For centuries tigers were very numerous and considered dangerous vermin. The French seventeenth-century traveller Thevenot wrote: ‘Though the Road (between Agra and Delhi) I have been speaking of be tolerable, yet it hath many inconveniencies. One may meet with Tygres, Panthers and Lions upon it…’ This was no exaggeration. Johnson recalled how early in the nineteenth century, British officers were allotted money to keep open a road and to cut the jungle back on either side for fifty yards ‘without which, it would have been dangerous in the extreme for any small body of people to have traversed that road, the tigers being so numerous’. The East India Company (EIC) introduced rewards for killing tigers in the eighteenth century and there were also rewards for killing panthers and leopards which lasted into the twentieth century. One of the most celebrated victims of a tiger attack was the son of General Sir Hector Munro who in 1792 was carried off while picnicking with friends. Williamson wrote in 1808 of the dangers to travellers of tigers, adding that:

The death of a tiger is a matter of too much importance to be treated with indifference. The Honourable East India Company, with a view to prevent interruption to the common course of business, and to remove any obstacle to general and safe communication, bestow a donation of ten rupees, equal to twenty-five shillings, for every tiger killed within their provinces. The Europeans at the several stations situated where the depredations of tigers are frequent, generally double the reward.

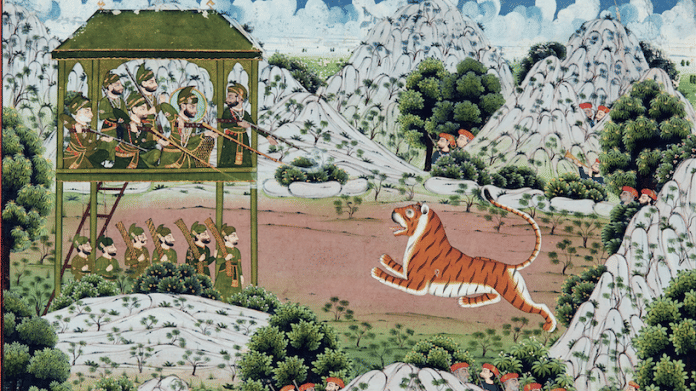

In the second half of the nineteenth century it was estimated that tigers killed 1,600 people a year in India and considerable numbers of cattle. Jim Corbett mentions a man-eating tiger that had killed about 200 people in Nepal before moving to Kumaon where it killed a further 234 people, one a week over four years, before it was shot. The removal of tigers was a duty as well as a privilege of rank which Indian princes and British administrators across India took on with delight tempered with respect. The usual practice was to sit up over the corpse in a machan and shoot the tiger or leopard when it returned to its kill. The perils of travel in India were described by the experienced Hugo James who wrote in 1854: ‘In traversing a district covered with jungle, travellers should be careful to have fire-arms by them; in fact, no one ought to move in India without pistols. If men do not attack you, possibly a tiger or some other denizen of the forest will suddenly pay you an unwelcome visit.’

Also read: Do-piyaza, blood-spitting paan, camels — The ‘bizarre’ food of Mughals in Western travelogues

Nicholson, an ICS man, made it a rule that if ever a tiger was seen he was to be informed at once. Public business was at once abandoned for the hunt, common practice across India, but Nicholson’s chosen means of killing tigers was unique. He liked to ride his terrified horse in circles ever closer to the tiger until he could lean from the saddle and kill it with a sword. The God-fearing Nicholson who ruled with Bible and sword was one of the bravest of the brave, so much admired that some Indians worshipped him as a god. He was so troubled by these disciples wanting to touch him that he had to issue orders that anyone who did so would be flogged which greatly added to his allure. The tiger was regarded with grim admiration, hunting a game where the best men matched their wits and courage with that of their quarry. In Bengal, a collector at Tipperah was killed by a tiger, which he thought he had shot dead the previous day.Villagers argued that once reduced to reasonable numbers the damage tigers did to their cattle was more than compensated for by the tigers keeping down wild pigs which otherwise ruined their crops. However coexisting with tigers brought problems as events in the late nineteenth century at a remote railway station demonstrate:

The smaller railway stations only boast as a rule two baboos – the station master and the telegraph clerk….a telegram was received by the traffic superintendent at Calcutta, from the baboo at some distant little station.

‘Calcutta Mail due, tiger at points. What shall do? Waiting orders.’

Then a minute later came a frantic appeal – ‘Tiger in station! Baboo on roof! Wire instructions!’

In 1899 Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Adams claimed that ‘the tiger is still to be found in many parts of Marwar and Sirohi although he is yearly becoming scarcer, and must shortly follow the fate of the lion and cease to belong to the fauna of these jungles.46 In the Maharaja of Jodhpur’s copy of Aflalo’s The Sportsman’s Book of India, published in 1904, was written: ‘In Kathiawar, the last home of the Indian lion, which, but for the nawabs of Joonaghur, would now be extinct, the tiger is absolutely unknown, as it likewise is in Bikaner, Jodhpore and other more or less desert tracts.’ The word ‘Jodhpore’ is firmly underlined and in the margin Maharaja Umaid Singhji has written a crisp ‘No!’.

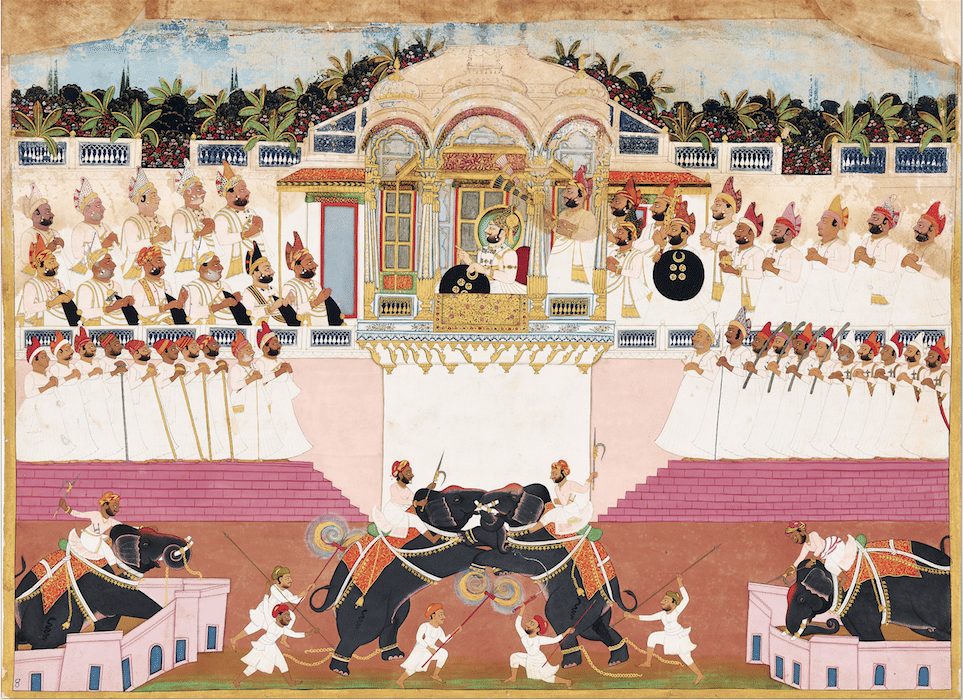

In the north from the Terai down to the Bramaputra, jungle often consisted of enormous stretches of giant reeds, in some places eighteen-feet high, intersected by streams and quicksand where nothing could be achieved on foot. Local guides were essential and the probable success of the sportsman was directly related to the number of elephants he had in his party. A party of half-a-dozen guns would require about fifty howdah and pad elephants, the former for riding and the latter for carrying supplies. These could not be simply hired but had to be begged or borrowed and much depended on contacts and importance. In 1876, when the Prince of Wales was the guest of the Nepalese prime minister in the Terai, the latter assembled 500 elephants to ensure good sport. A line would be formed, the pad elephants interspersed with the howdah elephants, which would advance, beating the jungle. This sort of shooting required neither woodcraft nor even fine shooting as one often fired at a patch of moving grass. Men took their wives, cold drinks, sunshades and dressed without concern for camouflage. Sir Montagu Gerard, with his experience of tackling tigers on foot, was unimpressed, remarking that ‘there is not the smallest risk incurred to any save possibly the mahouts or people on the pad elephants’, describing it as ‘altogether a thoroughly Oriental rather than English form of sport’ though decidedly interesting because of the great variety of game that might be flushed from cover.

Also read: Yes, she did — New findings show prehistoric women hunted too

In contrast to this sybaritic form of hunting, in many parts of India the tiger was pursued on foot so physical fitness was essential. A two-month shooting leave involved walking three or four hundred miles as reports arrived of tigers killing cattle, forcing the hunter to zig-zag across the region, moving camp ten or a dozen miles several times a week. In central and southern India, except in reserves, there was often only a pair of tigers or perhaps a family of three, four or five tigers in an area of two or three hundred square miles. Good local shikaris would know where there was water where tigers might lie up in hot weather in March, April and May when water is scarce. At this season the gun barrel could become so hot as to blister the hand. An experienced man knew his bearer might not be close at hand in the jungle with the .577, which was heavy to carry on a long march on a hot day: many carried a .500 as a second gun on a sling over the left shoulder, butt first, in case they suddenly needed it. A large mature tiger weighed between 400 and 450 pounds and in scrubland could charge at up to twenty paces a second. In the Indian jungle game is seldom seen beyond fifty or sixty yards and a tiger’s brain, the optimum target, is a mere two-inch square. If the tiger was wounded it became the personal responsibility of the hunter to track and kill it, the most dangerous game in the world. Often the hunter became the hunted. The hunter needed iron nerves and the ability to read the warning bell of a sambur, the bark of a karkar or muntjac, the alarm call of monkeys and birds to tell him where the tiger was. Corbett describes tracking a tiger through thick scrub where he noted that the grass on which the tiger had briefly lain was just springing back up, which he judged meant that he was within a minute of it without knowing precisely where it was. For this a gun was needed to suit the game being hunted and the strength of the user. In India a heavy rifle with good stopping power was preferred for big game while in Africa lighter rifles were used. One cannot better the advice given by Gerard, a tiger hunter of great experience, who suggested that the useful all-round weapon in 1904 was something between the .500 Express of the past and the modern .265 Mannlicher.

It is a very different story indeed when you are selecting a rifle intended specifically for tiger shooting under all conditions, one whose stopping power you must, when following up a wounded beast on foot, entrust your life.

This excerpt from The Maharaja of Jodhpur’s Guns has been published with special permission from Niyogi Books.

So bad of them we have to save animals

ANIMALS KILL FOR NEED

HUMAN KILL FOR GREED