Millennials, or even their moms, may never have heard of ‘Bleeding Madras’. But this was the catchy name of a fabric that caught on with the world’s trendies in the Swinging Sixties. It had a gobsmacking journey from a south Indian village to salons worldwide, not unlike our protagonist’s own trajectory. Like him, the tale is an example of the SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis long before it became a management mantra. But the story goes beyond mere similarities. Captain Nair is the story.

His marriage to Leela had made him change tack from managing wartime rations to selling textiles. Remember? Along with his daughter’s hand, A.K. Nair had handed over the sales agency of his Rajarajeshwari Weaving Mills to his son-in-law. It was in this capacity that Krishnan first displayed his marketing chops. He based himself in Bombay, targeting the crammed, chaotic lanes of the historic Mulji Jaitha market, considered to be Asia’s largest textile trading hub. He would periodically return to Kannur to collect more samples.

His skills managed to earn him a fair amount. Not princely, but more than his army pay. It enabled him to give a fairly good life to his beloved Leela and their two sons, Vivek, born on 3 January 1952, and Dinesh, who emerged on Christmas Eve three years later. But the commission didn’t always come in time, even though it was from his father-in-law’s mill.

So here’s a little story. Leela was pregnant a third time and decided to have the baby in Bombay instead of at her parental home. The delayed commission meant there was no money for the nursing home. Too proud to ask his father-in-law, Krishnan went to a customer he was quite close to. R.K. Seth readily tided him over. The infant girl didn’t survive beyond a few months, claimed by smallpox. Krishnan kept his indebtedness to Seth in his memory, and returned the favour two decades later, when the cloth merchant fell into dire straits. By then, the modest sales agent had become India’s biggest exporter of ready-to-wear to the US.

His experience in selling handloom and power loom fabric made Krishnan realise the importance and potential of India’s ancient and once globally coveted weaving tradition, prompting him to suggest a board for the promotion of handloom to Morarji Desai, then the chief minister of Bombay.

This led to, first, the All India Handicrafts Board and, much later, a similar body for handlooms, both of which would be taken to unprecedented heights by Pupul Jayakar, the czarina of rural arts, crafts and textiles. For Krishnan, from there it was a logical step to take ‘Made in India’ to the world.

Also read: Benares brocades wove Hindu-Muslim peace for centuries. But those old ways changed

In 1958, he had joined an offi cial trade mission to suss out the US market and decide a strategy to captivate this Consumer No. 1. The homework had already been done when the influential American textile importer William Jacobson visited Bombay the same year and called on the textiles commissioner, T. Swaminathan, ICS. The commissioner directed him to Krishnan Nair. Weighing the options, our man selected and showed the buyer a lightweight cotton fabric with bright, tartan-like checks, worn by the Kalahasti women of Tamil Nadu

Expertly fingering the fabric, Jacobson asked what was special about it. Krishnan suavely rolled out its USPs. It was woven using 60-count yarn for the warp and 40-count yarn for the weft. Its vegetable dyes used laterite stone, indigo blue, turmeric and local sesame seed oil, all of which made the fabric exude a distinctive scent. He added that it was already a hit in West Africa where it was being used for making flamboyant gowns for weddings and other celebratory occasions.

Krishnan then produced his weakness-as-strength trump card. The fabric had to be washed gently and separately in fresh cold water; with each wash, the colour would ‘bleed’– thus creating a different kind of check. The possibility of a ‘new’ garment with each wash excited Jacobson, and the two struck a dollar-a-yard deal. An immediate shipment of 10,000 yards was ordered. Brooks Brothers scooped up the entire lot, and tailored it into sporty jackets, shirts and shorts under its iconic menswear label.

The shelves were stripped within a week. Laidback post–World War II baby boomers couldn’t have enough of ‘Bleeding Madras’. But this did not happen before a crucial omission left many faces red with anger and embarrassment. In the ‘excitement’ over his discovery, Jacobson had ‘forgotten’ to mention the all-important ‘care’ instructions to Brooks Brothers, who therefore didn’t mention them on the tags of the finished products. All hell broke loose because customers found that their colours would ‘bleed’ not only into the fabric’s own checks but also run into the other clothes which were unwittingly washed along with them.

Legal notices flew thick and fast, suing against the non-fast colours. Krishnan’s expensive lawyers washed him clean of the whole caboodle because the fault was clearly Jacobson’s, who admitted as such. The matter ended with the American importer paying damages to Brooks Brothers and a stroke of adroit marketing. Th at ‘weakness into strength’ formula

was flaunted by Madison Avenue maven David Ogilvy, who came up with the tag line ‘Guaranteed to Bleed’.

Also read: Not Quite ‘Madrasi’: ‘Coromandel’ offers a panoramic view of south Indian history

Naturally, all the other prêt labels cottoned on, and made it part of their summer collections. Seventeen magazines provided the ultimate endorsement with an eight-page spread on ‘Bleeding Madras – the miracle handwoven fabric from India’. Clever Krishnan would extol the qualities of this textile but never let on the details of its production. He knew the dangers, even in the times when GI stood for ‘government issue’ or ‘general issue’ and not for the complexities of the ‘geographical indication’ tag or, for that matter, the ‘glycemic index’ of food.

Here’s a prescript. Nair, Jacobson and Brooks Brothers may have created this American fashion sensation of the 1960s, but the lowercase use of ‘madras’ as a generic name for a light, cotton fabric had a much older provenance. Th ough less storied than the Spice Route, Europe’s maritime nations had also coveted India’s fabled textiles. Not just the ‘woven air’ Dacca muslin, but the hardier calico. The Dutch came for it first, but like for everything else, the East India Company bested the rest. The firm had been set up in 1599 on London’s Leadenhall Street, and from an office just ‘five windows wide’ would command an empire as political as it was mercantile. As William Dalrymple chronicles in The Anarchy, “It accomplished a work such as in the whole history of the human race no other trading Company ever attempted, and such as none, surely, is likely to attempt in the years to come.”

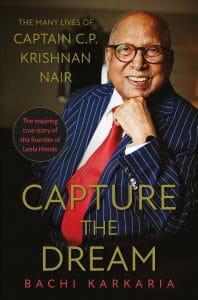

This excerpt from ‘Capture the Dream’ by Bachi Karkaria has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books.

This excerpt from ‘Capture the Dream’ by Bachi Karkaria has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books.