Women who were raped during the 1984 violence did not speak of it, fearing a hostile public response. For many, it was linked to their family’s honour as well. In some cases, it was the men in their families also stopped the women from filing cases, and in some, it was the mothers who did not report the rapes of their daughters, for the simple reason that nobody would want to marry into a house defiled by rape.

A woman I met during the course of my research in Tilak Vihar, introduced herself as ‘Main chaurasi ki ladki hoon. I am a girl of 1984.’ She did not wish to be named. Instead, she told me, ‘Call me a Kaur of 1984.’

When I asked about her family, she fell silent for a while. Then she said slowly, ‘Nobody likes to be associated with us, their raped daughters and sisters, if we choose to speak about our traumas.’

She went on to add, ‘Mothers tried to hide their daughters, mine also tried; she put a child in my lap and dishevelled my hair so that I would look older. But nothing helped. The men would come, discuss among themselves, choose a woman and then many like me were dragged off. Some were taken to the rooftops. Some were taken to half-burnt houses. Many were raped in the open, with other men surrounding them and watching what was happening like it was a live show. My mother and some other women tried to save me. But nothing deterred those monsters. I could see men forcing the women to leave our locality. I could see my mother standing there, from the roof where I was being raped. I began shouting, “Mummy, mainu chaddke na jaayieen. Mummy, don’t leave me here.” My mother didn’t leave without me.’

It would take the intervention of the Indian Army for some of these young women to be able to return home. Many of them were rescued from the homes of their neighbours and from nearby villages like Chilla, in east Delhi. Yet, all of them stayed silent.

‘In Trilokpuri, when women rushed out of their homes, men from the village of Chilla asked each other which one they fancied. Those women would then be kidnapped, and later, raped,’ Darshan told me. In fact, according to Darshan, there was hardly any woman in her neighbourhood who was spared the indignity. Even nine-ten-year-old girls were raped. Darshan herself witnessed many rapes.

The attackers would first empty the houses of men, burning them alive. Then, the women would be dragged inside the looted houses and gang raped. ‘The unmarried girls will have to stay unmarried all their lives if they admit that they have been raped. No one would marry such a girl.’ So, most women kept quiet. Today, most families do not openly acknowledge the fact that back then, they were worried that if they complained, the perpetrators would return to do the same things to their women again.

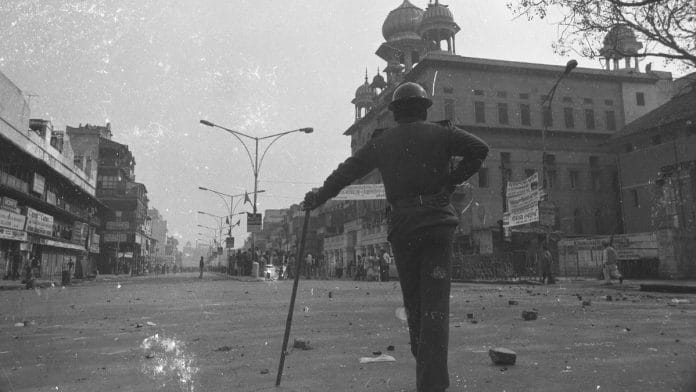

Also Read: Indira Gandhi’s assassination was a turning point for photojournalists. It made them prime targets

My first visit to Tilak Vihar, where families affected by the anti-Sikh pogrom were rehabilitated, was in December 2013, and I wasn’t prepared for how overwhelming an experience it would turn out to be. There are hundreds of families living in this densely populated colony which is also colloquially known as Widows’ Colony. While facing their own share of unique problems, most people here complain about the sordid conditions they have been living in. Yet, despite the poverty and the lack of sanitation, the one thing that stands out are their vivid accounts of losing loved ones in the massacres of 1984.

The first time I met Bhagi Kaur was at her home in Tilak Vihar. Widowed in the massacres of 1984, she is a mother of five, who lost ten other members of her family—apart from her husband—in the pogroms. We sat in her one-room home, but with three grandchildren also present in the same room, there was barely any space to move. I was direct and upfront about the nature of my visit, and I could sense that she did not really want me there. Small wonder. These were not comfortable conversations to have, neither for those who narrated their stories nor for those who listened. Nevertheless, I persisted.

When Bhagi Kaur began talking about the events of 1984, she was kind and generous with her memories, but she did not mince her words. ‘When Indira Gandhi was murdered, all of us at Trilokpuri were saddened, but nobody expected that we would be so closely associated with the assassination,’ she said. Bhagi Kaur’s two sons, Balwant and Balbir, were aged two and five in 1984, and her daughters, Anita and Pinki, were two years and six-months-old, respectively.

Along with her husband and family, Bhagi was quietly walking along a nullah on their way to the Kalyanpuri Police Station, when they were spied upon by the mob and attacked immediately. Bhagi Kaur’s husband was bludgeoned to death. ‘I had to leave my husband’s body there. I walked to Kalyanpuri and at the police station there I saw a truck full of half-burnt bodies. I spent eight months in a camp living a penurious life.’

When I asked her if the government had helped them thus far, Bhagi replied, ‘There is no meaning to any help unless the people responsible are punished. I’m sorry to say this, but nobody will understand what we are going through and no compensation can satisfy us.’

Today, amidst tears, Bhagi Kaur questions, ‘Why was this written into my fate?’

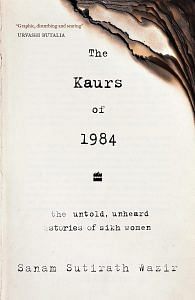

This excerpt from ‘The Kaurs of 1984: The Untold, Unheard Stories of Sikh Women’ by Sanam Sutirath Wazir has been published with permission from Harper CollinsIndia.

This excerpt from ‘The Kaurs of 1984: The Untold, Unheard Stories of Sikh Women’ by Sanam Sutirath Wazir has been published with permission from Harper CollinsIndia.