The coming together of religion and politics is hardly new in India. Even though most popular discussions on nationalism and Hindutva tend to centre on the BJP’s electoral resurgence in 2014, the fact is that the Hindutva movement has a long lineage.

A major milestone in the journey of Hindu nationalism was, of course, the formation of the RSS in 1925, which aimed to strengthen Hindu society and unify Hindus. Hindu nationalism in its current avatar, however, has been credited to Savarkar and his maxim of ‘Hindu, Hindi, Hindustan’, which emphasized a sense of nationalism based on religious identity.

While it is widely believed that India’s post-1947 identity essentially took on a secular cast under the Congress Party, social commentators say that this isn’t necessarily true. Researchers point out that the Bharat Sadhu Samaj, for instance, was established as early as 1956, under the Congress watch, based on the belief that the ascetics would help popularize the five-year plans among the Hindus. In 1989, the Sadhu Samaj, however, turned on its parent, informally aligning itself with the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) and BJP.

Social expert and psephologist Yashwant Deshmukh goes a step further and draws our attention to the fact that ‘our habit has become that we see the history of India from 1947 and the electoral history from 1952. Whereas that’s not true. The electoral history starts from 1926. At that time, the Congress did not participate in the elections and allowed its leaders to contest elections as small groups. Even within the Congress, there appeared two factions—soft and hard factions, popularly known as Garam Dal and Naram Dal, which were different versions of secular and right-wing. By 1936, the Muslim League also emerged. That’s when politics based on religion started. The foundation of division was formed amidst this politics. Then we accepted a Muslim country, Pakistan, and a secular country, India. However, there was resentment among Hindus who remained in India after the division based on religion. This resentment grew after independence. But after Mahatma Gandhi’s death, it turned into a temporary pause. Hindus were in guilt after Gandhi’s murder. It didn’t mean that the anger that arose among the people had ended at that time. Somewhere within the Hindus of the country, there was a sense of being ignored. One could say that the issue of Hindu identity was bound to come up sooner or later, and that’s what we are witnessing nowadays. Suppressed emotions have surfaced. It could be said that the guilt of seven decades has somehow ended for Hindus,’ he opines. ‘The impact of nationalism or Hindutva always remains hidden or active in politics. We assess it differently based on different times,’ Deshmukh adds.

Noted author and columnist Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay similarly argues that there was a ‘latent sentiment in India which was unarticulated’—namely that the Muslims who desired a separate nation had been granted one, and those who had stayed must conform to the majority’s terms. This perspective, described as ‘soft Hindutva’, gained traction over time, becoming more openly expressed. ‘These sentiments, initially unarticulated, gained momentum through movements like the Ram Janmabhoomi movement and then eventually, a time came when it (the viewpoint) was considered to be not politically incorrect anymore,’ Mukhopadhyay says. Mukhopadhyay also makes an interesting point about the tricolour when he points out that the Indian tricolour had always been on display, even through the 50s, 60s and 70s. However, it was absent from Hindu right-wing organizations. ‘It was quite late when they realized that they could not make an entry into the Indian national political space unless they started appropriating the national movement and all symbols which are considered to be Indian. It is a very conscious choice which has been made slowly over the decades. Not everything has been done post 2014,’ Mukhopadhyay concludes.

Also read: Why is BJP doubling down on Hindutva? Modi-Shah have a different reading of 2024 result

Competitive Religiosity

Quoting a Supreme Court judgment, PM Modi while on a visit to Canada had stated, ‘Hindu dharam is not a religion but a way of life.’ In the current times, it sure seems like the two variants of Hindu nationalism—the BJP’s Hindutva plank and the softer variant of Hindutva or Hinduism as espoused by the other parties—have become a way of life and are here to stay.

A big case in point was seen in the BJP’s launch of its 2024 election campaign centred on nationalism and Hindutva. This initiative saw opposition parties taking a calculated political risk by abstaining from major events such as the inauguration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya. This decision sent a strong message, underscored by opinion polls, indicating potential heavy losses for the Opposition.

Amidst the fervent cries of ‘Jai Shri Ram’ and ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai ’, the BJP surged forward with determined vigour to sideline the Opposition entirely. At the same time, the Opposition countered it with their own narrative, embracing a novel interpretation of Hindutva and nationalism. They accused the BJP of excessively prioritizing religion and patriotism at the expense of other critical issues. This accusation resonated with sections of the public, leading to pockets of success.

As for the political landscape, it became a battleground of ideologies, where both sides strategically manoeuvred to sway public sentiment amidst a backdrop of nationalistic fervour and identity politics. The general election promised to be a crucial test of these competing narratives, shaping the future trajectory of Indian politics.

In conclusion, the election results have proven that the country is indeed diverse. The meanings of Hindutva or nationalism were therefore perceived differently state by state, and community by community. The election results have also shown that where the Opposition appeared confused, the BJP fell victim to overconfidence. Importantly, the results have also proven that in the coming years, all parties will need to better connect with the public on issues, which are not just related to their emotions but also to practical concerns.

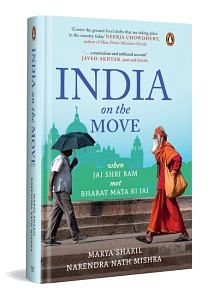

This excerpt from ‘India on the Move: When Jai Shree Ram Met Bharat Mata ki Jai’ by Marya Shakil and Narendra Nath Mishra has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘India on the Move: When Jai Shree Ram Met Bharat Mata ki Jai’ by Marya Shakil and Narendra Nath Mishra has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.