The intersection between class and caste in Tamil Nadu was not unique, but it was intense and called for vigilance on the part of a state that was publicly committed to egalitarian justice. My first posting in the state, being in Thanjavur, was a godsend. It brought me into what may be called the ‘heart cave’ of its life.

Modernizing paddy cultivation was the collector’s day’s chore and nightly dream. His tireless propagation of new strains of rice developed in Aduthurai, the rice research station in his district, was the talk of the state administration. Chief Minister Karunanidhi, on a visit to the district, described the collector as ‘the Antony who is besotted with his own Cleopatra—agriculture’.

Antony was also a turbine of energy for something besides agriculture. Family planning was his passion, and spreading the message of the small family was his creed. That he was, as a consequence, the butt of friendly jokes did not dampen his ardour. I did not see then, but do now, that this would not have been easy, theologically, for a Syrian Christian and a devout one at that. A crucifix dangled on his chest from a gold chain at all times. Antony made me see for sure that all development would be futile if our numbers continued to grow unchecked. If our birth rate is showing signs of stabilizing today, it is in no small measure due to the likes of Antony, who made family planning a state priority at the key district level.

Also read: Nehru’s liberal import policy took a restrictive turn in 1957. Inflation was the catalyst

Soon after joining duty in Thanjavur, I was told I must, as assistant collector (Training), draw a tour programme for myself covering all the training tasks I am supposed to do and send it to the collector for his approval. So, I prepared the list and sent it with a covering line of which read something like this: I forward herewith my draft programme for your approval. The piece of paper came back super-fast with his approval and—a reprimand. ‘A/C Trg to note: to your superiors you submit, to your equals you transmit, and only to your subordinates do you forward.’ Hierarchy teaches its lessons. The collector’s intention in sending that reprimand was to let many others who will see that note on its way to me and later know that I had been given a ticking off.

But there was another piece of vital counsel he gave me, in confidence.

‘Gopal, I must tell you that ours is a very caste-conscious state. Now, I do not know what you regard as your caste. But given that you are half-Gujarati and half-TamBrahm, let me advise you, right at this starting stage of your career here, to see yourself and position yourself as a north Indian allotted to Tamil Nadu and NOT as a TamBrahm. I see from some indications that you are giving that you have a TamBrahm slant to you. Get rid of that. The sooner you do that, the better it will be for you. And one more thing: learn up about the castes of the state, which caste is dominant in which district and the like.’ I followed the advice about not seeing myself and being seen as a TamBrahm, but I never quite managed to master the caste break-up in the state. A lack that has weakened me and my official effectiveness.

Amma set up a small home for me in Thanjavur town, cooking meals for me and keeping me cradled in her loving care. She was fifty-nine at the time, not a great age, but diabetes had enfeebled her, and I am, looking back, in awe of her having adjusted to what may be called mofussil life for my sake. The house was small, as I said, but new, and Amma furnished it simply but with great refinement. The only problem was the kitchen stove. There was no gas then, and we had no electric cooking systems in the house. An open chulha with a coal fire would have to be lit by her. This would take time and fill up the kitchen with smoke each time it was lit, turning her eyes red. But once it got going, it yielded the most delicious fare.

This was the year India was celebrating Mahatma Gandhi’s centenary. One ingenious method used by the Indian state was to assemble a photo exhibition on wheels. A Gandhi Centenary ‘Special’ coursed through the country bearing these photo panels and came to Thanjavur as well. For my mother and me, this came with an additional joy—my cousin Manu Jaisukhlal Gandhi, who was on the train as, I imagine, a living exhibit, came home and also met Antony, who took time off from paddy and family planning to meet this Gandhi kin on Gandhi’s centenary.

At the national level, 1969 saw the bizarre phenomenon of Mrs Indira Gandhi ditching her own party’s candidate for president of India—N. Sanjiva Reddy (1913–96). She certainly had her reasons, but the optics of it all were bad. And Vice President V. V. Giri (1894–1980), a highly deserving candidate, announced his own candidature unilaterally and got the prime minister to transfer the majority of Congress votes to him on the principle of ‘conscience vote’. There was little work for conscience in the whole business, only for opportunism. And, listening to radio news in my Thanjavur dwelling, I rued Reddy losing the election, ayyo, for all wrong reasons even as I could not but hail Giri winning, though for all wrong reasons.

The split in the Congress that followed, the resignation in high dudgeon of Deputy Prime Minister Morarji Desai, the nationalization of fourteen banks, and the launching of the hollow and wholly demagogic slogan of ‘Garibi Hatao’ (banish poverty) all marked the beginning of realpolitik in India.

Nehru had died in 1964. But his soul was buried by his own political legatees in 1969. The year in which Gandhi would have turned 100.

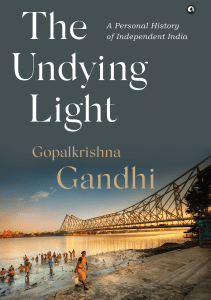

This excerpt from ‘The Undying Light: A Personal History of Independent India’, by Gopalkrishna Gandhi, has been published with permission from Aleph Book Company.

This excerpt from ‘The Undying Light: A Personal History of Independent India’, by Gopalkrishna Gandhi, has been published with permission from Aleph Book Company.