A kind of hand-fan used since antiquity to drive away insects and create a cool breeze, the fly-whisk is associated with power, divinity and purification in the Indian subcontinent. Fly-whisks typically comprise a handle that is mounted with brushed cotton, silver thread or animal hair, as in the chowrie; specifically yak-tail hair as in the chamara; or peacock feathers as in the morchal. These have been used by attendants to fan nobility in Indian royal courts — including high-ranking British colonial officers visiting princely courts — from at least the fourth century BCE to the mid-twentieth century CE, and were valued as early medieval trade objects. They are also used ritually to fan temple idols and sacred objects such as the Sikh holy book in gurudwaras, and are a common motif across religions in Indian visual culture.

Fly-whisks were often made as a pair, presumably owing to their use by two attendants

standing on either side of a ruler in court. A typical chowrie has a slim handle between 40

and 60 centimetres long that tapers towards the bottom, whereas a morchal usually has a

shorter and thicker handle. The fibres of the whisk are generally fixed, using small grips, into a cup-like head that is attached to the top of the handle in various ways, including

sometimes a metal tang extending into the handle. The materials used to construct the

handles of chowries and morchals range from wood to more expensive materials such as

beaten silver, gold, copper, ivory, nephrite jade or banded agate. They are also often

decorated with engravings or repoussé motifs, or inlaid with precious stones. Mughal

chowrie handles feature extremely precise, decorative naturalistic carvings in the

symmetrical, detailed style typical of the period, depicting flora such as marigolds, lilies,

poppies and cypress branches, and the cup itself is often stylised as a blooming flower.

Notable specimens of Indian fly-whisks are part of museum collections around the world.

The handle of a chowrie from the Rajput courts of Rajasthan, now housed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) features kundan work with diamonds set in gold

foil, and transparent green enamel. Some specimens of the Sikh ceremonial chowrie orchaur sahib feature handles made of the long, curved horn of the ibex, mounted with silver cups to hold the whisk. One exceptional specimen of a Mughal chowrie from the eighteenth century, housed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, is made entirely from a single elephant tusk — including the fibres themselves, which are created by finely shaving the ivory.

Another ivory chowrie from the Mughal court, in the Saint Louis Art Museum collection, features hairs made of slivers of whale baleen, a bristly keratinous filter or sieve found in the mouths of baleen whales. These chowries were likely made by craftsmen based in Murshidabad, the Mughal capital of Bengal, which was home to specialised workshops for ivory and woodworking. A much simpler chowrie from nineteenth-century Assam in Northeast India is housed in the British Museum in London — attributed to the Naga people native to the region; it features a slim, straight wooden handle wrapped tightly in copper wire and mounted with goat hair.

A chowrie featuring white yak-tail hair as the whisk is called a chamara — a Sanskrit term

that also refers to both the animal and its bushy tail, and is sometimes applied to ceremonial chowries in general. The chamara enjoys a special place of importance in Indian history and visual culture. Ancient and pre-modern Indian sculpture often features attendants holding chamaras flanking figures of authority. They are seen, for example, in the depiction of Yama at the fifth-century Shiva temple in Bhumara, Madhya Pradesh, or that of a nagaraja or serpent-king in a medallion on the railing of the Bharhut stupa, dated to the second century BCE. Nature spirits — yakshas and yakshis — too are depicted with chamara in hand. The chamara remained in use by royalty up to the Mughal dynasty.

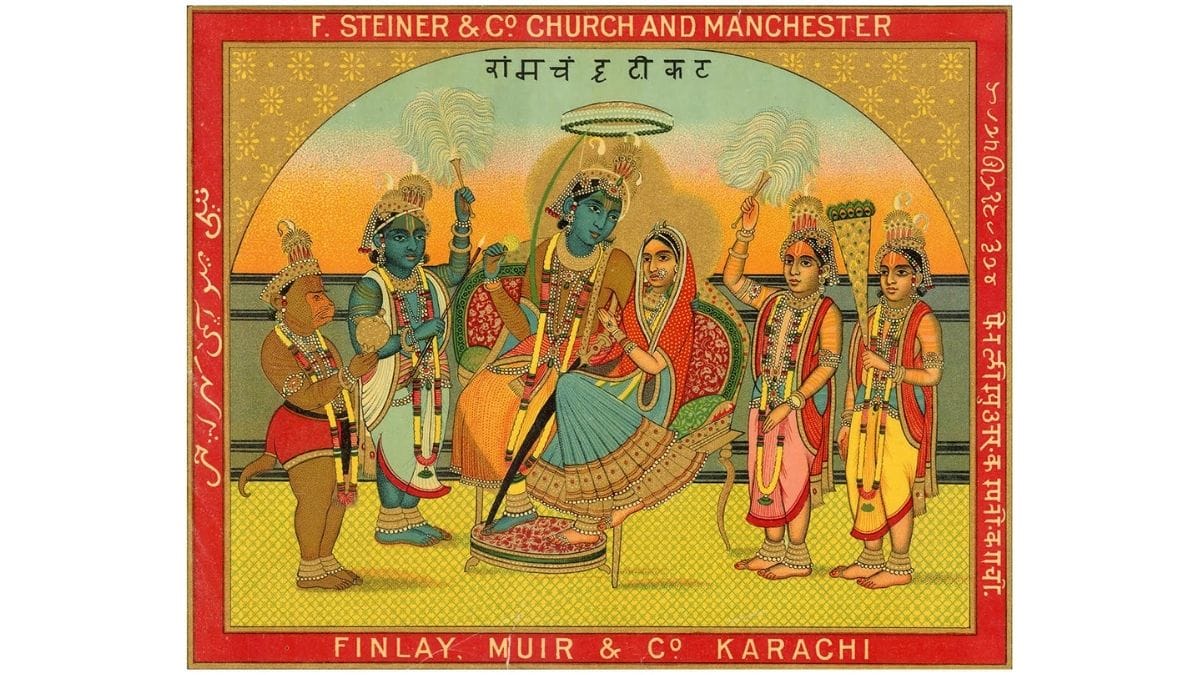

The morchal derives its name from the Prakrit mora, meaning peacock, and draws special

symbolic significance from the peacock feathers forming its whisk. Figuring prominently in

Vaishnava and Shaiva imagery, the peacock feather appears across varied traditions of the

subcontinent, from folklore to Sanskrit literature, as an especially healing or purifying object or symbol.

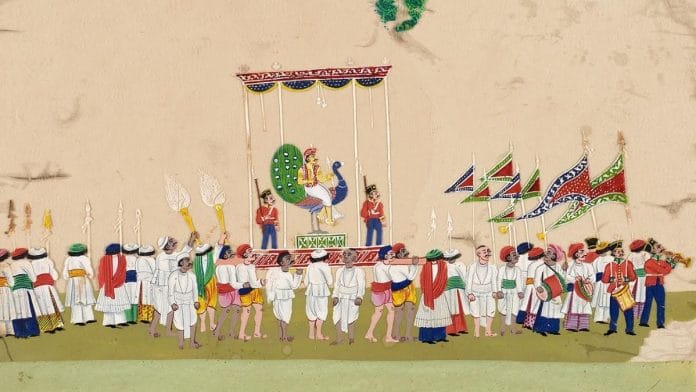

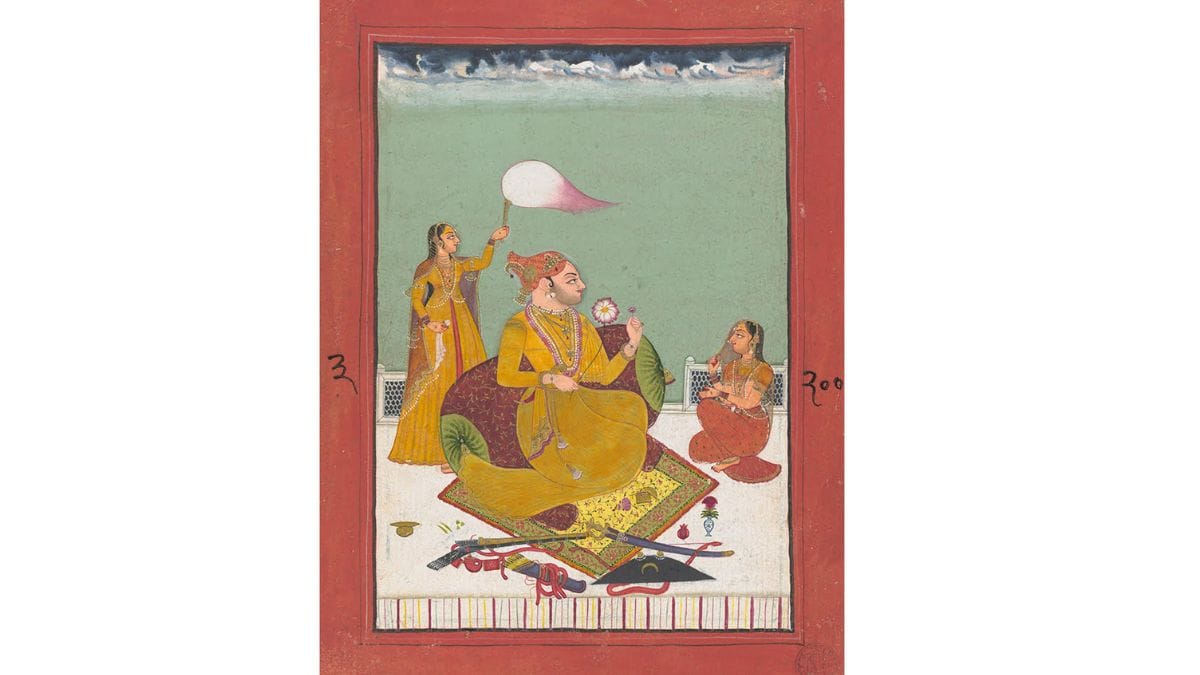

Chowries, chamaras and morchals frequently appear in Indian art as symbols of royalty or

divinity. In the tenth-century Sanskrit collection of folk tales and legends Kathasaritsagara by Somadeva, the king Naravahanadatta is born with birthmarks resembling chowries and

parasols on his feet — both auspicious omens signalling his future as a great king. Miniature paintings from Mughal and Rajput courts depict fly-whisk bearers or chamaradars alongside royal figures. Some scholars have suggested that the fly-whisk was just as symbolic of royal power as the parasol, the crown or the throne, and could represent the ruler’s presence and authority even when he was absent. Some scholars argue that by extension, chowrie-bearers — such as the second-century Didarganj Yakshi — themselves occupy a place of importance as divine guardians of creation, rather than being simply subservient figures.

Historical and literary sources mention fly-whisks as valued objects in trade. The ninth-

century Arab historian al-Masudi mentions ‘al-chamar’ as an item commonly exported from

the subcontinent. The eighth-century Prakrit text Kuvalayamala was written by the Jain monk Uddyotana-suri mentions the trade of fly-whisks in eastern India.

Fly-whisks also have a place in religious ritual — in Hinduism and Buddhism, they came to

symbolise the clearing away of earthly worries and the purification of the soul. The

Digambara Jain tradition lists the chamara among its eight auspicious symbols. In Sikhism, the chamara is referred to as the chaur sahib and is a fixture in most gurudwaras, used to fan the Guru Granth Sahib, the faith’s holy book, in which it appears frequently as a symbol of both divinity and service to divinity. The fly-whisk also finds a place in the Ka Shad Mastieh dance of the Khasi community of Meghalaya, a war dance in which the male dancers hold a sword in one hand and a fly-whisk in the other.

Besides the specimens described above, other examples of fly-whisks from the eighteenth to early twentieth century can be found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum, London; and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City.

This article is taken from the MAP Academy‘s Encyclopedia of Art with permission.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit, open-access educational platform committed to building equitable resources for the study of art histories from South Asia. Through its freely available digital offerings—Encyclopedia of Art, Online Courses, and Stories—it encourages knowledge-building and engagement with the visual arts of the region.