But the grandparent who had the deepest influence on me,’ Sudha told Murthy, ‘was my paternal grandmother, Amba, whom I called Ajji. Ajji was widowed early in life. She looked like any other traditional widow of the time, with a white sari that covered her shaven head. I will always remember the sadness in her voice when she told me what had happened to her once her husband died. “No one asked my permission before chopping off all my beautiful hair.” Until then, I’d never thought about the sad plight of widows. Ajji opened my eyes to that – and to many other things.’

Ajji’s spirit was undaunted by the hand fate had dealt her. She decided to become a midwife, taught herself the necessary skills, and delivered over a hundred babies. She helped women of all castes and religions. She never turned down someone who needed her help; whether they were rich or poor did not matter to her. Day or night, she was ready to respond to whoever came knocking at her door.

Endowed with practical intelligence, Ajji had developed a series of processes to ensure the safety and success of her ‘patients’. People could not visit the mother unless they were healthy and freshly bathed. Everything that came in contact with the mother was cleaned with turmeric. She made the new mother drink water that had been boiled with an iron rod in it to replace iron lost through bleeding.

Ajji treated the entire childbirth process as normal and discussed it frankly with her granddaughters. Sudha even accompanied her to a midnight delivery once – an adventure that left a deep mark on her. It was no coincidence that both Sudha’s father, Dr R.H. Kulkarni, and her elder sister Sunanda decided to become gynaecologists. When Sudha herself opted for engineering, a field of study that was considered inappropriate for women, she remembered what Ajii had demonstrated through her lifestyle and stood firm against all the relatives who tried to change her mind.

Ajji also said to Sudha, ‘A woman can do a man’s job. But a man cannot do a woman’s job.’ It was a statement that Sudha would think of at a crucial moment in her life.

The values that Ajji stood for and her out-of-the-box thinking were to have a strong influence on Sudha. Her grandmother was a rebel disguised as a traditionalist – a canny strategy that Sudha recognized as very effective. She herself would employ it at the right time in her life.

Sudha’s upbringing was quite exceptional for a young Indian woman of that time because she was given the freedom to read what she liked, to go outside the house just like her brother Shrinivas, and to travel alone in buses when she was as young as eight years old. Later, when she decided to cut her hair short and wear pants, no one stopped her. Her father discussed menstruation – considered an ‘unclean state’ in conservative families – frankly and openly with her and her sisters when it was the right time, pointing out that it was just a biological condition and nothing to be ashamed of. As a result, from a young age, Sudha developed confidence, a strong will, and an ability to think analytically and independently. She was also very courageous. One foggy morning, when she was walking to school by herself, a man tried to snatch her gold earrings. Instead of being afraid, Sudha yelled fiercely, berating him, and smacked him hard with her umbrella. The startled thief ran away as fast as he could.

Murthy, thinking about how strictly his own sisters had been brought up with the dual ‘virtues’ of obedience and docility, and with a suitable marriage as their only goal, said to Sudha, ‘Do you realize how lucky you are to come from a family where you were never held back because you were a girl? Where you were actually encouraged to study and to stand up for yourself ?’

‘I do,’ Sudha said, suddenly serious. ‘It was a true gift. That’s why I must make the most of it.’

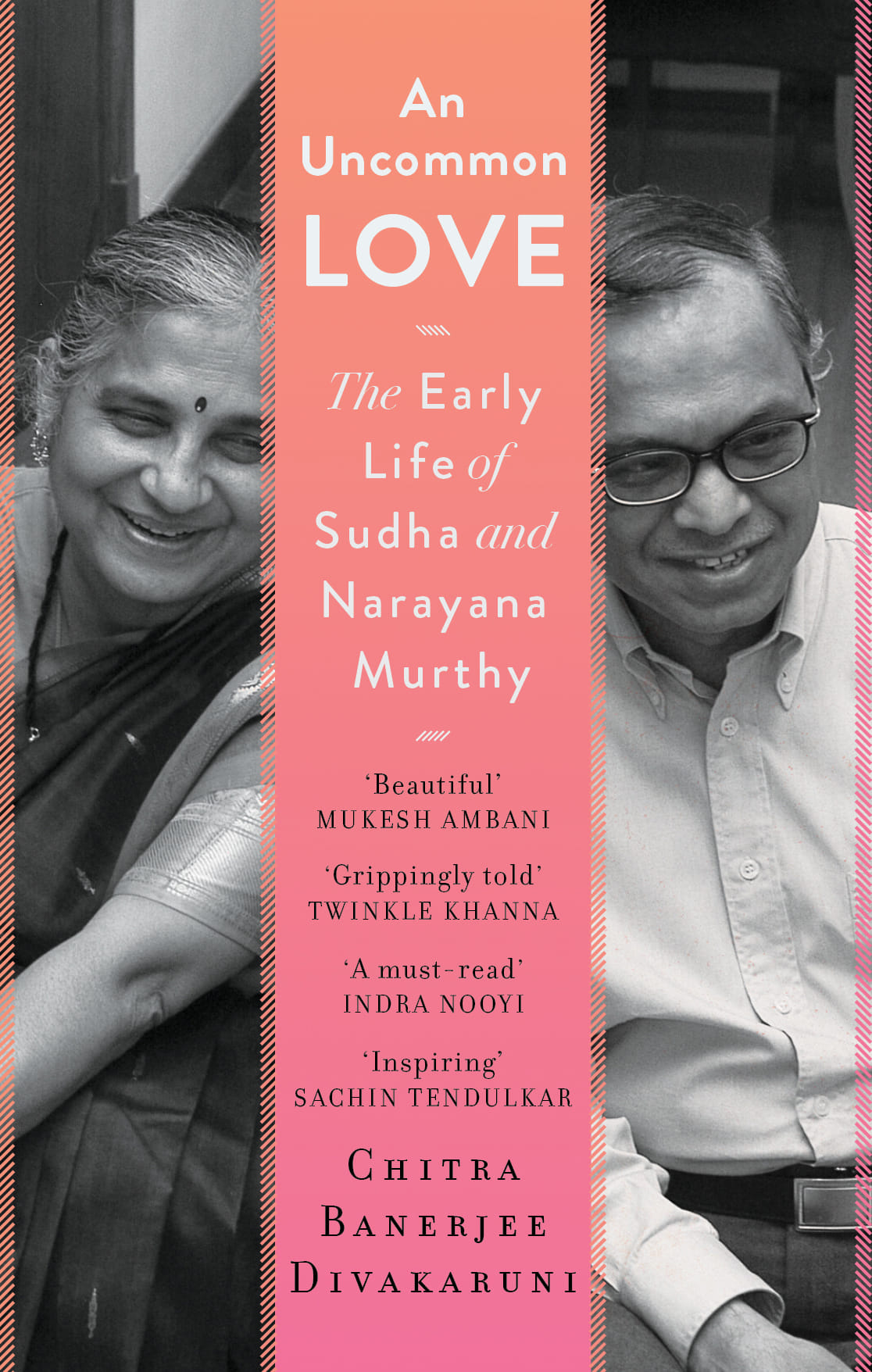

This excerpt from Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s ‘An Uncommon Love: The Early Life of Sudha and Narayana Murthy’ has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books.

This excerpt from Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s ‘An Uncommon Love: The Early Life of Sudha and Narayana Murthy’ has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books.