Gandhi made his own position on the Poona Pact of 1932 quite confusing. On the one hand, he had claimed that though he was a Touchable by birth, he was an ‘Untouchable by choice’, who represented ‘the lowest strata of the Untouchables’ (Pyarelal 1932: 20). In his conversation with Ambedkar on 22 September, Gandhi had even claimed that because he was an ‘Untouchable by adoption’, he was ‘more of an Untouchable in mind’ than Ambedkar (60). But in the course of that very conversation, Gandhi referred to the Untouchables as ‘your community’, and made a strong plea to Ambedkar on behalf of ‘my Caste Hindu brethren’ (70).

Gandhi’s dual position was also evident in relation to the term he had started using, ‘Harijans’ or ‘people of God’. Writing in Navajivan on 3 August 1931, he said he had chosen the term, suggested by one Jagannath Desai from Rajkot, as it was a ‘beautiful’ alternative to ‘Antyaja’, and had been coined by a Brahmin saint, Narasinh Mehta, ‘the father of Gujarati poetry’ (CWMG 47: 244–45, 248). Gandhi had not consulted any Untouchable organisation before thrusting a name on them, and he saw nothing amiss in his action. Presumably, he saw himself as one of the ‘Harijans’. But after the Poona Pact, he distanced himself from them by telling them that they could hold his life as ‘hostage’ for the fulfilment of the spirit of the Pact (CWMG 51: 145).

Gandhi thus flitted between positions in his professed relation with the Untouchables. In 1932, Ambedkar did not recognise this shifting position and its implications. He felt Gandhi had merged with the DCs. Apart from whatever Gandhi had told him during their meetings in Yerawada Jail, what drove Ambedkar to that conclusion were some statements on untouchability issued by Gandhi from the prison in early November 1932.

In the first statement, issued on 4 November (CWMG 51: 343–45), Gandhi said that he found ‘no warrant for untouchability’ in the Gita, which was a ‘book of life’ that was ‘quite enough’ for anyone to understand ‘what Hinduism is and how one can live up to it’. Earlier in the statement, contradicting the views he had expressed in the 1920s, Gandhi said that restrictions on inter-caste dining and marriage were ‘no part of Hindu religion’. In the second statement, issued on 5 November (CWMG 51: 347–48), Gandhi described the condition of the Untouchables: ‘Socially, they are lepers. Economically, they are worse than slaves.

Also read: How Ambedkar was both ‘Dalitised’ and ‘Brahminised’ by Indian ruling class to own history

Religiously, they are denied entrances to places we miscall “houses of God”.’ He gave more examples of the discrimination faced by Untouchables, and said it was a ‘wonder’ that they were able to survive, and they had remained within the Hindu fold. Gandhi also mentioned, with approval, a suggestion made to him by Ambedkar during their conversations in Yerawada Jail: ‘Let there be no repetition of the old method when the reformer claimed to know more of the requirements of his victims than the victims themselves.’ He disclosed that Ambedkar had given him ‘harrowing details’ of the discrimination he had suffered. ‘I felt the force of his remarks,’ Gandhi said. ‘I hope every one of my readers will do likewise.’

Ambedkar latched on to such statements and read them as signs of a ‘revolutionary’ change in Gandhi’s outlook. Writing on 14 November 1932 to readers of Janata, when he was on his way to London for the third RTC, Ambedkar said:

“Most of my time goes in reading Gandhiji’s untouchability-eradication statements …. Reading some of the thoughts in the statements, I feel a certain kind of surprise. One can see a revolutionary change in Gandhiji’s thoughts. Gandhiji should now be called ‘our man’, because he is now speaking our language and our thoughts …. [Reading some of the views] I feel as if I am reading English translations of articles published in Janata, Samata or Bahishkrut Bharat …. I am reminded of something that took place in Poona recently. After signing the Poona Pact, all of us went to Yerawada Jail to tell Gandhiji the happy news. Speaking to Gandhiji, Shri Rajagopalachari said, ‘Dr Ambedkar has become one who shares our views.’ Gandhiji remarked, ‘How nice!’ But now, after reading Gandhiji’s statements, I feel that, rather than saying that I had become a follower of Gandhiji’s views, would it not be closer to the truth to say that Gandhiji’s views and ideology are getting aligned to our views and ideology? (Janata, 10 December 1932)”

In this way, the dispute between Gandhi and Ambedkar about who had the right to speak for the DCs receded into the background by the end of 1932. But it left a third issue open: about who had the better strategy to ensure that the unwritten part of the Poona Pact would be fulfilled. According to the view expressed by Ambedkar at the second Mahad conference, the strategy had to take into account the principles for reorganising the entire Hindu society. How these principles were to be promoted was crucial.

Also read: How Dalit leaders created rift between Ambedkar’s savarna wife and son after he died

Differences

On matters of strategy as well as principles, Ambedkar had fundamental differences of opinion with Gandhi, which became obvious in 1933. Even in 1932, when reconciliation was in the air, there were definite signs of an inevitable rift. In the letter written on 14 November to the readers of Janata, Ambedkar noted that though Gandhi had dropped his opposition to inter-caste marriage and dining, he had said that it could not be part of the national campaign against untouchability that was going to be launched. Gandhi’s argument was that while untouchability was a ‘canker eating into the very vitals of Hinduism’, restrictions on inter-caste dining and marriage were only some customs that stunted Hindu society. There was thus a fundamental difference between the two issues, and if inter-caste dining and marriage was included in the anti-untouchability campaign, it would become ‘overweight’ and lose direction. The inclusion might also be seen as a ‘breach of faith’, Gandhi said, as he had publicly opposed inter-caste dining and marriage in the past (CWMG 51: 343–44). Responding to this argument, Ambedkar remarked that Gandhi had not yet ‘properly’ understood that caste had a ‘reciprocal relation’ with untouchability (Janata, 10 December 1932).

In the same letter, Ambedkar also objected to Gandhi’s methods. In his first statement on untouchability, Gandhi had spoken about ‘resuming’ his fast if the unwritten ‘vital conditions’ of the Poona Pact were not carried out by Caste Hindus (CWMG 51: 341–42). Ambedkar said the fast would make no difference to scores of Brahmanical religious figures and their followers who would be glad to see Gandhi dead. Gandhi’s action was therefore likely to become a selfish act. It might increase his stature, but yield nothing else. ‘Gandhi should use his life in such a manner that it leads to real benefit for the Untouchables,’ Ambedkar wrote, touching upon the two basic questions that led to a parting of ways: What constituted real benefit for the Untouchables? And how was it to be achieved?

In their approaches to these questions, Gandhi and Ambedkar stood at distant poles, at different levels. Gandhi spoke of some sort of higher-order change among Caste Hindus that would lead to a change in their relationship with the DCs, without disturbing the Hindu social structure. Ambedkar, on the other hand, had his feet on the ground, and wanted immediate and permanent protection for the DCs from the everyday violence of caste.

Ambedkar’s approach became amply clear through one of his interventions in the Bombay Legislative Council soon after the signing of the Poona Pact. The occasion was a debate on a bill to turn village panchayats into local self-government bodies, with members elected on the basis of adult suffrage and enjoying some judicial powers. Ambedkar had many objections to the bill. Unlike Gandhi, who valorised the Indian village, Ambedkar thought villages were ‘saturated with local particularism, with local patriotism … that left no room for larger civic spirit’ (BAWS 2: 106). In that situation, adult suffrage was terribly inadequate for the protection of the DCs. They were a ‘small body of people, occupying a corner of a village’, who were ‘never looked upon as part and parcel of the village community’, and whose progress was always ‘looked upon with great jealousy by the rest of the community’ (111) Hence, it was absolutely necessary that the DCs were given ‘special representation in order to protect their rights’ (107). As for giving judicial powers to panchayat members, it was a ridiculous notion.

“A population which is hidebound by caste, a population which is infected by ancient prejudices, a population which flouts equality of status and is dominated by notions of gradations in life, a population which thinks that some are high, that some are low—can it be expected to have the right notions even to discharge bare justice? (BAWS 2: 109)”

Hence, what the Hindu nationalists described as an evil, and what Gandhi regarded as only a halfway measure for the DCs, was for Ambedkar a necessity for the DCs and all other minorities in the country. ‘Communal representation’ was going to be one of the ‘best parts’ of the forthcoming constitutional framework, he said.

“India is not Europe. England is not India. England does not know the caste system. We do. Consequently, the political arrangement that may suit England can never suit us. Let us recognise that fact. And I would go one step further … in saying that, whatever other students of Indian politics may say, I maintain the proposition that if there is any good in the Indian constitution that is going to come, it is the recognition of the principle of communal representation …. I want a system in which not only will I have a right to go to the ballot box, but I will have a right to have a body of people belonging to my own class who will be inside the House, not only to discuss matters but to take part in deciding issues. I say, therefore, that communal representation is not a vicious thing, it is not a poison, it is the best arrangement that can be made for the safety and security of the different classes in this country. (BAWS 2: 114)”

Key to Abbreviations

BAWS — Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches, multiple volumes

CWMG — Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, multiple volumes

Bibliography

Pyarelal. 1932. The Epic Fast. Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House.

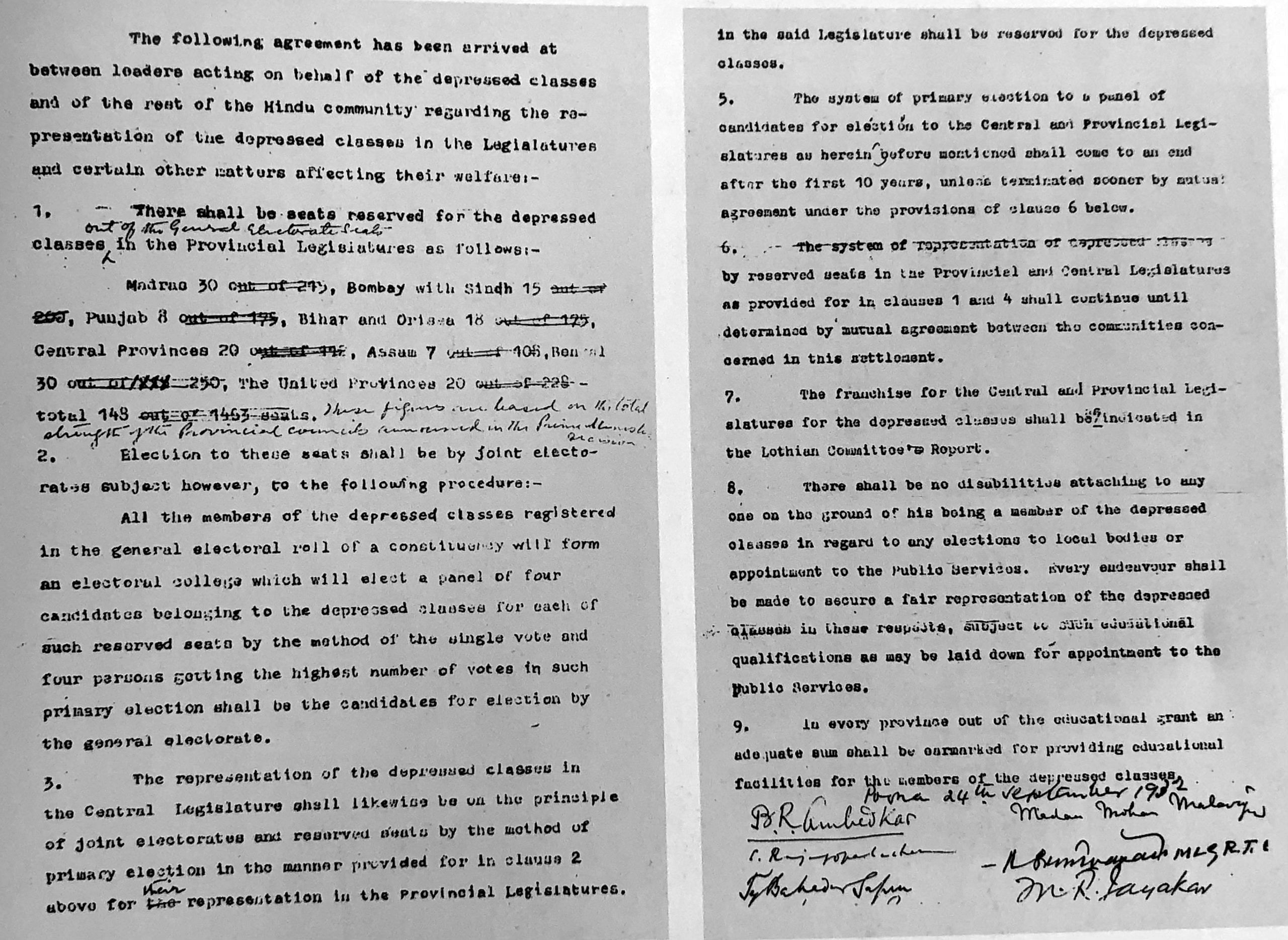

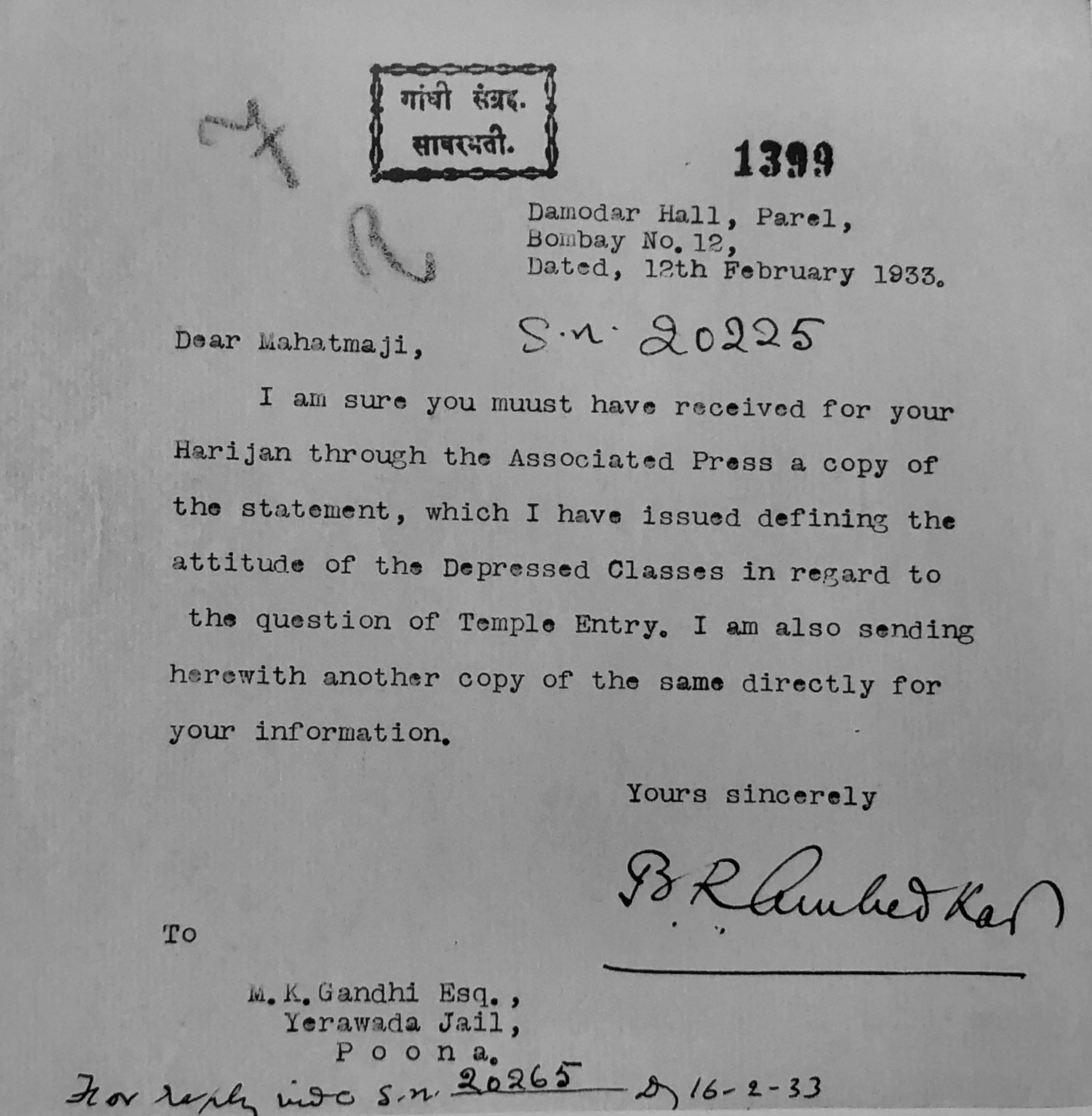

This excerpt from Ashok Gopal’s ‘A Part Apart: The Life and Thought of B.R. Ambedkar’, has been published with permission from Navayana. These pictures are for one-time use in ThePrint, and cannot be reproduced or shared anywhere without permission. We are in an agreement with—and in debt to—Vijay Surwade, the archivist from Thane, for these.

This excerpt from Ashok Gopal’s ‘A Part Apart: The Life and Thought of B.R. Ambedkar’, has been published with permission from Navayana. These pictures are for one-time use in ThePrint, and cannot be reproduced or shared anywhere without permission. We are in an agreement with—and in debt to—Vijay Surwade, the archivist from Thane, for these.