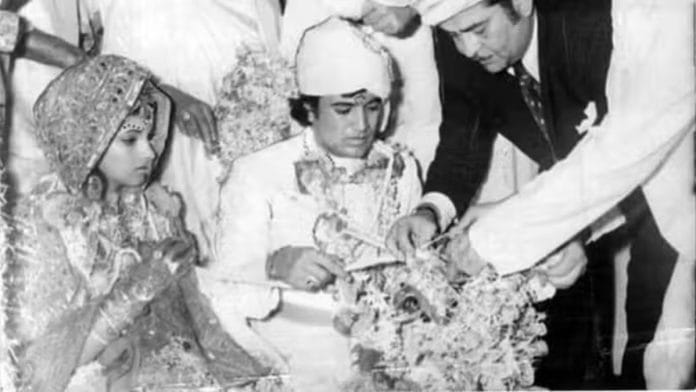

The wedding film of Rajesh Khanna and Dimple Kapadia set a trend among the wealthy in Delhi to record weddings with 16mm or Super 8 cameras. However, this development evinced little commercial potential, as film stock and camera equipment were available in limited supply and few could afford access to projection facilities (Sengupta 1999, p. 281). Moreover, developing and processing took time, and labs did not prioritize home movies; for instance, Mahatta, the oldest photography studio in Delhi, boasted in-house black-and-white and colour processing labs, but I was told that only weddings of employees or those of established clients making special requests were processed. It is only with the advent of analog video technology in the 1980s that marriage videography spread widely amongst the middle classes.

Marriage videos emerged as a new form of narrative production for wedding ceremonies. These videos had a running time of two or three hours and videographers used video technology to create a distinct form. Marriage videos are usually edited from around six hours of footage. Fragments are selected to construct a coherent narrative. The result is a video structure with archetypical narratives of the wedding as well as a commentary on the narrative through a juxtaposition of selected scenes, images, and audio. The video narrative, thus, has strong links to film narratives of weddings, especially in its incorporation of film songs, plots, images, and aesthetics into a complex structure interwoven with the marriage story.

The Emergence and the Infrastructure of the Marriage Video as a Commercial Enterprise

As noted in the introductory chapter, the Asian Games held in Delhi in 1982 marked the arrival not only of colour television but also of video technology in India. The entry of video initiated a shift in the perceptual regime of the spectator, as media started to be consumed in the home. The games also led to a liberalization of the tariff regime for electronics, with import restrictions relaxed on video cassettes, video recorders, and television sets. Television enabled the expansion of video technology, opening up possibilities for individuals to develop different media practices and creating space for alternative modes of production and distribution.

Video technology created new possibilities for highly reproducible and portable ‘small-media’ practices (Battaglia 2014, p. 78). These practices circulated through narrow-cast networks, creating ‘strong bonds’ among different groups of people (Battaglia, p. 74). One such small media form is the marriage video. In her discussion of the independent documentary, Battaglia uses the concepts of ‘expansive realization’ to describe the multiplication of practices enabled by video and ‘residual media’ to represent the material qualities of video with regard to professional film production (Battaglia, p. 72). As residual media, video technology builds on previous technologies. In the case of the marriage video, it is both the home movie and the Hindi film that function as residual forms, shaping this media practice.

Also read: From Nazi-era Vienna to Ludhiana. How an Indian helped Jewish families escape

Video promised to be the new frontier in the image production and representation of the wedding. Many photographers became entrepreneurs and quickly acquired video cameras. Their clients viewed video as a continuous stream of still images, leading them to conclude that wedding videos could provide a far greater number of images much more cheaply than photography (Zeff 1999). Many photography studios, such as Mahatta and Prem, extended their oeuvre to wedding videography. Emerging alongside these studios was what I term the videographerentrepreneur who saw in this new medium the opportunity for a commercial enterprise.

At this point, it is imperative to emphasize that the story of the development of the marriage video is also the story of male practitioners who shared a common desire to make films but did not want to shift production to Bombay. The advent of video cameras, VCRs, and VCPs in the 1980s, combined with a more liberal regime of electronics tariffs, provided local entrepreneurs and aspiring film-makers with new opportunities. However, duties remained high, at around 250 per cent, and cassettes needed to be pre-booked to ensure they were available on the day of the wedding. This situation made the videographer-entrepreneur turn to grey markets such as Chandni Chowk to procure equipment and pre-used tapes at affordable prices. As Harish Sawhney, a marriage videographer in the 1980s and now a marriage video editor, stated:

[S]ee at that time, video was a new thing and it was very expensive. Anybody in this business had to consider output and return when buying this new technology. The equipment was procured from the photo market at Chandni Chowk, New Delhi. It was a grey market where used cameras and cassettes from England and Germany were sold. These cassettes contained recording of television shows and were later discarded. We used these discarded cassettes by erasing the recording. In a way, we recycled this equipment.

These new developments made possible the rise of the marriage video as a commercial enterprise, no longer restricted to the domain of the elite, but making its way into the middle-class home. The new breed of marriage videographer-entrepreneurs hailed from middle-class backgrounds. Former marriage videographer turned government employee B. S. Jain said:

[F]or me the marriage video was a good idea for a start-up. In this business in terms of investment, the only cost that is factored in is the purchase of the camera, unlike other businesses where costs of production, sale, and marketing have to be factored in. From the earning point of view there is no risk involved.

The videographers used community connections and capitalized on word of mouth to popularize their business. It was common for families to choose videographers to shoot weddings based on kinship or friendship networks. For instance, Prem Chabbra, who also owned a studio named Prem—perhaps cannily capitalizing on the reputation of the large Prem studios—drew on contacts through his father, a prominent property dealer in Delhi.13 Others built contacts by using their community identities, while one videographer claimed it was his educated background that attracted customers to his business.

Many videographerentrepreneurs insisted that customers essayed a role in shaping the features of the wedding video and that their preferences dictated the production of the videographer, not the other way around. A good work ethic was also necessary to sustain word-of-mouth recommendations for one’s business. As Prem Chabbra succinctly put it: ‘Kaam (work), nature, and behaviour’14 were the three most important things a videographer needed for publicity. As a profession, marriage videography was considered tough, requiring hard work. For example, a videographer committed to a shoot six months in advance, and needed to be present no matter what happened in his personal life.

Although video cameras were not produced or marketed in India, budding wedding videographers managed to acquire them, albeit at very high costs. The more advanced (and expensive) models had extra features such as on-camera wipes, dissolves, and fades, becoming more common as people replaced older cameras with newer ones in the market. The equipment initially used were National 50 and 100 systems, comprising three pieces: the camera, the VCR, and the battery.

This equipment was considered tough and bulky. Trying to achieve white balance on it was also difficult, and if not done correctly, the camera would start making circular patterns—what Harish Sawhney termed ‘jalebi’ after an Indian sweet which consists of countless sweet rings.15 In 1986, the JVC 5 came into circulation. It was a hand-held camera, and maintaining steadiness with it was a problem. Later, came the JVC 70 (also introduced in 1986), for which the videographer needed to use a shoulder pad, and which allowed for in-camera editing.

The lighting initially used for these videos was either a one- or threelight setup (a key, back, and fill light). The set-up was decided spontaneously depending on the nature of the venue. Shooting in daylight was more difficult as the light was harsh. To prevent backlighting, which created a halo effect, the videographer resorted to using black curtains on stage. Aesthetically, the lighting used for video creates a halogen effect with strong highlights. Such an aesthetic effect is generated because, in contrast to film, video has a lower latitude. In a frame with a bright spot and a dark corner, film can capture the details of the frame from the darkest to the brightest spot.

Video has a lower dynamic range and therefore works with strong highlights. Thus, to capture the details of the frame, videographers often needed to use halogen lights and wash both the couple and the wedding party with harsh frontal lighting; this would create a two-dimensional effect with a lack of depth, bleached out whites, and strong highlights. As Prem Chhabra explains: ‘The lighting, camera angle adjustments have to be according to the situation at that moment’.17 The presence of editing techniques has played a significant role in shaping the form of the marriage video. Wedding videography, like wedding photography, transformed the wedding by manipulating the images using video technology (Zeff 1999). Editing played a crucial role.

Videographers used camera effects, mixers, captured video clips, and special effects to craft and generate a distinctive set of images to signify the wedding ceremony. Initially, in the mid-1980s, videographers had no access to editing equipment, requiring great discipline on their part. They therefore had to be economical in planning the wedding shoot. Wedding videos were around three to three-and-a-half hours long, and the moment was captured as it was. The only addition videographers could make was the inclusion of sound or songs during the post-production stage. The editing was done on a VCR, using a television and two VCRs. The cassette with the recorded footage was inserted in the first machine, while the second had a blank cassette onto which was recorded the edited sequences. The editing was achieved by simultaneously pressing the pause button on the second machine.

In the late 1980s, in-camera editing became possible. Skala, a keyboard that came without an operating system and was used to make titles in-camera, was used regularly. For the titles, videographers used scenic posters and plastic letters of a kind now used in banquet halls, employing the keyboard to superimpose the titles over the scenery. A desi jugaadoo (or local informal) technique they employed was to mount and spin a bulb to keep the camera out of focus, which created colourful patterns that were superimposed onto the titles.

The other thing they did was to attach rings consisting of five to seven circles to the lens during the shooting; these would generate what they termed an ‘interesting effect’.18 In the mid-1990s, Doordarshan started selling off its equipment, and videographers began to edit with the Sony 350 mixer, an analog editing software using a keyboard to create numerical-based effects. Each number was associated with a particular effect. This initiated the use of effects such as fades, swipes, and split screens in the marriage video. It was only in the late 1990s that non-linear editing started to be used for these videos.

To illustrate the changing nature of the wedding video with the developments in editing technology, I will detail a viewing session at Harish Sawhney’s home studio where he was digitizing copies of these old wedding videos. The earliest videos were three hours or longer. They featured no effects and seemed to capture the ceremony as it was. The only manipulation possible during post-production was the layering of the soundtrack on the video. In the next set of videos, titles and different backgrounds began to appear, signalling the beginning of in-camera effects. The videos began with some sort of effect, like multiple coloured lights flashing in the background, with the titles of X weds Z emblazoned in the middle of the screen. The titles credits sequence allowed the most room for innovation in these sets of videos.

The introduction always featured some experiments with light to create interesting effects in the background, or they would use some sort of wallpaper and pan and tilt the camera. These backgrounds would then feature the title of the wedding video in different colours and fonts. The last set of videos indicated the presence of analog editing, where the videos enthusiastically illustrated the new tricks available to these videographers. One of the standout videos had the bride’s family welcoming the wedding party at a railway station.

The video started with the title sequence, fading to black before showing the bride’s family waiting at the railway station in a midlong shot. The next shot showed the train arriving. The bridal party was then seen in a mid-close-up, waiting with garlands for the groom’s party to deboard the train. With a swipe, a split screen appeared, the larger frame showing the greeting of the parties in a mid-long shot while the smaller screen positioned in the right-hand corner shifted between the viewpoints of the bride’s and the groom’s parties to capture their reactions. This was framed in a mid-close shot.

Sound played a crucial role not only in the development of the marriage video narrative, but also in its standardization. The songs used in these videos were popular Hindi film songs. For instance, ‘aaj mere yaar ki shaadi hai’ (‘Today is My Friend’s Wedding’) is used for the baraat, ‘baharo phool barse’ (meaning ‘Seasons of Spring’) for the garlanding, and ‘babul ki dua leti ja’ (meaning ‘Take your Father’s Blessings’) for the bidai (farewell ceremony). As the videographer Bal Kishen Goel stated:

All the classics are still being used. Like [the] shehnai tune, ‘meri yaar ki shaadi hai’ etc. The classics are eternal and always in demand. It also has to do with consumer expectation. For instance, you know that in a Punjabi wedding a Hansraj Hans song is always placed during the ‘doli’ (palanquin).

This excerpt from Ishita Tiwary’s ‘Video Culture in India: The Analog Era’ has been published with permission from Oxford University Press.

This excerpt from Ishita Tiwary’s ‘Video Culture in India: The Analog Era’ has been published with permission from Oxford University Press.