Among my acquired books published in the Jallianwala Bagh centennial is an anthology edited by Rakshanda Jalil, which contains an excerpt from Krishan Chunder’s (1914–1977) Urdu work of fiction, ‘Amritsar Azadi se Pehle, Azadi ke Baad’ (‘Amritsar Before and After Independence’), translated into English by Raza Naeem. In this story, we meet four Amritsari women named Paro, Zainab, Shyam Kaur, and Begum—four housewives who had stepped out in the evening to get groceries. The air was rife with the stench of gunpowder. Martial Law had been imposed after the fateful ‘Khooni Vaisakhi’.

In their haste to return home before curfew, the four women decided to take a shorter route through a lane. But British soldiers stopped them just as they stepped in. No, those Punjabi women weren’t raped by the soldiers that day. They most likely were not raped by soldiers or policemen during the martial law regime, although there is evidence of women being verbally abused and beaten up when the police or military came to search their homes and arrest the male members of the family, of soldiers ‘exposing themselves’ when women ‘happened to stand by the window’ of their houses, of being forced to take off their veils and threatened with rape and of beatings and sexual abuse of nautch girls of Amritsar inside a police station, to mention a few.

Archival sources also tell us that no woman had been shot dead and become ‘Shaheed’ at the Jallianwala Bagh on 13 April, nor had women led any large or small public protests during the Rowlatt Satyagraha. Is that why Punjabi women are almost entirely invisible—before and after independence—in most discussions on Jallianwala Bagh, even after a century? It is as if they hadn’t suffered at all, and they had no role to play in the anti-colonial protests and the struggle for India’s independence which gathered a new momentum after the ‘Khooni Vaisakhi’—as if they hadn’t even existed!

Even if they did, they have to be unearthed from the stories of Manto and Krishan Chunder. One exception of course is Rattan Devi, who is mentioned in several places—the one who had guarded her husband Chajju Bhagat’s corpse all night in that massacred land. Her horrific experience of trying to keep dogs at bay with a stick on the night of 13 April has been frequently quoted. But what about the rest of the women?

What we haven’t remembered is that Rattan Devi and many such bereaved women had generously donated to the Jallianwala Bagh Memorial Fund. The women who couldn’t afford money had donated their children’s old clothes. Because of widespread arrests of men during the Martial Law regime, most filial responsibilities had fallen upon women. The women of Punjab had also made significant contributions to funds set up in aid of these struggling families.

The women whose husbands were deported to Andaman had donated their gold bangles to these funds. The role of Punjabi women in the post-Jallianwala Bagh independence movements—that of Bhag Devi, Phool Kaur, Pushpa Gujral, Sarala Devi Chaudhurani and many others—has been buried deep. Most people in Punjab, including women, had turned anti-imperialistic during Michael O’Dwyer’s tyrannical regime (1912– 1919).

The Ghadar Movement from 1913 also had a deep impact on them. Later, during the Rowlatt Satyagraha, women had held separate meetings within their four walls in Lahore, Amritsar, and other places. After the massacre, they could hardly mourn their dead undisturbed and unharassed. Martial Law was declared and under Brigadier General Reginald Dyer’s command, men were being tied to poles, whipped in public and sent to jail for slightest non-adherence to deeply racial orders, forced to crawl on the streets, and compelled to follow curfew-related rules. In addition to all this, British soldiers would frequently barge into houses during the absence of male members, hurl filthy abuses at the women, push and shove them and vandalise their property.

One such infamous example is from Gujranwala, where the disreputable civil servant B. S. Bosworth-Smith is reported to have forcibly uncovered the faces of several women brushing aside their veils with his stick and sworn at them. They were also threatened by Bosworth-Smith for not divulging whereabouts about their husbands with the words, “Now your skirts will be looked into by the police constables.”

After the Congress Inquiry Committee report was published in March 1920 and several depositions by women came to light, one of India’s earliest nationalist feminist leaders, Sarojini Naidu (1879–1949), took up the issue of torment and abuse of women during the martial law regime in Punjab. In protest against the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, not only did Sarojini Naidu return the ‘Kaiser-e-Hind’ medal awarded for the work she had done during the plague epidemic in India, in a fiery address in the heart of London in June 1920, she spoke about the wrongs committed against her ‘sisters’—‘the veiled women of the Punjab’ and asserted that ‘my sisters were stripped naked, they were flogged, they were outraged,’ in the name of British justice.

The India Office took note of her speech and the charges were refuted quickly with a letter from the office of the secretary of state, Lord Montagu, dismissing it all as ‘absolutely untrue.’ The Empire’s civilising mission directed against natives would have fallen flat if the charges against British soldiers and civil servants of bringing dishonour to Indian women were acknowledged. The root cause of such outrages being the ‘curse of our insignificance’, Rabindranath Tagore had pointed out in his message to the meeting in London addressed by Sarojini Naidu that: The extent and nature of the sufferings borne by the women of the Punjab at the late outrage will never fully be known and therefore will miss not merely reparation, but consolation of human sympathy.

This makes us realise more clearly than ever before that it is the curse of our insignificance which is so apt to provoke brutality in the people who have the power to rule over us and yet lack sympathetic imagination or natural bond of kinship. It is exactly this lack of sympathetic imagination that didn’t bring about an all-out condemnation by the British of General Dyer’s invention of a ‘crawling order’ to punish all ‘uncivilised’ native males for daring to physically assault one (emphasis mine) Englishwoman in a lane of Amritsar!

But why is it that violations against women have remained almost inaudible in discussions on Jallianwala Bagh in post-colonial India? Is it because women in Punjab were most likely not gang-raped and murdered by British soldiers at that time and the rest of their suffering didn’t count back then, nor later? Or is it because the magnitude of sexual violence during Partition riots, especially in Punjab was so huge, that earlier instances paled into insignificance and was consigned to oblivion? Or was it because the violations were perpetrated by the British on Indian women, and it wasn’t a communal issue between Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs, which could have been used gainfully for generating rifts between communities? The reasons are bound to be complex but whatever they may have been, these questions have been bothering me.

The suffering of the women of Punjab was a matter of concern for Gandhi and he regularly wrote about it in Young India. When he finally received permission to enter Punjab in October 1919, many meetings were separately held for women in towns that he visited, where they participated in crowds, shedding social inhibitions and defying the police. The woman who had a vital role in scouring the state and persuading women to join these meetings was Sarala Devi Chaudhurani, whose husband Rambhaj Dutt Chaudhuri (1866–1923) had been imprisoned at that time for leading the Rowlatt Protests in Lahore. Back in 1910, Sarala Devi had established ‘Bharat Stree Mahamandal’, the first national women’s organisation.

It had branches from Karachi in the west to Calcutta in the east. Reaching the women in the interiors of a devastated Punjab had been largely possible through the strength of the organisational network of Bharat Stree Mahamandal. Yet, patriarchy has so thoroughly pervaded our history and social consciousness that Sarala’s role as a leading political worker and Gandhi’s comrade in Punjab has been overshadowed by another identity. Sarala’s role as the first woman advocate of Khadi saris in 1921–1922 has also been forgotten.

For a decade or so now, she has been reduced to the ‘mystery woman’ in Gandhi’s life. While writing about Gandhi and Punjab, historians usually do not spare a single sentence on Sarala’s political contributions. It’s all about Gandhi’s personal closeness to Sarala Devi during his long stay at her house in Lahore in 1919.

In contrast, the noted literary historian of Bengal, Jogesh Chandra Bagal (1903–1972), who compiled Sarala Devi’s memoirs and other writings many years ago, wrote that, “Even without dying physically, anyone sacrificing themselves for a cause or an ideology can be termed as ‘Shaheed’. In this exact sense, Sarala Devi Chaudhurani was the first woman to become ‘Shaheed’ in Gandhi’s non-violent movement.”

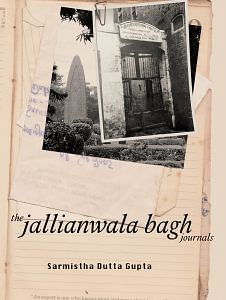

This excerpt from Sarmistha Dutta Gupta’s ‘The Jallianwala Bagh Journals’ has been published with permission from Jadavpur University Press.

This excerpt from Sarmistha Dutta Gupta’s ‘The Jallianwala Bagh Journals’ has been published with permission from Jadavpur University Press.

Ms. Dutta seems to be new age Bengali feminist associated with the woke movement. Why should everything in history must be about women? Why should women be dragged into everything?