Today there is neither agreement that the [colonial] empire produced hell nor agreement that protestations of good intentions are an inadequate excuse. Countless anticolonial thinkers and historians have proven the British Empire’s morally bankrupt foundation in racism, violence, extraction, expropriation, and exploitation. India’s anticolonial leader Mo- handas Gandhi adopted a nonviolent protest strategy as the empire’s opposite: “Let it be remembered,” he wrote in 1921, “that violence is the keystone of the Government edifice.” But the hold of this much-documented ugly reality remains slippery. According to a 2016 study, 43 percent of Britons believe the empire was a good thing, and 44 percent consider Britain’s colonial past a source of pride. A 2020 study showed that Britons are more likely than people in France, Germany, Japan, and other former colonial powers to say they would like their country to still have an empire.

As Britain prepares for a new role in the international order after Brexit, a report on “Renewing UK Intervention Policy” commissioned by the Ministry of Defence explicitly invokes a nostalgic view of the empire to revive the case for intervention: “Because of its imperial past, Britain retains a tradition of global responsibility and the capability of projecting military power overseas.” Britons celebrate the virtuous heroism of the abolition movement that ended British participation in the slave trade in 1807, but often at the expense of remembering Britain’s central role in the slave trade until that point and the many forms of bonded labor it exploited thereafter. The record of British humanitarianism submerges the record of British inhumanity.

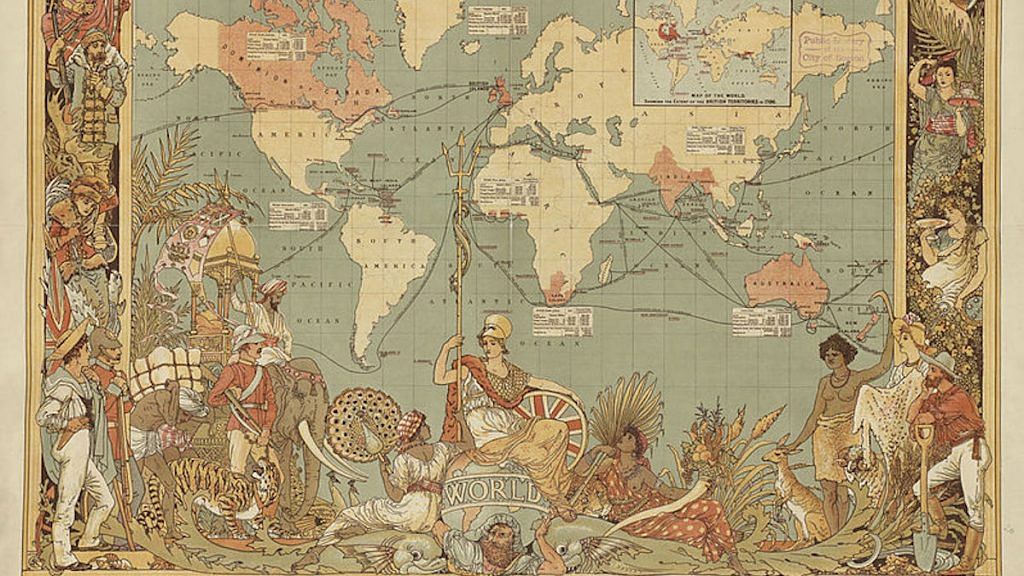

In public memory, redemptive myths about colonial upliftment persistently mask the empire’s abysmal history of looting and pillage, policy-driven famines, brutal crushing of rebellion, torture, concentration camps, aerial policing, and everyday racism and humiliation. Balance sheets attempt to show that the “pros”—trains, dams, the rule of law—outweighed the “cons”—occasional violent excesses, racism—despite the ambiguous impact of many alleged “pros” and the deeply flawed premise that we can judge an inherently illegitimate and immoral system by anything other than that illegitimacy and immorality. The end of empire, especially, is extolled as a peaceful, voluntary, and gentlemanly transfer of power. The former Labour prime minister Clement Atlee proclaimed in 1960, “There is only one empire where, without external pressure or weariness at the burden of ruling, the ruling people has voluntarily surrendered its hegemony over subject peoples and has given them their freedom.” In fact, decolonization of India, Kenya, Malaysia, Cyprus, Egypt, Palestine, and many other colonies entailed horrendous violence—none of which has been formally memorialized or regretted, unlike other modern crimes against humanity, such as the Holocaust and Hiroshima.

Also read: When India sent scores of prisoners to Iraq as sweepers during World War I

We have not arrived at this forgetting and the easy postimperial conscience it enables by accident. Public memory about the British Empire is hostage to myth partly because historians have not been able to explain how to hold well-meaning Britons involved in its construction accountable. But how can we rightfully gainsay the protests of earnest people confident in their moral soundness and in their incapacity for unjust behavior? “Hypocrisy” helps describe but does not help explain such human folly. No one thinks they are a hypocrite. And historical analysis framed as the unmasking of hypocrisy acquires a prosecutorial tone that vitiates understanding. Not all rationalizations are cynical and transparent. We have to take the ethical claims of historical actors seriously to understand how ordinary people acting in particular institutional and cultural frameworks can, despite good intentions, author appalling chapters of human history. The mystery here is genuine: How did Britons understand and manage the ethical dilemmas posed by imperialism? To be sure, there is a story about the “banality of evil” to be told—about the automatic, conformist ways in which ordinary people become complicit in inhumanity. But in the case of the British Empire, the bigger story is perhaps that of inhumanity perpetrated by individuals deeply concerned with their consciences, indeed actively interrogating their consciences. How did such avowedly “good” people live with doing bad things? If we can answer this question, we will be able to solve much of the mystery about the lack of bad conscience about empire among Britons today.

The quip most frequently invoked to depict the empire in charmingly forgiving terms is the Victorian historian J. R. Seeley’s line that the British acquired it in “a fit of absence of mind,” that they were reluctant imperialists saddled, providentially, with the burden of global rule. But it was not through absence of mind so much as absence, or management, of conscience that Britain acquired and held its empire. What we call “good intentions” were often instances of conscience management—a kind of denial— necessary to the expansion of imperialism and industrial capitalism in the modern age. The focus on intentions presumes active, unmediated conscience. We might instead ask how conscience was managed, what enabled individuals engaged in such crimes to believe and claim that they were enacting good intentions. Britons did this in a manner that has made historical reckoning with imperialism more complicated than reckoning with, say, the obviously monstrous aims of Nazism. This is ironic given a long-standing diplomatic discourse about “Perfidious Albion”—the idea that the British are natively dishonorable, prone to betray promises (i.e. good intentions). But it was partly the burden of this stereotype that provoked loud protestations of good intentions, which many now credit more than the evidence of their destructive impact. The claim of “good intentions” that enabled the violent effects of empire cannot be invoked to re- deem them. It would be akin to arguing that greater discretion about their murderous intentions would have somewhat redeemed the Nazis. Nazi objectives were openly murderous—the “cleansing” of Europe—but the ideology of liberal empire required respectable cover, and lasted longer because of it. The real value of claims of good intentions lies in what they reveal about how Britons managed their own conscience about the iniquities of empire.

Historians will continue to expose the hypocrisies of imperialism, but here I want to show how certain intellectual resources, especially a certain kind of historical sensibility, allowed and continue to allow many people to avoid perceiving their ethically inconsistent actions—their hypocrisy— in the modern period. Culture, in the form of particular imaginaries of time and change, shaped the practical unfolding of empire. This is a book about how the historical discipline helped make empire—by making it ethically thinkable—and how empire made and remade the historical discipline. We are looking at how the culture around narrating history shaped the way people participated in the making of history—that area of rich overlap created by the two meanings of “history”: what happened, and the narrative of what happened. Essentializing representations of other places and peoples laid the cultural foundation of empire, but historical thinking empowered Britons to act on them. The cultural hold of a certain understanding of history and historical agency was not innocent but designedly complicit in the making of empire.

Also read: That Muslims enslaved Hindus for last 1000 yrs is historically unacceptable: Romila Thapar

I offer this narrative, not as an attack on the historical discipline (whose tools are what allow me to write this book), but to recall how it has figured in the making of our world and how the world it made changed it over time, and to defend its relevance to making new history in the present. Many scholars have tussled over the positive and negative impacts of Enlightenment values and the provincial and universal origins of those values. I want to look under the hood and see how certain notions of history nurtured during the Enlightenment “worked” in the real world and how successive generations have adapted those notions to the moral demands of their time.

In key moments in the history of the British Empire covered in this book, Britons involved in the empire appeased and warded off guilty conscience by recourse to certain notions of history, especially those that spotlighted great men helpless before the will of “Providence.” This was not some amoral notion about the ends justifying the means. Machiavellianism is about political gain as its own end, without scruple. My protagonists were deeply concerned with ethical judgment but believed it was impossible without sufficient passage of time. Their understanding of conscience was grounded in different ways in notions of historical change. In the modern era, competing ideas about how such change happens shaped understandings of human agency and thus personal responsibility—the capacity, and thus complicity, of humans in shaping their world.

Much of the “modernity” of the modern period lies in a new self-consciousness about conscience. I don’t mean to imply a secularization of thinking about conscience; in some instances, the historical sensibility informed, supplemented, complemented, or was grafted on to religiously based notions of conscience. (Nor is this a book about dissent or state protection of conscience.) The point is that people were thinking about and managing conscience by reference to proliferating discourses about human history—about how and why history evolves.

For instance, liberal theories of history envisioned “progress” brought about by the will, usually, of great men (chosen and guided by Providence). Marxist theories instead attributed heroic agency to the proletariat (and, to be fair, the bourgeoisie). Both were imbued with certain presumptions about race and economic progress. Such theories of history, carried around in a nineteenth-century Briton’s mind, were motivating—galvanizing the exercise of agency—and exonerating insofar as they invoked higher ultimate ends or “context”—the way circumstances or the needs of history constrained agency and thus personal responsibility. My interest is in the cultural force of such notions; the neurological and philosophical understanding of intention and agency comprise a vast terrain of knowledge beyond this scope.

Also read: In European history, the World Wars are seen as monstrous aberrations. They were not

Of course, people also adapt their sense of history to the needs of conscience: an eighteenth-century plantation owner in Barbados might self-servingly celebrate his personal, entrepreneurial agency in transforming his land into an economic powerhouse, giving short shrift to the government policies and inherited wealth that in fact enabled his success. Fast- forward to 1836, after the end of slavery, and we might find his son equally self-servingly downplaying his personal capacity to ensure his continued prosperity without governmental reparations for his loss of property in slaves. The notion that change depended only on individual entrepreneurial prowess was now inconvenient. The vice of historical change in which he was caught did not stem his greed but did broaden his historical imagination so that he could perceive the role of circumstances more than his father could.

I began to perceive the link between conscience management and the historical imagination with a sudden epiphany about the protagonist of my previous book, Empire of Guns: The Violent Making of the Industrial Revolution (2018). The most important eighteenth-century British gun- maker was Samuel Galton. He was a Quaker, perhaps the group most associated with questions of conscience in modern Britain. As I recounted in that book, he defended his business to his fellow Quakers in 1796 by arguing that there was nothing he could do in his time and place that would not in some way be related to war—that was the nature of the British economy at the time. I used this insight to assemble a new narrative of the industrial revolution: Galton was telling us that war drove industrial activity in the West Midlands in his time. But was it true that he actually could do nothing else? On later reflection, I realized that his thinking revealed the power of historical arguments in assuaging his conscience. He believed that he could do nothing else, given “the situation in which Providence” had placed him. A historically determined reality, in his mind, constrained his desire to fulfill his promises as a Quaker. As it turns out, his logic echoed emerging Enlightenment understandings of history as a system of ethical thought; Galton’s obligations as a Quaker forced him to reveal the workings of cultural notions that were increasingly pervasive. Indeed, they likely underwrote the Quaker sect’s own quiet acceptance of his family’s business for nearly a century until that point. So began my thinking about this book.