I was cooking one day when some students rushed in to say, ‘Vahini, your father-in-law is observing yours and Nana’s last rites out there.’

I got up and rushed to the temple to see what was happening.

What a sight it was! Mamanji [Lakshmibai’s father in-law] was chucking out all the puja vessels one by one from his upstairs room, landing them in Lord Rama’s sabha mandap. With every object he flung, he chanted, ‘My daughter-in-law is dead. This is her twelfth-day ritual. My son is dead. Here’s his tenth day ritual.’

The reason for this rage was that the puja vessels were stained. They were made of copper. I washed them with well water; I scrubbed them with wood ash; and it was the rainy season. However hard I scrubbed to make them shine, clouds would appear on them within minutes. I collected all the vessels Mamanji had thrown down and went upstairs. He had set up his gods in a corner of the school. He watched me as I came up. ‘Had you scrubbed the vessels?’

‘Yes.’

‘Swear on me.’

‘I swear on you, I had scrubbed them.’

‘You aren’t going to weep if I die of your false oath, are you?

Hold your mangalsutra in your hand and swear.’

I held my mangalsutra in my hand and swore. Why should I be scared since I was innocent?

‘Wait. I’ll call a meeting of the village women, put these vessels before them and ask them what they think. They’ll put cow dung in your mouth for lying.’

I was sure no woman was going to put any cow dung in my mouth.

‘Hold my feet and swear. Watch out. You’ll turn to ashes if you touch them.’

As I moved forward to touch his feet, he moved back, ‘Watch out. I’m telling you, you’ll burn.’

‘I don’t mind. Death at your feet might not be such a bad thing.’

Finally, I flung myself flat on the ground and held his feet tight. I did not burst into flames and die. I was very disappointed. I thought it would have been a blessing to die and be done with it. But perhaps because Mamanji’s divine powers fell short, or, quite simply, I had indeed scrubbed the vessels, I did not turn to ashes that day.

One day Mamanji took Mr Tilak aside and said, ‘Nana, you must marry another woman. I’ll get you ten girls from the Konkan.’

Mr Tilak said, ‘I have problems feeding one. What do I want with a second?’

‘Abandon her to her people.’

‘I will never do that. I don’t care how my life turns out. But I will never do something like that.’

This and the story that follows were proof of how much Mr Tilak loved me.

The water in the nearby well had dried up. There was another well in the forest. But because throngs of women went there during the day, Mamanji’s instructions to me were to fetch water at night. I was afraid of the dark. But he did not care. He said, ‘If someone comes to devour you, tell him my father-in-law is sitting in the temple. Eat him first, then come to get me.’

But Mr Tilak said, ‘Don’t worry. I’ll fetch the water.’

When night fell, I’d go out of the back door with the water pot and he would go out of the front door empty-handed. He would meet me outside and fetch water. I’d loiter around outside till he came back. Then I’d carry the water pot in. Mamanji was impressed by how confidently his daughter-in-law fetched water!

One day I was washing Mamanji’s spittoon. I felt squeamish and spat. This did not escape his sharp eyes. At night he said very sweetly to me, ‘Lakshmi, I rather like your water tumbler.

Please put that beside my bed tonight.’ So I began putting my tumbler beside his bed every night. One day the woman who came to wash vessels said to me, ‘Vahini, Dada uses your tumbler as a spittoon.’ I could not believe her. The next day the woman showed me my tumbler. That is when light dawned on me. Later I would set the same tumbler out for his puja and he would push it away.

Also read: ‘Gandhi did not stop here at all’—Why people in Dandi don’t say he walked that route

Although Mamanji tortured me in all these ways, there were two things about him which I must acknowledge. One was that he never used an obscenity when he cursed me; and two, he never touched me. In fact he would occasionally even have good things to say about me to people. One day he invited somebody for a meal. He cooked everything himself. I was amazed. Soon the guest arrived. I served him. He asked the guest, ‘How did you like the food?’ The guest said, ‘It is so good, words fail me.’ The guest was happy to have had such a good meal and I was still trying to get over my amazement.

However, this aspect of his nature did not reveal itself too often. If I asked him for something, he would fly into a rage. I was never given oil or shikakai to wash my hair. If I asked him for these things, he would say, ‘Grind grain for people and buy oil and shikakai with your earnings.’ I was reduced to cleaning my hair with mud. Halfway through my bath, he would walk off with the bucket of hot water and have a bath himself. Then I would have to complete my bath with cold water. Whenever we quarrelled over oil and shikakai, he would tell me this story:

‘Once we had run out of firewood. My wife was pregnant. Even then I made her chop wood. Why should I show concern for you? My wife never answered back. When she realized she had run out of some foodstuff, she would place the remains before me without a word. I understood that she was running out of the stuff. But today’s girls have become very arrogant. You’ll never learn how to behave with elders.’

Also read: Agyeya wanted to publish a Nehru-at-60 journal. Indian and global writers told him this

For ‘those’ three days of the month, I was left to starve. Mamanji would cook only for himself. He would cook for all of us only when Mr Tilak was around. On those days I had to sit in a dark room. I was very scared of the dark. But gradually, I lost that fear. So, in a way, the ill-treatment helped.

Mr Tilak had now made a name for himself as a poet. His reputation had reached as far as Mumbai and Pune. Although I was having a bad time, the times had turned for him. Once during that period, he was invited to Mumbai to speak. He went supposedly for eight days but did not return. Eight days went by, then ten, then fifteen. There was no sign of him and no letter from him. I began to worry. My tears would not stop. To add to that, he had told Mamanji he was going to stay at Sardar Griha in Dhobi Talao. That gave him a stick to torture me with.

‘There’s a letter from your husband today.’

‘I want to go to Mumbai.’

‘He’s found a job washing dhotis in Sardar Griha.’

‘Then I’ll hang them out to dry.’

‘He waits on people there.’

‘I’ll clear up after they are done. Just take me to Mumbai.’

‘I have no money. Fend for yourself if that’s what you want. But don’t think Mumbai is Murbad. You’ll be like an invisible pebble there.’

One day I was sobbing my heart out. Mamanji felt sorry for me. He sat down beside me. ‘Lakshmi, I have just one daughter. The other one died. You are like my second daughter. Don’t cry now. Tomorrow is the hartalika feast. Call a couple of women over in the evening. Make laddoos. I’ll give you all the ingredients.’ So he went to the market and got all the ingredients for besan laddoos. I got everything ready.

I made the laddoos. As soon as they were made, he took all but three, put them in a box, put the box in a trunk and put a lock on the trunk. The women who came got three laddoos to celebrate the feast.

On top of that, he began complaining to the women about me. ‘Lakshmi steals food,’ he said. At this, Gangabai pounced on him. ‘What does she steal according to you? Your foodstuff is all under lock and key. I suppose she eats firewood and drinks kerosene.’ He had wanted to justify his locking up the laddoos to the women. But his preamble turned the tables on him.

Also read: Ganjifa —The Persian game that became symbol of status for Indians in Mughal era

There is one other incident I must relate about the torture I suffered when Mr Tilak was away. Mamanji would collect all the neighbourhood children and tell them stories. One day when he had gone out somewhere, the children came and one of them accidentally overturned his inkpot. I had gone to visit next door. The children came running there saying: ‘Vahini, Dada’s inkpot has fallen.’ Scared out of my wits, I ran home, wiped the ink off the floor with my feet as best I could and went back next door, leaving my inky footsteps on the floor.

When Mamanji got home, he lost his temper on seeing the ink on the floor. None of the children would take the blame. He made each one of them place their feet on the footprints. None matched. Finally, he came roaring into the kitchen.

‘Come along upstairs.’

I followed his order.

‘Who spilt this ink?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Whose footprint is that? Put your foot on it. See? You spilt the ink, didn’t you?’

‘No, I didn’t.’

‘You did. It was government ink. You’ll have to compensate for the loss.’

‘How can I do that?’

‘Go grind people’s grain.’

I had gotten so used to this refrain that it no longer affected me. Nor did God ever bring me to a state where I needed to do that. Mamanji wrote two letters, one to Mr Tilak in Mumbai and the other to Govindrao Mama in Jalalpur. His letter to Mr Tilak said, ‘Your wife goes out at night and returns home at dawn. Come and take her away immediately. Or abandon her. I am not responsible for her.’

The letter to Govindrao Mama said, ‘Your son-in-law has gone completely astray. He has acquired all sorts of addictions. He has deserted his wife. He smokes ganja, charas and chandol. If you want your daughter, come and get her in three days or Iwill abandon her in some unknown place.’

Mr Tilak had full confidence in me and knew his father’s nature well. So the letter had no effect on him. But Mama and Attyabai were scared out of their wits. Attyabai said, ‘I can understand ganja and charas. But how can he smoke chandol? How does he catch it? It flies in the sky doesn’t it?’

To this Mama replied, ‘Chandol is opium.’ That scared her even more.

My father Nana was very ill at the time. There was no saying how it would turn out for him. Mama and Attyabai were in a dilemma. Should they leave him and come to their daughter’s help or stay by his side and lose the daughter?

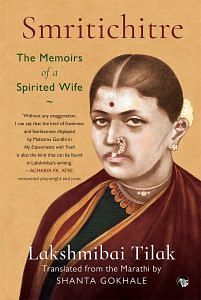

This excerpt from ‘Smritichitre: The Memoirs of Spirited Wife’ by Lakshmibai Chitre and translated by Shanta Gokhale has been published with the permission of Speaking Tiger.