Widows in the West were expected to dress entirely in black, even including their umbrellas. This tradition carried on in rural areas until the late twentieth century, with many widows faithfully mourning their husbands until they themselves passed away. Wealthy women who became widowed tended to reflect current fashions in their mourning dresses, while less-well-off women sewed their own from cheap cotton dyed Black.

During an initial period of intense mourning with strict rules, widows wore a mourning veil that covered their head and face. Thanks to this opaque heavy black veil (made from stiff crêpe material in the nineteenth century), combined with a full black mourning dress, widows could go about their day-to-day business in public spaces without creating any awkward embarrassment. Unfortunately, however, the black dye used proved to be so toxic that widows would develop breathing problems, leading one doctor to state in an 1898 copy of the Dietetic and Hygienic Gazette that ‘Many a woman has ended up in a coffin through the wearing of crêpe’.

The second mourning period would last between two and two-and-a-half years, during which time a widow would still be expected to wear a veil, but she could have this hanging off her back and would be able to freely look around. This lighter form of mourning allowed for the previously strict rules to be eased.

In addition to black, colours such as grey and mauve were allowed, and one could also switch to fabrics such as matt silk, possibly with a light motif. In Western lighter mourning phases, jewellery could also be worn again, although these should be modest. Sparkling jewels and shiny fabrics were not allowed to be taken out of the closet until people were completely out of Mourning.

In the nineteenth century, those not fully up to date with what a widow ought to wear would consult magazines such as Revue de la Mode (France) and World of Fashion (United Kingdom). Even handkerchiefs were given black edging to meet these mourning trends, as we can see from the extract from Dutch magazine De Gracieuse at the start of this chapter. European mourning fashion was conceived at the royal court and imitated by tailors for the upper classes, before being adopted by ordinary citizens towards the end of the eighteenth century.

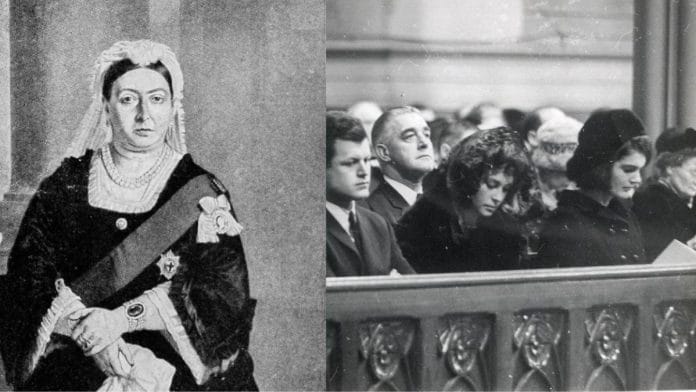

During her lifetime, Queen Victoria was the widow-par-excellence when it came to life-long mourning attire. Following the death of her husband,Prince Albert, in 1861, she spent forty years wearing only black until her death in 1901, occasionally topped with a white veil or headdress, as can be seen in her portrait by Carl Rudolph Sohn. This dedication to her late husband had an enormous influence on the mourning practices of women in Britain and elsewhere in the Western world.

Also read: Not 1952, India’s electoral history started before Independence

The established mourning colour of black was in turn taken by British colonists to Australia, as can be seen in the photo from the photo album of an early British settler family. This widow is dressed entirely in black, including a short cape, gloves and a cap with a see-through veil in the same colour. In her black-gloved right hand she holds the black-bordered white envelope containing the death announcement of her husband’s passing.

At a time when black was considered de rigueur for mourning dress in Europe, queens and consorts would sometimes choose to wear white instead, a practice which started in France in the sixteenth century. White symbolised the hope and expectation that the deceased husband would be reborn. After the death of her husband Prince Henry in 1934, white was also the choice of Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands for her mourning dress.

Until well into the twentieth century, women still wore black veils or hats with dark veils in stately western mourning ceremonies. Gradually, that western face covering was halved or further shortened to a narrow veil. Upon returning from the ceremony, the veil would be pulled back to reveal the grieving widow beneath: a sign that she could now show her face to the world again.

A noted example of this was Jacqueline Kennedy at the funeral of her husband, President John F. Kennedy; during the funeral she kept to the old tradition of covering her face with a mourning veil, and only once the ceremony was over did she allow everyone to see her face once more.

Rules about how widows should dress can vary, even within a country, culture or religion. In Islam, the shroud for the corpse is always white, the same as the clothing worn by pilgrims when on Hajj in Mecca, but Muslim widows have not always worn white. In North Africa, traditional mourning attire is often white, but in Egypt both Muslim and Coptic women in cities choose to wear black. Some widows wear black for the rest of their lives, while in rural areas they often wear white for this same reason. Imams affirm that there is no set mourning colour for widows in Islam, other than a preference for a calming colour. Black creates a more serious impression, while white exudes calm, as long as it is not a brilliant white.

As old rituals lessen in intensity, some traditions carry on out of a sense ‘how things ought to be’ but without the urgency they once had. Western widows no longer feel the need to hide behind a dark veil for protection. Those who want to cry in front of others can do so without embarrassment, although some are still ashamed of doing it. The contemporary explanation is that the black veil allows the sorrowful widow to weep unseen, but the original protective function of a widow’s veil has now been forgotten.

This excerpt from Mineke Schipper’s ‘Widows: A Global History’ has been published with the permission of Speaking Tiger Books.

This excerpt from Mineke Schipper’s ‘Widows: A Global History’ has been published with the permission of Speaking Tiger Books.