The turn towards the body in the dialectic of mind and body presents a broad field of investigation for performance studies. The anti-theatrical turn in theories of performance liberates the body from its art-bound anatomy to a structure of feeling. Bodies in this context might become a lens for or a methodology of cognition. In this trajectory of embodying knowledge, it is crucial to ask what constitutes the event of circus.

The emergence of ‘print capitalism’ (Anderson 39) as a crucial factor in the nineteenth and early-twentieth century discursive formations of colonial identity in India, marks a movement towards the textualisation of the visual—inscriptions of ways of seeing. If we delve deeper into this argument, it invokes two critical positions: (a) the form of circus and its staging of the colony; (b) colonial discourse formation through the textual circulation of the empire and the extent to which it mediated the performative dimensions of circus. The former position is elucidated by Paul Bouissac:

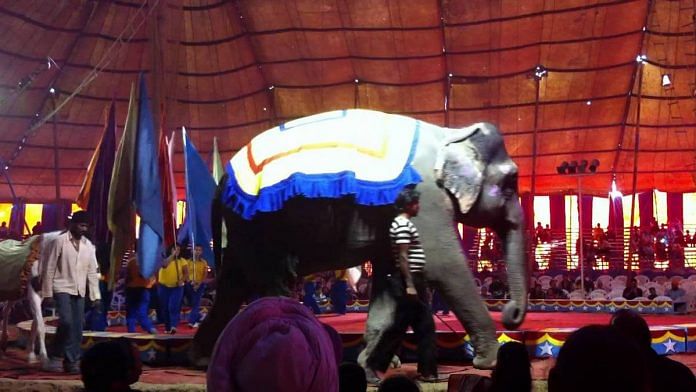

Circus performances, though, are essentially visual and acoustic events. “Writing the circus” cannot merely consist of producing reliable verbal narratives of circus acts. Even if these translations into a written language can achieve some degree of completeness when they are supported by exhaustive analyzes of the components and dynamic of the multimodal processes of these acts, the visual information will always be missing. (Circus as Multimodal Discourse 29)

Within the field of circus studies, situating circus in colonial Bengal as an embodied space goes beyond considerations of circus as an anticolonial, nationalistic engagement of the body. This chapter opens up ways of looking at the form of the travelling circus beyond its structural and organisational apparatuses and seeks to engage with its visceral dimensions in a capillary critique of the cultural techniques of improved corporeality as a discourse. In this regard, the ideologues of colonial modernity and its framing of bodies is fraught with tensions that are marked in an affective reading of circus in colonial Bengal as a space of intersection between the textual and the bodily aspects of its physical culture.

While the nature of corporeality in a performative context imbibes phenomenological attributes to a considerable extent, it is significant to consider how bodies engender performance spaces along historical, gendered and biopolitical axes of power. Circus in colonial Bengal can be conceptualised as an area that aptly elucidates the nodal points of corporeality and the discourses around it, through a deep and affective reading of the textual and visceral dimensions of circus as an embodied space. This could give rise to fresh debates around existing circus historiography.

Also read: India does not believe in conflict between ecology and economy, says PM

Narrativising bodies under the big top

The performative dimension of circus as an event is marked by physicality in both its personal and semiotic spheres. The semiotic bodies of the circus thus present themselves as addenda or extensions of the material bodies in the context of the spectacle of performance—‘the tactility of vision is an addendum to the visible space’ (Merleau-Ponty 134).

The various spectral movements of the acrobats on triple bars, horizontal bars and trapeze as well as the freak shows, all add to the kinesthetics of circus as an event and an experience of the liminal staging of itself as an embodied experience. While circus’s performative visuality evades strict codes of theoretical and conceptual categories—phenomenology, neurocognitive science, semiotics, of how the idea of the moving body may be conceived within the framework of performance theory—writings on circus and its associated physical cultures have been in increased circulation since the 1850s.

These moving and malleable bodies are thus stretched and contorted, not just in the arena, but also beyond it into text through memoirs; travel books; newspaper reports; quasi-historical accounts; biographies; narrative accounts of circus enthusiasts; and fiction. The mode of circulation of physical culture, not only in practice but also in the imaginative and fictional currency of these literary sources, becomes a necessary engagement in understanding how the body intersected with popular discourse. The loss of the visual in the modality of liveness, not as a phenomenal reality but as an ontological state, becomes necessary to engage with while thinking about circus through/in the written form. A dominant narrativisation of body practices in nineteenth and early-twentieth century Bengal aimed at the deification of certain forms into a ‘nationalist’ strain—a form that was predominantly a middle-class Hindu one.

The trope of the brave, masculine, heroic male body stood at fictional loggerheads with the popular notion amidst Europeans of Bengalis as a lazy and effeminate race. This strategic narrativisation forms one of the intersections between circus in text and performance, marking the metonymic abstractions that cultural forms take. Abaninda Krishna Basu presents a specimen of the European view of the Bengali character by referring to an entry in Mr. Haber’s (a British colonial officer) journal: ‘I have understood from many quarters that the Bengalees are regarded as the greatest cowards in India.’ This also finds classic expression in the following observation by Macaulay:

The physical organization of the Bengali is feeble even to effeminacy. He lives in a constant vapour bath. His pursuits are sedentary, his limbs delicate, his movements languid. During many ages he has been trampled upon by men of bolder and more hardy breeds. Courage, independence, veracity, are qualities to which his constitution and his situation are equally unfavourable. (25–26)

In this regard it is of historical and political significance to note as a counterpoint to the alleged enfeeblement of the Bengali race as an intrinsic trait, that in 1700, Calcutta had 1200 English men and women, 460 of whom died in one hot summer. This was largely due to a policy of pauperisation monitored by a court of British directors where poor, diseased and vagrant bodies were isolated, marking a systemic abjection in colonial politics. The management of bodies as resources of utility through labour was controlled through the Vagrancy Act introduced in 1870.

The organisation of labour exchanges in workhouses in Bombay during the nineteenth century point to poor conditions of work and wages. It was through these workhouses that marginal Europeans were employed, but who could not compete with the rate of cheap labour that was available among the natives. This led to a growing discourse around vagrant Europeans—some of whom had been in India for a long time and those who had been born here—as corruptible, degenerate, feeble and morally unscrupulous due to the influence of the native races and climate.

This excerpt from Ambika Aiyadurai, Arka Chattopadhyay and Nishaant Choksi’s ‘Ecological Entanglements: Affect, Embodiment and Ethics of Care’ has been published with permission from Orient BlackSwan.

This excerpt from Ambika Aiyadurai, Arka Chattopadhyay and Nishaant Choksi’s ‘Ecological Entanglements: Affect, Embodiment and Ethics of Care’ has been published with permission from Orient BlackSwan.