The year 1982 was the turning point in Modi’s career. The gold medal at the Commonwealth Games was the recognition he needed on the big stage. Indian sport was looking up, and this was to mark a decade of achievements. It began with Padukone’s All-England title, followed by India hosting the 1982 Asian Games, Kapil Dev’s team winning the 1983 World Cup and Sunil Gavaskar leading the side to a triumph at the 1985 World Championship of Cricket. The 1986 Seoul Asian Games saw P. T. Usha claiming four gold medals. It was the best time for young minds planning a career in sports.

For Modi, it was enough reason to justify the faith his predecessors had in him. There was a flourish that marked his movements on the court. He had the grace and the tenacity to match his opponents. He loved to ground the opposition with his untiring stamina. Modi’s hard work on the court reflected his sound training.

Modi was the youngest among eight siblings. He had five brothers and two sisters and was the darling of his family. His father, Syed Meer Hassan Zaidi, worked in a sugar mill, and his brothers supported and funded his badminton career. His family believed Modi had the potential to be a global star, and he lived up to their expectations. The Commonwealth gold and the Asian Games bronze in the same year proved Modi’s capacity to succeed on the big stage.

‘His consistency was his strong point. He had grown as a player in two years, and the victory against Prakash only confirmed his potential. He had the game to unsettle his opponents. His forte was the jump-smash, and I was very impressed with his overall game,’ observed Khanna. Most experts believed that Modi had the resilience to emulate Padukone.

Not similar in their play on court, Modi and Padukone had a few common traits. They loved tiring the opponent with their solid defence and a sudden smash. Modi could have been better than Padukone at the net. Padukone was a master at the drop and cross-court placements. Modi would look to stretch the rival, something he had learnt from close observation. Modi also excelled with his backhand, working on this aspect to stun his opponents.

According to Shirish Nadkarni, ‘Similarity was between Modi and Goel. Goel took Modi under his wing as his protege. You can see Goel’s strokes in Modi’s gameplay. Modi’s quality of stroke play was far superior to that of Prakash. Prakash had attributes like a powerful mind, excellent temperament and many deceptive strokes. He used to hold his wrist until the last moment and then flick it. His flick toss from the net was exceptionally superb. He could dribble as well as flick behind with the same action. And that is what defeated Liem Swie King in the 1980 All-England final.’

Also read: You don’t have to be a Hindu to be moved by Kumbh Mela. It is about the simplicity of faith

Modi’s domination at the national level was complete, like Padukone’s. While Modi was alive, the talented Vimal won the title only once. Modi had become the junior national champion when he was just fourteen. His coach, P. K. Bhandari, had trained him well. Padukone had stopped playing in India after the defeat at the hands of Modi, who, however, did not do justice to his talent, winning only three international titles – Austrian Open (1983 and 1984) and USSR Open (1985) – other than the Commonwealth Games gold.

‘Being slender and lacking strong shoulders, Modi relied on subtle timing rather than raw power. His game can be compared with tennis star Ramesh Krishnan’s style of play, outsmarting the opponents with placements by engaging them in long rallies,’ remembered Suri. ‘Many compare his game with his fellow Indian Railways badminton star Suresh Goel. Both being at camps together and practising together for hours, Modi picked up the nuances of the game from Goel. Besides, both were coached by the legendary Dipu Ghosh, thus the similarity in their play.’

Recalling Modi’s strong points on the court, Suri noted, ‘The advantage of Modi was that he had a powerful backhand, which is generally a weakness with many top players. With a flick of the wrist, he could send the shuttle to the deep corners of the court, to catch the opponents on the wrong foot repeatedly. Because of his stamina, he could hold his own during long rallies and often finished a rally with his patent forehand cross-court half-smash with a jump. That pose appeared in newspapers countrywide time and again during his playing days. Maybe the lack of power did have disadvantages when playing against international players. But there was limited international exposure back then, unlike today’s players. If he had been playing in today’s times, maybe his achievements would have been far greater.’

According to Sanjay Sharma, Padukone lost to Indian players only once each from 1973 to 1980 – Iqbal Maindargi in 1975 and Modi in 1980. Even though Modi craved good facilities in Uttar Pradesh, his early years of learning the game from Suresh Goel helped him understand the game better. ‘Modi was a laidback, cool and calm contender. He had some lovely strokes and an outstanding defence. He would have played much more for India, but for his untimely death.’

For Ameeta, Modi’s example and his relationship with Padukone are touching. She claimed never to have seen the kind of respect Modi had for Prakash. ‘He always called him Bhai Saab (elder brother) and never took his name. He had the same respect for Suresh Goel, a legend.’ Ameeta felt Modi’s game was on the lines of Goel. ‘Modi learnt the game from Suresh. He respected Ami so much. That is missing today. We had this community living (at camps). Boys and girls going for walks to the gate at Patiala NIS, singing, joking, and teasing. That was the bond. That special feeling of being together.’

Former national junior champion Malvinder Dhillon remembers Modi as a gentleman who would not harm a fly. Modi’s calm exterior reflected his inner self. There was nothing that could perturb Modi, not even a close defeat. He would take it in his stride and set out for the next battle. Dhillon said, ‘Modi was extremely fit. He would play basketball to improve his flexibility and cycle to attain a high standard of fitness. Modi knew that endurance was an integral part of being a successful player. Modi was a straightforward boy, and I loved him because he made it a point to bring me racquets from his trips abroad. Modi had great respect for the rivals.’

The killing of Modi when he was twenty-five is a dark chapter in Indian sports. He envisioned a career and would have proved a great asset with his deep understanding of badminton. As Dhillon said, ‘Modi would have been ideal to groom youngsters because of his work ethic and a solid background of hard work and discipline. We sorely missed his wisdom.’

For Suri, the biggest question that rankled Indian badminton lovers was how Modi’s career would have panned out had he not fallen in love with Ameeta Kulkarni and ultimately married her in 1984 when he was twenty-two years old. Modi was at the peak of this prowess then, just about gaining ascendency internationally after having won the 1982 Commonwealth Games gold medal in Brisbane to add to a bronze medal in the 1982 Asian Games in New Delhi. He subsequently won the Austrian Open titles in 1983 and 1984 and the USSR title in 1985.

‘He was virtually unbeaten in India from 1980 till his death in 1988, having won the national title eight times in a row, when he defeated Padukone. But his CV is bereft of three major crowns…an Olympic medal, an All-England title and a podium finish in the Thomas Cup,’ said Suri.

Modi’s friends in his home state have no doubt that Modi could have surpassed Padukone’s achievements, won the All-England at least once and have had many more international titles in his kitty. ‘There are enough reasons for me to believe that Modi’s achievements on his home soil, where he was invincible, are legendary. But a thought always persists in the mind that his career and life would have had many more glorious moments than he ended up with. If he were alive today, he would have undoubtedly guided today’s generation like Prakash, Vimal, and Gopi Chand have been doing,’ observed Suri.

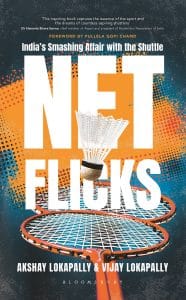

This excerpt from ‘Net Flicks: India’s Smashing Affair with the Shuttle’ by Akshay Lokapally and Vijay Lokapally has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.

This excerpt from ‘Net Flicks: India’s Smashing Affair with the Shuttle’ by Akshay Lokapally and Vijay Lokapally has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.