Known as the father of folk renaissance in India, Jamini Roy was an acclaimed artist renowned for his use of bright colours, bold and sweeping brushstrokes and two-dimensional renditions of human, animal and mythological forms, influenced by traditional Bengali folk motifs and Kalighat paintings.

Born in Beliatore, West Bengal, Roy grew up in Bankura, which had rich traditions of terracotta wooden toy making and folk paintings. These art forms, as well as his upbringing in an idyllic village, played an important role in shaping Roy’s artistic sensibilities. In 1903, at the age of sixteen, Roy enrolled at the Government School of Art, Kolkata, where he was introduced to European art pedagogy and its modes, styles and aesthetic values. He was particularly inspired by Western Modernism and the Post-Impressionist work of Vincent van Gogh. After graduating with a fine arts diploma in 1908, Roy began painting portraits in the academic style on commission till the early 1920s.

From 1910–20, Roy worked at the Indian Society of Oriental Art, which resulted in him moving away from his previous, largely Orientalist style of painting. Consequently, he began deepening his familiarity with the folk pat vocabulary and studying the pictorial traditions of the *Kalighat pat as well as the paintings of Sunayani Devi. Dissatisfied with the limitations of his Eurocentric academic training and the Revivalist movement in Bengal, he began moving away from both modes by the mid-1920s, with the aim of defining an alternative ‘modern’ Indian art.

His early works to this end resulted in depictions of village life and popular Bengali myths and folklore. He was also influenced by the forms and iconographies of the Kalighat and Santhal pats, patachitras, clay figurines and the temple reliefs of Vishnupur. However, Roy rejected the influences of the Kalighat style due to the increased efflux of traditional painters to urban market centres (mostly Kolkata) and the resultant alienation of the art from its traditional roots to serve urban tastes.

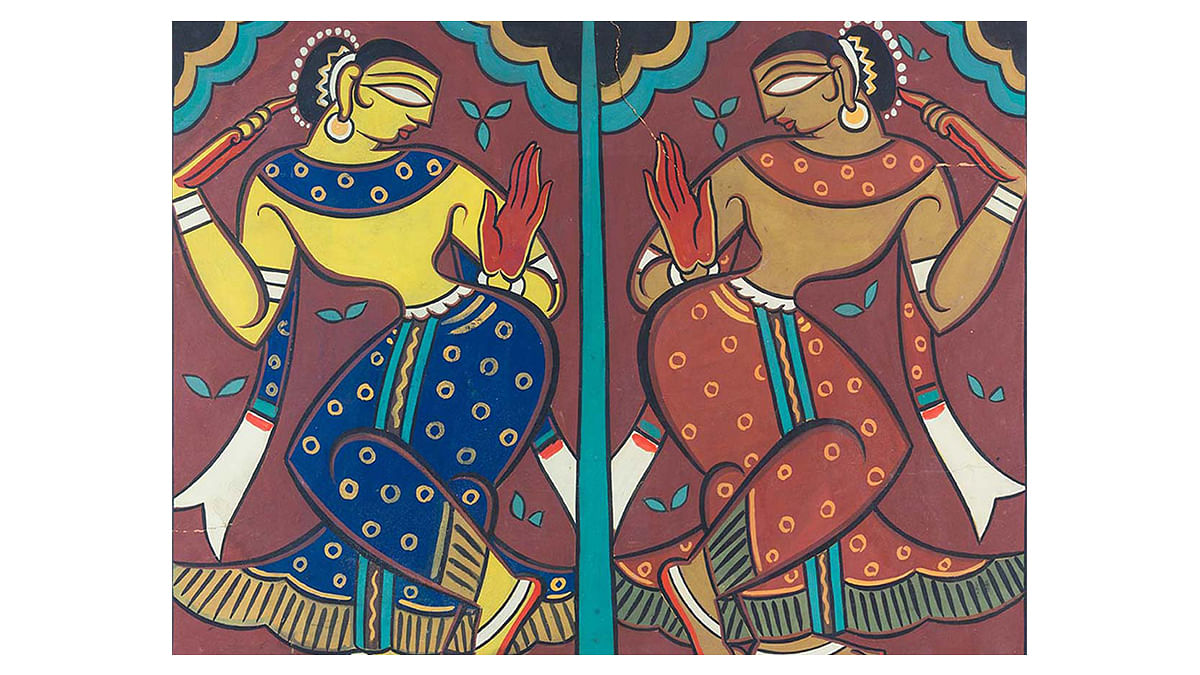

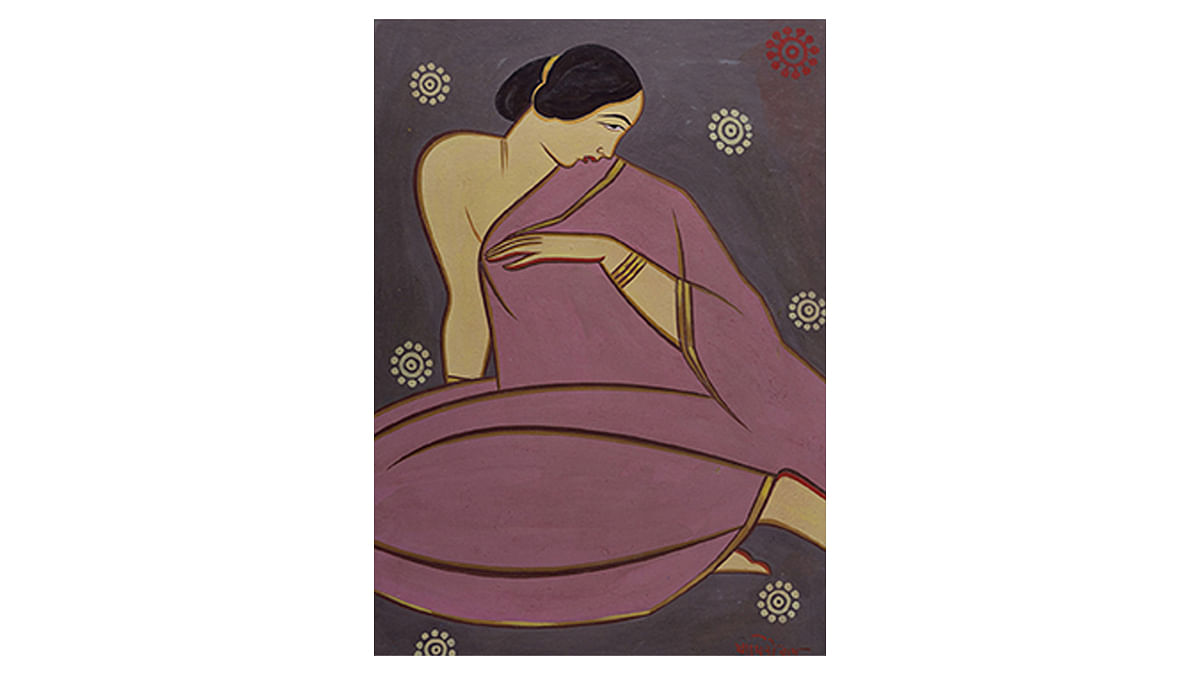

Consequently, Roy returned to villages in West Bengal, especially Beliatore, multiple times, modifying his style and method of working, such as abandoning oil paints for earth colours that he mixed himself. His work became informed by the recurring motif of vernacular art that he encountered during this period, resulting in the development of a style centred on heavy lines, stylised forms and flat colour application in primary colours made from natural and local materials (such as rock dust, tamarind seeds, mercury powder).

Also read: Haseenain-e-Lucknow—a photographic record of tawaifs and what it tells us about Awadh

Roy’s work was instrumental in defining a unique identity for Indian art in postcolonial India, foregrounding the indigenous cultural ethos as opposed to socio-cultural and political issues such as war, famine and poverty that were being examined by his contemporaries. His early works, created post-1930s, featured religious icons from Hindu epics and mythology, Biblical themes and women.

His figures were characterised by exaggerated almond-shaped eyes and expressionless faces. In keeping with the timeless and ‘author-less’ social and community traditions of folk art, Roy neither named nor dated his works; most of his paintings have been titled posthumously. He also created numerous works throughout the 1950s that he often gave away.

However, some critics have argued that Roy’s appropriation of folk motifs puts into question the uniqueness of his work, while others allege that the simplified structural pattern of his work was largely driven by his desire to mass-produce paintings for financial gains. He has also been criticised for the idealisation of his artistic subjects, their formulaic depiction, and the alienation of his works from the social, political and cultural realities of his time.

Roy’s work has been exhibited widely, including at the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), New Delhi; the Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi; and the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. His works are in the collections of NGMA and the Lalit Kala Akademi. He was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1955. He was also one of the nine artists whose works were declared national treasures under the Antiquities and Art Treasures Act, 1972.

Roy died in Kolkata in 1972.

This article is taken from the MAP Academy‘s Encyclopedia of Art with permission.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit, open-access educational platform committed to building equitable resources for the study of art histories from South Asia. Through its freely available digital offerings—Encyclopedia of Art, Online Courses, and Stories—it encourages knowledge-building and engagement with the visual arts of the region.