I was in my second year of law college in Lahore when Mohammad Ali Jinnah came to address the students. Habib, my Kashmiri classmate, was an active member of the Muslim League, and had arranged the function. Initially, he did not invite us, the non-Muslim students. But when he realized at the eleventh hour that the anticipated audience would not fill even a classroom, he pleaded with us to come to listen to ‘our Quaid-e-Azam’, the title which Mahatma Gandhi had bestowed on Jinnah. I told Habib that since he had not invited us, we were not planning to attend. Habib was a close friend, so I eventually capitulated and went to listen to Jinnah. The classroom remained partly empty.

This was in 1945, two years before Pakistan was constituted and before the British quit India. Jinnah went over the usual arguments that the Muslims and the Hindus were two separate nations which ate different food, wore different clothes and came from different civilizations. Therefore, the Muslims wanted a separate homeland.

After the lecture, he said he would reply to questions if we had any. I asked him two questions that in retrospect proved to be prophetic. The first was: There was already so much animosity between the Hindus and the Muslims that after the formation of Pakistan on the basis of religion, the two communities would be at each other’s throats. In reply he said that we would be the best of friends. Germany and France fought wars for hundreds of years and yet they now had good relations. My second question was: What would be the reaction of Pakistan if a third country was to attack India? He said that the Pakistani soldiers would fight shoulder to shoulder with their Indian counterparts against any invaders. ‘Remember, young man, blood is thicker than water,’ Jinnah said.

This was classic Jinnah, asserting one position, only to contradict himself a short time later. His love-hate relationship with India was visible throughout his life. He never forgot that tens of millions of Muslims lived on in India and he felt responsible for the privations they faced.

Years later, when Lal Bahadur Shastri was the home minister and I was serving as his information officer, he confided in me that had the Pakistani troops fought by the side of Indian soldiers and driven out the Dragon during the Indo-China war in 1962, it would have been difficult to say ‘no’ if Pakistan had asked for Kashmir. Would Jinnah have followed a different course of action from General Ayub Khan, Pakistan’s President in 1962? It is difficult to say. If he had, the history of relations between India and Pakistan would have been different, neighbourly and friendly.

Jinnah wanted Pakistan to be a secular state. But he could not succeed in suppressing the religious hotheads. Once Pakistan came to be established, Jinnah’s dream of having a Muslim-majority secular country went awry. Jamaat-e-Islami fanatics came to the fore and forced Pakistan to be Islamic.

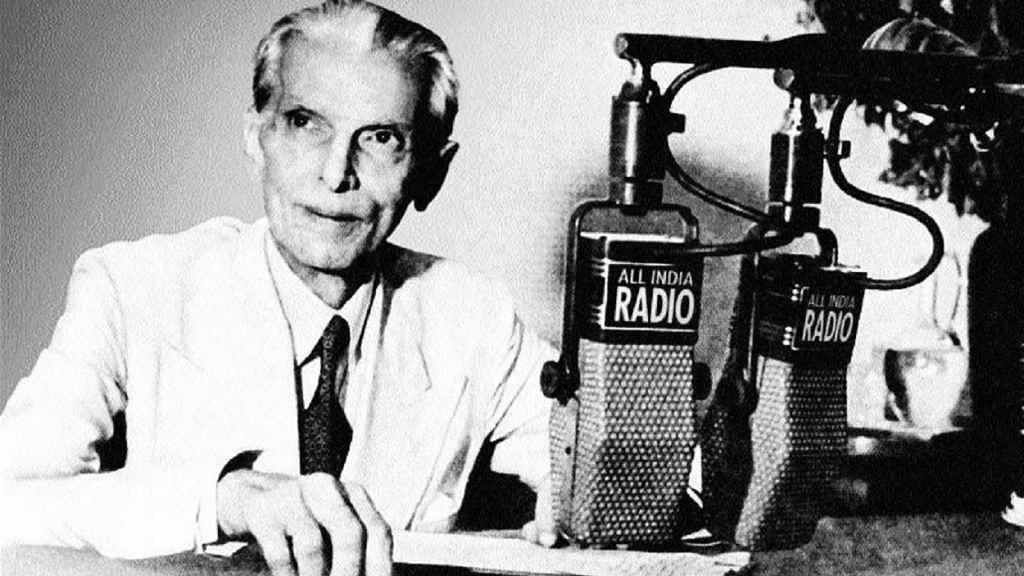

In his first speech as President of the newly formed nation, Jinnah had said:

‘I know there are people who do not quite agree with the division of India and the partition of the Punjab and Bengal. Much has been said against it, but now that it has been accepted, it is the duty of every one of us to loyally abide by it and honourably act according to the agreement which is now final and binding on all. But you must remember, as I have said, that this mighty revolution that has taken place is unprecedented. One can quite understand the feeling that exists between the two communities wherever one community is in majority and the other is in minority. But the question is, whether it was possible or practicable to act otherwise than what has been done. A division had to take place. On both sides, in Hindustan and Pakistan, there are sections of people who may not agree with it, who may not like it; but in my judgement there was no other solution, and I am sure future history will record its verdict in favour of it. And what is more, it will be proved by actual experience as we go on, that that was the only solution of India’s constitutional problem. Any idea of a united India could never have worked, and in my judgement it would have led us to terrific disaster. Maybe that view is correct; maybe it is not; that remains to be seen. All the same, in this division it was impossible to avoid the question of minorities being in one Dominion or the other.’

Jinnah’s speech could not be broadcast by the Pakistan Radio. Religious elements saw to it that it would be suppressed. Only years later, was it broadcast. There was no adverse reaction.