In India today, yoga and kama are not mentioned in the same breath, because the former is thought to be about spirituality and asceticism and the latter about psychological and physical pleasure, and never the twain shall meet. This false dichotomy is the unfortunate result of a twisted Indian modernity which has internalized— and indeed, made holy—the terrible Victorian prudery that was imposed in the colonial era on the remarkably liberal and life-affirming ideas of Hinduism. Ideas that were also at the heart of Bhakti and Sufi mysticism, in which the yearning for union with God is expressed in the language of pure eroticism.

Lord Șhiva is Aadi Purusha—Ishwara, the Supreme Consciousness—before he is Aadi Yogi, or indeed any of his various forms. And as Aadi Purusha—or just Purusha—he describes 112 ways to enter into the ultimate, transcendental state of consciousness. These include breath awareness and control, concentration on various centres (chakras) in the body, non-dual awareness, chanting the primal sound, training of the body in balance and mindfulness through intricate postures, and contemplation through each of the senses. Shiva is believed to have taught Parvati, his first and ideal student, all of this through 84 asanas of yoga (of which only a very few could be apprehended by mortals, and just about five are described

in the classical texts). But if Shiva is Purusha, the embodiment of supreme consciousness, Parvati is not merely his student; she is Aadi Shakti, or Prakriti, the embodiment of supreme knowledge—which is consciousness in action. Without her, there would be no creation. All that exists in the universe—in fact, the universe itself—results from the union of Purusha and Prakriti. In other words, it results from from kama. And kama began with yoga.

Yoga, which is equally about the mind, the body and the soul, is the science of ultimate balance—between dharma (duty, or ‘right living’), artha (economic well-being), kama (erotic desire) and moksha (enlightenment or liberation), which are the four goals of life in classical Hinduism. Sexual satisfaction is thus essential for a full and healthy experience of life. The most visible manifestations of yoga are physical poses or asanas and these were the easiest to depict. Hence the profusion in India’s pre-modern sculpture and art of

people engaged in a variety of sexual acts, the positions inspired directly by yoga asanas.

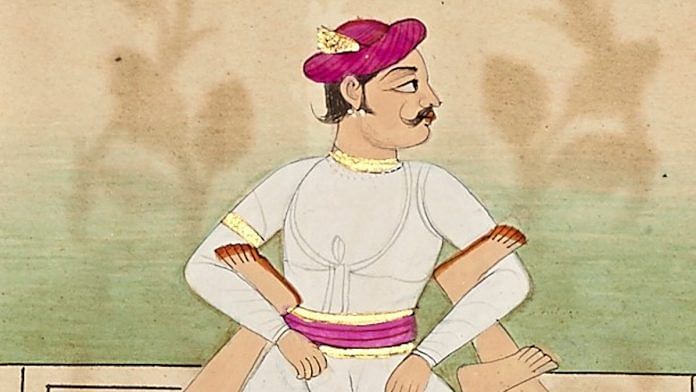

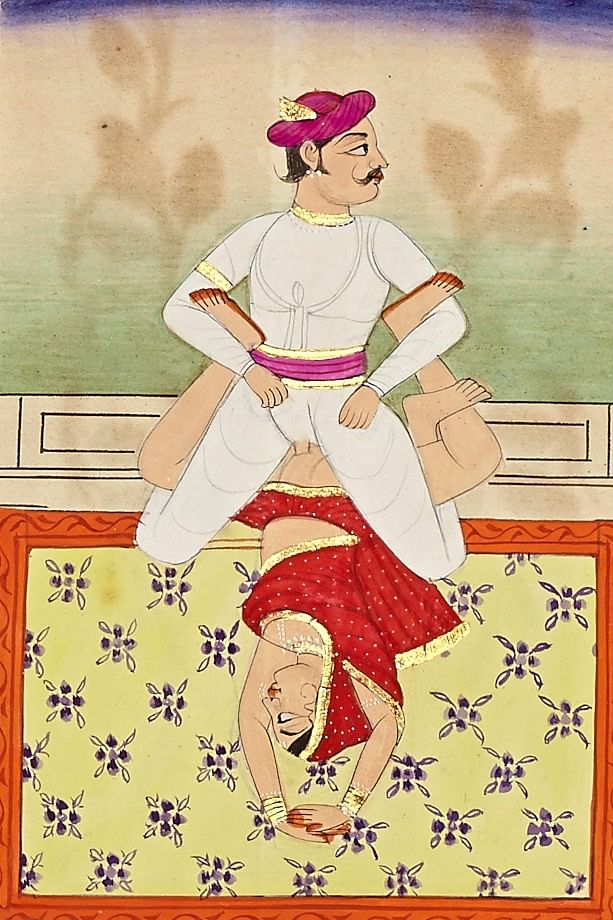

Sometimes, especially in miniatures produced from the 16th or 17th century CE

onwards, these positions seem utterly improbable and beyond the capacity of any

human being. These over-the-top acrobatics are not to be taken literally; they are

about uninhibited play and delight. But their root also lies in the same philosophy of

celebration and a balanced, pragmatic life that is the essence of yoga.

Also Read: ‘Unpleasant eyesores’ – Sleek and modern Bangalore is ashamed of its sex workers

Scholars and aesthetes have offered other explanations for the fevered, exaggerated and improbable love-making that is seen on the outer walls of many Hindu temples and in folk paintings and artefacts which were sold near temples (in some places they still are—the pattachitra scrolls in Puri, for instance). One theory is that all the images of sexual excess overwhelm and then cleanse the senses as we approach the inner shrine and the sanctum sanctorum; our minds and hearts are sated and purged of desire, and thus fertile soil for divine grace.

Another theory, which would apply more to miniatures and similar erotic art, is that

the fevered

sexuality might have been caused by the strain on sexual freedom in medieval

India—thus, sex, condemned in real life, came to be celebrated wildly in art.

Either way—disciplined and intricate yogic poses, or eye-popping contortions and

acrobatics—the aim is to wholeheartedly accept a great gift of life and immerse one’s

senses in erotic bliss. Just as one must also immerse oneself in worldly knowledge

at the appropriate time, and then in spiritual and transcendental knowledge.

Both kama and yoga are central to the Kamasutra, the mother of all the kama

shastras (erotic texts) of India. The Western world, and even many Indians—including those who are ashamed of our traditions of erotica and also those who are not—view the Kamasutra as only a book about sexual gymnastics, aphrodisiacs, love bites and so on. It is in fact a remarkable guide to pleasurable living, aesthetics, grooming, patience in indulgence, and sexual etiquette.

Also Read: Even thinking of Menopause made 40-year-old Mona fall apart—until she found Dr Rosy

One of the first Indian sages to reflect on kama was Shvetaketu, son of Uddalaka, who recorded a summary of the sacred bull Nandi’s descriptions of Shiva and Parvati’s coupling. Nandi, Shiva’s vahana (vehicle) and doorkeeper, is believed to have witnessed the epic love rituals of his master and mistress and in stunned enlightenment, he later whispered them to Shvetaketu. Over centuries, other sages—Swayambhu, Manu, Brihaspati and others— interpreted and expanded Nandi’s and Shvetaketu’s revelations. Until finally, sometime in the 3rd century CE, a celibate yogi, Vatsyayana, refined and collated all their work to produce the Kamasutra. There are also versions of this myth which say that Nandi revealed the secrets of divine love-making directly to Vatsyayana.

The Kamasutra became the iconic book for a pleasurable life to be led by men and

women. In premodern India, the study of the erotic was an extremely significant and

substantial part of Indian philosophy and literature. Vatsyayana’s masterpiece inspired several Sanskrit scholars, poets and writers who established a distinct genre of writing which came to be known as the Kama shastra.

The Kamasutra was also a defining influence on premodern sculpture and art. And in the evolved spirit of living that came from liberal Hinduism, the Kamasutra and other kama shastras inspired art in the service of the divine. We see this in the exquisite erotic sculptures on the walls of the temples in Khajuraho, Konarak, Hampi and Modhera, among other sites, where men and women are shown in states of mithuna (intimacy) and maithuna (sexual acts). In the advait or non-dual philosophy of Hinduism, this is the union of atma (soul) with paramatma (God) expressed in the metaphor of sexual union. Therefore, nothing is prohibited, nothing is sullied by shame, and we see remarkable depictions of frankly sexual yogic poses and acrobatics.

Devangana Desai writes in her book Erotic Sculpture of India: ‘In sculptural art, there

are some postures which do involve Hatha Yoga techniques. These are seen in the head down poses of Khajuraho, Padhavli, Belur…Hatha yogic techniques can also be seen in some of the intricate sitting and sleeping poses of Bhubaneswar, Lingaraja and Konarak.’ Alex Comfort, writing on India’s kama shastras, observes: ‘One complete sequence of bandhas from Vatsyayana on appears to derive directly from yogic exercises, and this sequence becomes longer and more complicated in the latter erotic treaties, until it includes really exorbitant tours de force, such as coition with the woman head down in sirshasana.’

Evidence of ‘sexo-yogic’ positions is also found in Tantric Buddhist traditions. One such is Tantric Sadhana for the immobilization of the three jewels, i.e., thought, breath and semen. The Yab-Yum image of Tantric Buddhism is symbolic of delayed ejaculation or coitus reservatus for the purpose of heightened consciousness.

The interesting point to note is that it is usually the women—slim, svelte and

athletic—and not the men, who are shown in intricate yogic asanas. Probably they

were the facilitators for kayasadhana (body discipline). Or they were courtesans

whom male patrons turned to for help when their libido was flagging.

This excerpt is from ‘Yoga and Kama; The Acrobatics of Love’ by Alka Pande has been published with permission from Speaking Tiger

This excerpt is from ‘Yoga and Kama; The Acrobatics of Love’ by Alka Pande has been published with permission from Speaking Tiger