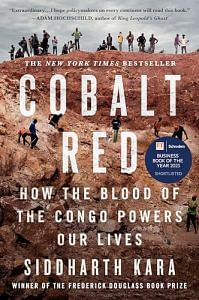

There is a frenzy taking place in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a manic race to extract as much cobalt as quickly as possible. This rare, silvery metal is an essential component to almost every lithium-ion rechargeable battery made today. It is also used in a wide array of emerging low-carbon innovations that are critical to the achievement of climate sustainability goals. The Katanga region in the southeastern corner of the Congo holds more reserves of cobalt than the rest of the planet combined. The region is also brimming with other valuable metals, including copper, iron, zinc, tin, nickel, manganese, germanium, tantalum, tungsten, uranium, gold, silver, and lithium. The deposits were always there, resting dormant for eons before foreign economies made the dirt valuable. Industrial innovations sparked demand for one metal after another, and somehow they all happened to be in Katanga. The remainder of the Congo is similarly bursting with natural resources. Foreign powers have penetrated every inch of this nation to extract its rich supplies of ivory, palm oil, diamonds, timber, rubber . . . and to make slaves of its people. Few nations are blessed with a more diverse abundance of resource riches than the Congo. No country in the world has been more severely exploited.

The scramble for cobalt is reminiscent of King Leopold II’s infamous plunder of the Congo’s ivory and rubber during his brutal reign as king sovereign of the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908. Those familiar with Leopold’s regime may reasonably point out that there is little equivalency between the atrocities that took place during his time and the harms taking place today. To be sure, the loss of life during Leopold’s control of the Congo is estimated to be as high as thirteen million people, a sum equal to half the population of the colony at the time. Today, the loss of life caused either directly by mining accidents or indirectly by toxic exposure and environmental contamination in the mining provinces would likely be a few thousand per year. One must acknowledge, however, the following crucial fact—for centuries, enslaving Africans was the nature of colonialism. In the modern era, slavery has been universally rejected and basic human rights are deemed ergaomnes and jus cogens in international law. The ongoing exploitation of the poorest people of the Congo by the rich and powerful invalidates the purported moral foundation of contemporary civilization and drags humanity back to a time when the people of Africa were valued only by their replacement cost. The implications of this moral reversion, which is itself a form of violence, stretch far beyond central Africa across the entire global south, where a vast subclass of humanity continues to eke out a subhuman existence in slave-like conditions at the bottom of the global economic order. Less has changed since colonial times than

we might care to admit.

The harsh realities of cobalt mining in the Congo are an inconvenience to every stakeholder in the chain. No company wants to concede that the rechargeable batteries used to power smartphones, tablets, laptops, and electric vehicles contain cobalt mined by peasants and children in hazardous conditions. In public disclosures and press releases, the corporations perched atop the cobalt chain typically cite their commitments to international human rights norms, zero-tolerance policies on child labor, and adherence to the highest standards of supply chain due diligence. Here are a few examples:

Apple works to protect the environment and to safeguard the well-being of the millions of people touched by our supply chain, from the mining level to the facilities where products are assembled . . . As of December 31, 2021, we found that all identified smelters and refiners in our supply chain participated in or completed a third party audit that met Apple’s requirements for the responsible sourcing of minerals.

Samsung has a zero-tolerance policy against child labor as prohibited by international standards and relevant national laws and regulations in all stages of its global operations.

While Tesla’s responsible sourcing practices apply to all materials and supply chain partners, we recognize the conditions associated with select artisanal mining (ASM) of cobalt in the DRC. To assure the cobalt in Tesla’s supply chain is ethically sourced, we have implemented targeted due diligence procedures for cobalt sourcing.

For Daimler, respect for human rights is a fundamental aspect of responsible corporate governance . . . We want our products to contain only raw materials and other materials that have been mined and produced without violating human rights and environmental standards.

Glencore plc is committed to preventing the occurrence of modern slavery and human trafficking in our operations and supply chains . . . We do not tolerate child labour, any form of forced, compulsory or bonded labour, human trafficking or any other form of slavery and actively seek to identify and eliminate them from our supply chains.

As scrutiny over the conditions under which cobalt is mined has increased, stakeholders have formulated international coalitions to help ensure that their supply chains are clean. The two leading coalitions are the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI) and the Global Battery Alliance (GBA). The RMI promotes the responsible sourcing of minerals in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights. Part of the RMI’s platform includes a Responsible Minerals Assurance Process that purports to support independent, third-party assessments of cobalt supply chains and to monitor cobalt mining sites in the DRC for child labor. The GBA promotes safe working conditions in the mining of raw materials for rechargeable batteries. The GBA has developed a Cobalt Action Partnership to “immediately and urgently eliminate child and forced labour from the cobalt value chain”2 through on-ground monitoring and third-party assessments.

In all my time in the Congo, I never saw or heard of any activities linked to either of these coalitions, let alone anything that resembled corporate commitments to international human rights standards, third-party audits, or zero-tolerance policies on forced and child labor. On the contrary, across twenty-one years of research into slavery and child labor, I have never seen more extreme predation for profit than I witnessed at the bottom of global cobalt supply chains. The titanic companies that sell products containing Congolese cobalt are worth trillions, yet the people who dig their cobalt out of the ground eke out a base existence characterized by extreme poverty and immense suffering. They exist at the edge of human life in an environment that is treated like a toxic dumping ground by foreign mining companies. Millions of trees have been clear-cut, dozens of villages razed, rivers and air polluted, and arable land destroyed. Our daily lives are powered by a human and environmental catastrophe in the Congo.

This excerpt from Cobalt Red by Siddharth Kara has been published with permission from Pan Macmillan.

This excerpt from Cobalt Red by Siddharth Kara has been published with permission from Pan Macmillan.