Isn’t rejection heartbreaking? And what if you get rejected again and again? A pattern of rejection emerges until you are forced to find the root cause of rejection. To play the

detective. To contemplate.

But contemplation is easier said than done. What if you find something hideous hidden inside yourself that you can’t own up to? That would be bad. But it would be worse if you returned empty-handed. Like a lost child. It might seem natural to be angry and confused. To be bitter.

Being disabled sometimes makes it easy for you to lie to yourself. Why were you rejected for that job? Because disability. Why don’t you have good friends? Because disability. Why does the other person not find you attractive? Because, ahem, disability.

It becomes a cheat code. A one-size answer that fits everything. A lie that you start believing. Of course, there are things that go wrong in your life because of disability. You are on the margins. Humiliation becomes an everyday exercise due to a lack of accessibility and social understanding. But you can’t blame everything on disability.

Personally, I have faced these questions over and over again. And sometimes, have blamed it all on disability. It’s an easy solution. But in the last few years, ever since I moved towards acceptance of who I am and how my life is, I have found myself meditating over these things in a more analytical way. Being satisfied with what I am doing and the close group of friends I have has definitely made me more assured in life.

But in all this, the thing that has haunted me most is the idea of love and attraction. I have written about this before, but one thing I haven’t talked about is the innate queerness of my disability.

For a long time, I went along with the straight but queer gig. What is that? Let me try and explain. My body is disabled. It is fat. It is curved. It is wearing a diaper. It is on antibiotics. It is in pain. People like me will never fit into the ideal of what the perfect body is and what it is supposed to be. There are many things my body won’t be able to do. There are also things that bodies like mine can do but which are frowned upon by society.

Like, have lots of sex. In fact, most of the sexual aspects of a disabled body are looked at with suspicion. There is a history of disabled women being treated in a horrible way

because of their sexuality and are often discouraged from becoming a mother.

In the heteronormative world, this preference for a normal body is also combined with social customs such as marriage, the idea of family and monogamy. So, basically, you have to fit into all these categories to find some level of acceptance in society. For generations, disabled people have adopted this route and found acceptance within their families and society. And even these choices have been brave and inspiring.

But what if you don’t want to fit in? Or you can’t fit in? What if your idea of sex is different from the conventional norms of heteronormative sex. Sex, at least the kind that is approved by society, is procreational sex. But what if bodies can’t do that? For example, when I have UTI (urinary tract infection, which is my chronic illness), I have to find different ways of giving and experiencing pleasure in bed. There are many others who can’t even move and don’t have caregivers or therapists who can act as facilitators. Where do we go in the heteronormative world? Do we have to live as second-grade citizens, waiting for the pity of the able-bodied world? Or do we lose our right to desire and be desired?

For me, being queer started not as an identity but as a political position, finding solidarity in people like me who have been mocked and marginalized because of their bodies and who they are. And I would rather find myself among people who accept me for who I am. It is not surprising that it is also a stage of life when I am surrounded by wonderful queer friends, who are all fighting and living on their own terms. When you live on the margins, being out there, living your life becomes an act of resilience. And that brings us together more than anything.

But queerness isn’t just a political position, is it? It is practice. And sometimes it’s a difficult practice made worse by the heteronormative boundaries that you build around yourself over the years. I remember when my classmates used to make fun of me. For being fat. They used to often ask questions about my masculinity. How will you do it with a big paunch? Will you be able to find the gate to the cave? They would all laugh unanimously.

The lack of imagination was surprising. If I can go back in time, I would like to give them a glimpse of my disabled body having all kinds of sex. After navigating the straight and the queer world for long enough, though, I am neither surprised by the lack of imagination nor

tempted to give a glimpse of my sexual acts to any of those men. It’s not their fault entirely. Don’t all the relatives advise brides and grooms to lose weight so that they can have sex? What is their imagination of a sexual act if not intercourse in the missionary position?

My first steps into being a queer person were not as easy as it seems. Just be yourself, they say. But what if your sense of self is confused and full of inhibitions? It didn’t help that there were people standing everywhere, gatekeeping the holy world of queerness. Who are you into? Are you gay? Are you bi? Are you trans? The questions weren’t nasty, though they always left me nervous. I don’t know, was my polite answer. And, as if to add an explainer, I would say, you know, because of chronic UTI, it’s a problem, I can’t decide. Again, hiding behind disability.

Only a half-lie because my UTI directly influenced my sexual life, although it could never influence my desires. Still, I was hiding.

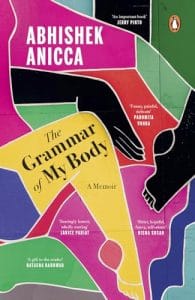

This excerpt from The Grammar of My Body by Abhishek Anicca has been published with permission from Penguin.

This excerpt from The Grammar of My Body by Abhishek Anicca has been published with permission from Penguin.