The opposition members in both the upper and lower houses across party lines expressed dissent when Minister of State for Home Affairs V.C. Shukla moved the 1967 OSA (Amendment) Bill in the upper house (the Rajya Sabha) on 24 July 1967 and in the lower house (the Lok Sabha) on 12 August 1967.

M. Ruthnaswamy’s intervention is significant in this particular parliamentary debate. He questioned the efficacy of such a bill in a democratic government. He expressed his concern about the lack of clarity on the secrecy clause and advocated that only specific cases should be treated as a secret; ‘Those acts that are prohibited must be strictly defined and delimited’ (Rajya Sabha Debates 1967: 1457–8). Ruthnaswamy’s intervention in the parliamentary debate is especially significant from the point of view of counter-ideas regarding openness in the government emerging from the opposition and within the State. He pointedly made reference to the ‘right to know’ and the ‘right to be informed’. He said, ‘After all, in a democracy one of the most important rights is the right to know, the right to be informed [my emphasis] about the affairs of the State. Therefore, the first and the most important principle governing the framing of an Official Secrets Act is that publicity should be the rule and secrecy should be the exception [my emphasis]’ (Rajya Sabha Debates 1967: 1457–8). It is important to flag here that the policy move of the speaker in the lower house in 1965 was triggered by the demand from P.K. Deo, another Lok Sabha MP from the Swatantra Party.

Ruthnaswamy and Deo’s interventions in the parliament have to be seen in the context of my argument regarding opposition politics and non-ruling parties’ demand for access to information. This is evident from the fact that both Ruthnaswamy and Deo were part of the Swatantra Party, which was founded to provide an alternative to the dominant socialist and hyper-statist ideologies of the Congress and the left parties (Erdman 1967). In this case, the ideas on openness expressed by the party members are reflective of the alternate ideology propagated by the Swatantra Party.

Also read: SC judgment on RTI Act sets a dangerously low bar for what passes muster as law of land

Another non-Congress member of the upper house, Raj Narain (Socialist Party, Uttar Pradesh), opposed the bill in no uncertain terms. Terming it a kala vidhayak or a ‘black bill’, he objected that the bill was against every democratic and parliamentary principle (Rajya Sabha Debates 1967: 1471–2). It is interesting to note that Raj Narain was part of the Janata Party government in 1977, which was formed right after the Emergency on the principles of anti-corruption, greater probity, and transparency of the State. Raj Narain defeated Indira Gandhi in the 1977 general elections on her home turf in Rae Bareli (Uttar Pradesh).

The policy moves in the parliament and opposition to the bill show early signs of an ideational counter-movement favouring openness from within the State, which intensified in later years. It is also important to point out that it emanated invariably from the opposition parties; this is evident in the profiles of the members in both the upper and the lower houses who opposed the 1967 amendment bill of the OSA. The privilege of exclusive access to official information belonging to the ruling party was at the root of such a demand by the opposition parties. I will discuss, in the following section, that the role of the opposition reached a threshold during the Emergency and the subsequent formation of the Janata Party government at the centre in 1977. This political dimension, I argue, catalysed the ideational push, which became unmistakably pronounced as the politics of the country at the centre moved from a centrist form of government to a more coalitional form.

Janata government: Decisive push for transparency and openness

This period is important from two perspectives. First, it is for the first time that a non-Congress government (in the form of an anti-Congress coalition of a number of parties) came to power at the centre. Second, this is the first instance when a government had formally expressed its political and policy intent for transparency and openness. In this sense, the Janata Party government proved to be a threshold in the ongoing ideational churning within the State; a continuity of this pattern can be seen unfolding in the post–Janata Party government.

It is in the context of two emergencies, an external emergency imposed after the 1971 Bangladesh war and the Emergency imposed on 25 June 1975, that political developments during this period are important.

Against this background, the change of guard at the centre and the coming of the new Janata Party government to power in 1977 proves to be an important juncture. For the first time, the incoming party committed formally to greater openness in government affairs in its election manifesto. In the aftermath of the Emergency, the Janata Party manifesto promised, among other things, ‘an open government’ that will not ‘misuse’ government authority and will have an open dialogue with citizens ‘at all levels and on all issues’ (quoted in Shakdher 1977: 44–5; see also Maheshwari 1981: 66).

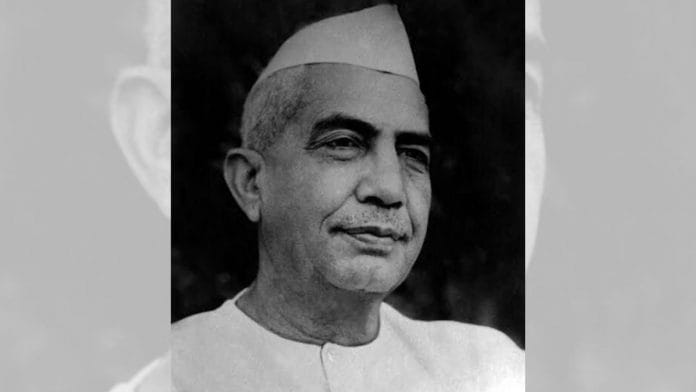

To fulfil the promise made in the manifesto, Charan Singh, the home minister in the Janata Party government, constituted a working committee in 1977 to determine whether the existing OSA could be amended to allow greater dissemination of official information in the public domain. Officials of the Cabinet Secretariat, the MHA, the Ministry of Finance, and the Ministry of Defence were the members of the newly constituted working committee. After due consideration, the committee concluded that the existing OSA should be retained without any amendment. On 4 June 1979, the government formally announced that the existing law of official secrets would not be amended but continued as it was (Noorani 1997: 115–16). Some of the reasons cited for this were that it was being done to protect the country against foreign agencies interested in procuring vital information; to preserve secrets regarding information pertinent to national security, defence, and nuclear energy; and to promote foreign relations. An exception was made with regard to news related to development work (Maheshwari 1981: 66–7; see also Noorani 1997: 115–16).

Also read: In 15 years, RTI has gone from Indian citizens’ most powerful tool to an Act on life support

In fact, on 30 August 1978, Jyotirmoy Basu (Communist Party of India-Marxist [CPI-M]) raised this issue in the lower house in his question to the minister of state for home affairs. Basu asked if the government knew of the ongoing discussion in the United Kingdom (UK) on the enactment of a law on the RTI, and wondered why, even after Independence, India still followed the outdated OSA. He asked whether the government harboured any plans to guarantee all people the right to ‘having access to all official documents’ (Lok Sabha Debates 1978). Oddly, Dhanik Lal Mandal, the minister of state for home affairs, did not mention the working group constituted to amend the OSA in his reply, but reiterated that there was no need to amend it (Lok Sabha Debates 1978; Maheshwari 1981: 68–9; Noorani 1997: 116; Viswam 1983: 183).

The Janata Party government’s commitment to an open government, as outlined in their manifesto, can also be seen in the enactment in 1977 of the Parliamentary Proceedings (Protection) Bill, which was passed to communicate parliamentary proceedings to citizens. The bill granted the media greater privilege and access of information to parliamentary proceedings (Limaye 1994: 296), and should be viewed in continuation to the 1965 ruling of the speaker of the Lok Sabha that granted parliamentarians the right to quote from confidential official documents in the parliament. The enactment of this bill was especially significant—now that the media had greater access to parliamentary proceedings, quotes from confidential official documents could indirectly find place in the public domain.

Three points emerge from the initiatives undertaken during the Janata Party regime.

First, the decision to continue with the original version of the OSA without any amendments notwithstanding, the constitution of a working committee to examine the possibility of amending the OSA in order to enable greater access of citizens to official information points towards the emerging thinking of the State on the issue of openness.

Second, the root cause of the need for openness and transparency in government affairs, felt by the political leadership at this point, is the experience of the Emergency, which entailed absolute censorship, absence of civil and political rights, and complete secrecy of official government affairs. This experience persuaded the new leadership to start thinking along the lines of participatory democracy, and government transparency and accountability. This intention is clearly outlined in the manifesto of the Janata Party, which contested the 1977 elections on the issue of corruption, and enhanced the probity of holders of public office. The promise of the manifesto was followed by the policy action of constituting the working group to amend the OSA. This intention to constitute a working committee to promote openness in government affairs by granting citizens greater access to official government information can be seen as part of a broader process that unfolded after the 1977 elections.

Also read: Modi govt was handed weak data institutions by Congress, but it ruined them further

This is reflected in the number of policy steps taken by the Janata Party government on the lines of the commitments made in its election manifesto. The initiative of the working committee to amend the OSA needs to be located within a broader policy process. Several actions point towards it, such as the lifting of the Emergency Bill in 1978 to repeal the Objectionable Matter Act, 1951, adoption of Parliamentary Proceedings (Protection Bill), 1977, 43rd Constitution Amendment Bill, 1977, to repeal the archaic 42nd Constitution Amendment (Act), 1976, and the replacement of the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA), 1971, with the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Bill, 1977 (Limaye 1994: 295–307).

Third, as discussed earlier, the push for openness from the new leadership emanated from the fact that the new coalition emerged from the conglomeration of opposition forces that had been at the receiving end of the Emergency. As the evidence demonstrates, the political opposition in the parliament was collectively against secrecy and demanded greater openness. On the other hand, the ruling party zealously deepened the norm of secrecy and protected information. The Emergency marked the acme of this tendency. The political forces that were part of the anti-Congress coalition then came together as the Janata Party. Hence, the push for openness and transparency was reflected both in political intent and policy steps towards such intent. I argue, therefore, that the role of opposition politics is a significant explanatory variable in understanding the institutional change from the norm of secrecy to openness. Institutional change was part of this churning characterized by the intensification of the norm of secrecy on the one hand and the emerging incipient ideas on openness on the other.

This excerpt from Capturing Institutional Change: The Case of the Right to Information Act in India by Himanshu Jha has been republished with permission from Oxford University Press.

This excerpt from Capturing Institutional Change: The Case of the Right to Information Act in India by Himanshu Jha has been republished with permission from Oxford University Press.

RTI act was not because ofany inner calling but because of US pressure…corruption is best buddy of indian elite…they think they can buy any thing from money…..they can buy security , big cars and even a country…