt and interrogative spirituality. Though Islam requires five daily prayers and an obligatory pilgrimage, the Prophet also said, ‘One hour of work towards attaining knowledge is worth sixty years of worship.’

And what is that worship towards? The five daily prayers are performed in the direction of the qibla—the direction towards the Mecca Masjid, more specifically to the Kaaba, a black square structure at its heart. The famous hajj, obligatory on every adult Muslim, takes one to this same building, called colloquially the House of God. The house itself—like every mosque—is empty inside.

Perhaps it is only the Queer person—perennially and by definition outside the mainstream of culture, politics and organized religion—who can know God. Perhaps it is only the one who has turned their back on what they had been taught to be true and tried instead to really live and learn by their own experiences in the world who can attain knowledge and enlightenment. All the prophets of old, after all, had to abandon their upbringing and own religions to find what was known: Abraham came to Arabia, Moses turned his back on his adoptive father, Joseph too, Jesus disappeared into the desert, the Prophet Muhammad went up into the mountains, where a spider spun a web across the mouth of the cave in which he hid.

Maybe the truth is that it is the rebel, the outsider, the exiled, who can shine most brightly in the night, lighting the path for the rest of us to find our way.

This excerpt from Kazim Ali’s ‘On the Brink of Belief’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from Kazim Ali’s ‘On the Brink of Belief’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.